This is the Nov. 20 edition of “The Tea, Spilled by Morning Joe” newsletter. Subscribe here to get it delivered straight to your inbox Monday through Friday.

Bad news comes in waves, especially for presidents who cut themselves off from the outside world.

Nancy Pelosi had to tell Joe Biden that he couldn’t get reelected. She also gently let him know that his advisers were misleading him.

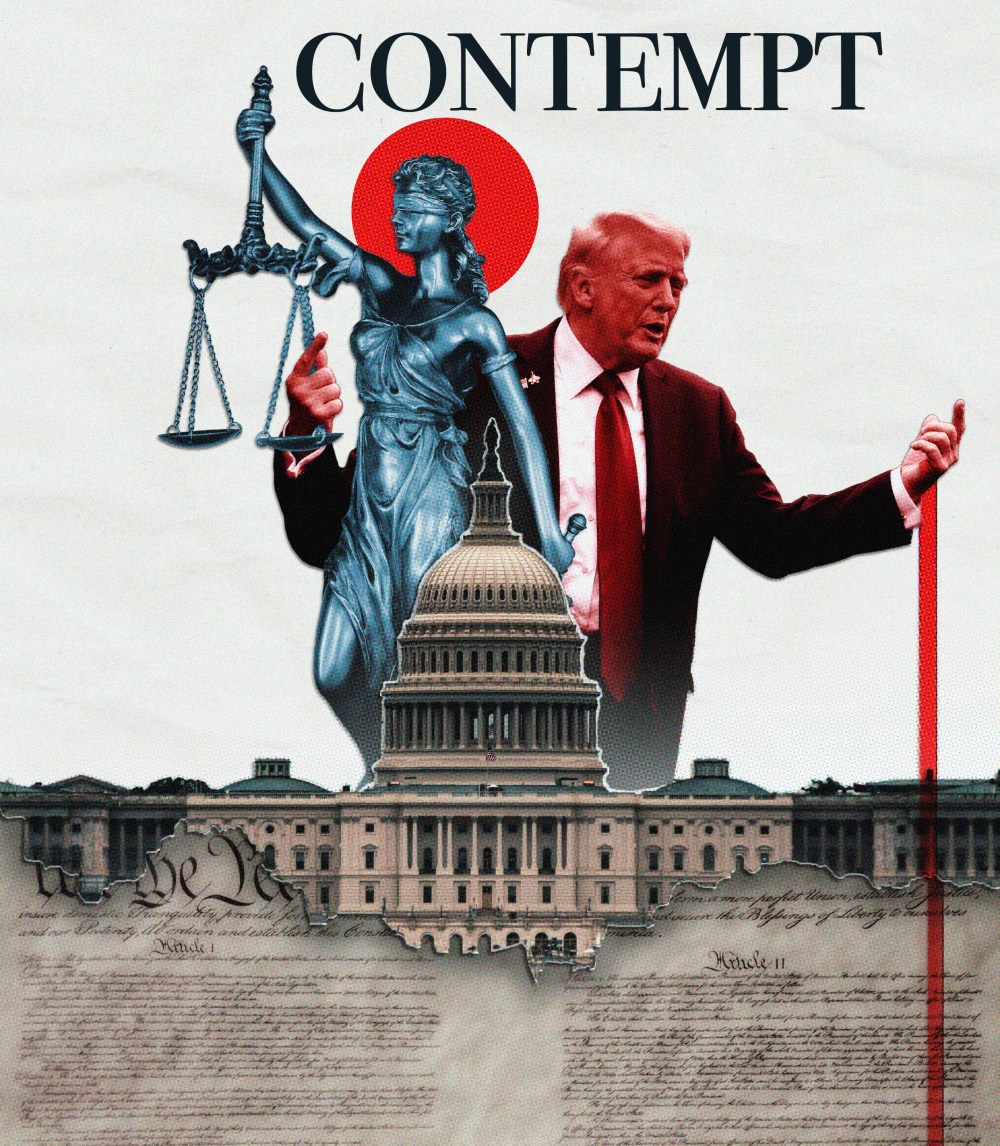

Now, a growing number of Republicans on Capitol Hill fear that Donald Trump is becoming more like the predecessor he loathes.

As Jonathan Lemire reports for “Morning Joe,” Trump has no one inside or outside the White House who can tell him the truth. Most dissenting voices from his first term were cast aside long ago and exiled to the political wilderness. Others now face prosecution from Trump’s Department of Justice.

And yet, judging from recent courtroom events, the politically persecuted appear to be faring far better than the DOJ lawyers trying to put them in jail.

I’ve never read a story quite like the one that broke last night on the remarkable events unfolding in an Alexandria, Virginia, courtroom. Judge Michael Nachmanoff eviscerated government lawyers nervously standing before him yesterday in the federal courthouse building where former FBI Director James Comey is set to be tried. The judge legally deboned them. Will they next be disbarred by their peers? Maybe they should place a call to Rudy Giuliani.

In today’s The Tea, Spilled by Morning Joe: A mix of Pulitzer Prize-winning historians on their favorite presidential subjects, Eugene Robinson’s searing take on the White House’s negligence on climate change, 5 Questions with Donny Deutsch, the 4 Dumbest DOJ Moves This Week, and one final thought from Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy.

Enjoy!

So Ms. Halligan was the stalking horse, or to use a different word — a puppet — for the president?

Reimagining Mount Rushmore: ‘It’s Character That Matters Most’

Pulitzer Prize-winning presidential historians Jon Meacham and Doris Kearns Goodwin joined us on the “Morning Joe” set to choose which American commanders in chief they believe deserve a place on a reimagined Mount Rushmore. After debating superagent Ari Emanuel on his “Rushmore” podcast, the two revered scholars sat down to discuss their favorite presidential subjects and what sets them apart from their peers.

JS: Doris, when you write a presidential biography, you say you live with that president for the years required to finish the particular project. Who is the most remarkable president you lived with during your work?

DKG: Abraham Lincoln. It was not just what he did — saving the union, winning the war and emancipating the slaves. It was also who he was as a man. When Leo Tolstoy said Lincoln was the greatest historical figure, the Russian novelist said, “It’s character that matters the most.” It was the moral fiber of Lincoln’s being that set him apart.

When I began working on Lincoln, I visited the home of the great Lincoln historian David Herbert Donald. I admitted that I was scared. “How am I going to do this? So many other books have been written about him.”

Donald said, “You will never regret living with him. You will feel like you’re a better person at the end of that time.”

I told Steven Spielberg the same when he started his movie on Lincoln, and I said the same to Daniel Day-Lewis. And in time, they both felt something special living with this remarkable man. There was something about his empathy and compassion, his kindness and his willingness to forgive people who had hurt him. He possessed an ambition that was centered on something so much larger than himself.

JS: Jon, you also lived with Lincoln for a long time, as you did with [Thomas] Jefferson and Andrew Jackson. Compare them.

JM: What holds Jefferson and Lincoln together is a reverence for, and an investment in, the power of the English language to transform lives and to elevate events — instead of tearing down political rivals and institutions. These leaders took great care with what they wrote and what they said to push us on this journey toward a more perfect union. That devotion to language is essential. In some ways, Jefferson and Lincoln were always in conversation together across time.

JS: In what ways?

JM: Lincoln called the founders men of iron, and in the first speech he gave in Springfield in the late 1830s, young Lincoln spoke to America’s founding generation — how many from that time are dying and how it is now his generation’s duty to keep their flame alive.

JS: What part of the founders’ legacy did Lincoln find most vital?

JM: Lincoln believed his generation needed to carry the founders’ legacy forward because it was a legacy founded around something so much more significant than land or property. It was a legacy built on an idea.

JS: What about Andrew Jackson?

JM: Jackson was far from perfect, but what makes him so interesting is he didn’t get the chance to accomplish everything he wanted, everything that he had articulated. We learn more from sinners than saints, and that made Jackson fascinating.

JS: Doris, Lincoln took Jefferson’s sentence from the Declaration of Independence into battle because it was the guarantee of equality that slaveholders feared the most. They were horrified that Lincoln was holding up the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution to say, “These two documents live as one.” And it was this slaveholder’s declaration from 1776 — that all men are created equal — that struck fear in the slaveholders and secessionists that Lincoln was battling.

DKG: It was the anniversary of the Gettysburg Address yesterday, and that’s really where we take the Declaration of Independence and make it, as Lincoln does, the founding idea for America — not just the Constitution, but Jefferson’s Declaration.

Words matter. Words can hurt, words can divide, words can unite, words can inspire. That’s why it’s important to remember history and the power of words. And that’s why it’s so great that we’re still talking about these ideas today.

AT THE BELÉM SUMMIT, CHINA TAKES THE STAGE — AND THE CAKE

A guest essay by Eugene Robinson, MS NOW political analyst and contributing writer for The Atlantic

Ignoring a problem doesn’t make it go away. The U.N. is currently holding its annual climate change summit, this year in Belém, the Brazilian metropolis at the mouth of the Amazon River. Virtually every nation on Earth is represented — except the United States, thanks to Donald Trump’s pigheaded denial of global warming.

As with much of Trump’s foreign policy, the absence of U.S. leadership leaves the door open for Chinese leadership. And in Belém, Xi Jinping’s representatives are having their cake and eating it, too. So much cake.

China is by far the world’s biggest emitter of heat-trapping carbon dioxide. Only the United States has the economic leverage to pressure the Chinese into making a faster transition to clean energy — but Trump is busy canceling wind-power projects and pushing energy companies to drill for oil the world doesn’t need. Meanwhile, thanks largely to market forces, the energy transition is indeed taking place, no matter what Trump thinks — and China is the nation producing most of the solar panels, wind turbines and other technology needed for the switch.

Wang Yi, a leader of the Chinese delegation in Belém, told The Guardian that China would love to cut its carbon emissions more sharply, but only “in cooperation with other countries. We don’t want to take the lead alone. We need comprehensive leadership.”