As Arnulfo Bazán-Carrillo and his 16-year-old son, Arnoldo, pulled out of a Houston McDonald’s in Arnulfo’s white van, a group of unmarked vehicles pulled up behind them. Then came the flash of lights.

They assumed it was the police. “We went into a parking lot and we just pulled [over],” Arnoldo told MS NOW.

The two quickly sensed, though, that this was not a typical traffic stop. Men jumped out of cars with guns drawn and masks over their faces. Arnoldo said he saw no police department or agency insignia. He heard no commands or officers identifying who they were. “Masked,” he said. “Like, nothing on their chest. Nothing.”

Arnoldo insists the men did not identify themselves or so much as say, “You are under arrest.”

“They started banging our windows and they tried to open the door, and when they pointed the gun at us, it’s when me and my dad were like, ‘What’s going on?’” Arnoldo remembered.

Fearing for their lives, his father made the fateful decision to drive away. “We didn’t know what was happening,” Arnoldo said. “My dad just backed up trying to protect me.”

As they raced down streets on the west side of one of the nation’s biggest cities, Arnoldo started filming, and a fear he had long suppressed came to the surface: His father one day being taken by immigration authorities.

“Oh, no. No, f–––, no!” Arnoldo can be heard shouting in the seven-minute video he shared with MS NOW. “It’s immigration, it’s immigration!”

What happened next was a stark example of emboldened immigration enforcement officers leveraging high-risk tactics designed for the desert, not major metro areas. All to arrest someone with no felony record.

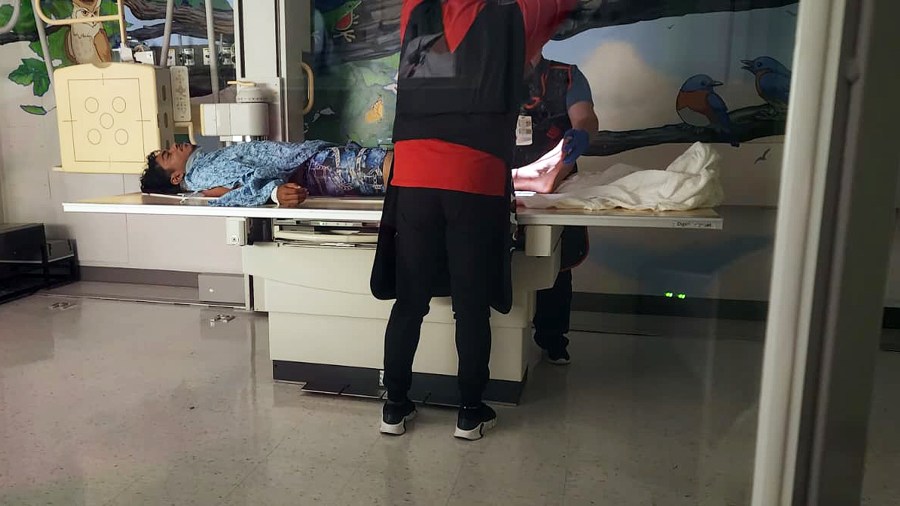

It ended with a father and his U.S. citizen children separated; a teenager receiving morphine in a children’s trauma unit, where a nurse reported he had been assaulted; and — in a twist that local authorities are now investigating as a potential crime — his seized cell phone sold for cash in a Walmart parking lot.

A special morning cut short

It was rare for Arnulfo to have a morning slow enough to eat breakfast with his son.

He fled violence and instability in Mexico in the 1990s and moved to the U.S. illegally, forging a life in Houston that left little time for mornings at the kitchen table. As a chef, he often worked seven days a week to support his three daughters and Arnoldo. He bought his boy his first soccer ball when he was 4, and often took on double shifts to cover the cost of his new cleats or the eye-popping fees for private soccer clubs.

So when Arnoldo, who’d grown into a soccer standout and football player at Hastings High School, asked his father if he would treat him to McDonald’s before they drove to school on Oct. 23, Arnulfo acquiesced.

He didn’t know it would be the last meal they would share together, at least for a long time.

The Department of Homeland Security told MS NOW that Arnulfo “recklessly rammed his car into a federal law enforcement vehicle and fled violating numerous traffic laws and endangering the lives of everyone in the local community, including his son’s.”

But in Arnoldo’s video, the agents can be seen ramming Arnulfo’s truck at least four times.

And Arnoldo can be heard begging his father, “Let’s go home, let’s go home.”

Once an agency that focused its most aggressive tactics and covert operations on drug dealers, sexual predators and terrorists, DHS has been transformed by President Donald Trump’s goal of deporting a million people a year.

And the Bazán family’s hometown consistently ranks at or close to the top of the list for the nation’s most deportations. In March 2025, for example, Harris County, which surrounds Houston, saw more immigrants ordered removed than any other county in the U.S.

Former DHS leaders and Immigration and Customs Enforcement prosecutors, as well as highly trained agents, tell MS NOW that much of the cultural shift has been driven by one key policy change: The Border Patrol, once generally restricted to zones within 100 miles of the Northern or Southern border, is now taking a leading role in deportation operations, bringing cartel-land tools into the interior.

As reports emerged of frustration in the White House with the pace of deportations, the Trump administration announced late last year — less than a week after the Bazáns were detained — that roughly half of the 25 regional ICE field office leaders would be reassigned and replaced with current or retired Border Patrol officers. Jenn Budd, a former senior Border Patrol officer who left in the early 2000s after a career in the rugged hills and deep canyons of San Diego, dubbed the shift “Borderpatrolification.”

For Budd, what happened to the Bazáns sounded all too familiar.

“That’s how we behave on the border,” said Budd, who authored a book critical of her experience with the agency. “We rip people from their cars, we ram them with our vehicles, and then say they tried to ram us.”

John Sandweg, former ICE acting director under the Obama administration, says the kind of surprise confrontations and collisions that the public now sees on a regular basis were once reserved for traffickers and shootouts with cartels.

“We’re seeing the results of this: Car chases, car crashes, broken windows, you know, strong-arming, you know, go right to Level 3,” Sandweg said. “The highest level of force from the very beginning, rather than work progressively.”

J.A. Gaitan, a retired specialized Border Patrol agent based in Houston, welcomes the agency’s bigger role and freer hand. While he doesn’t support the current politicization of the job, he says Border Patrol agents have sought more opportunity and collaboration since he first joined in the late ’90s. “They have a lot more liberty now. A lot more liberty. It’s long overdue,” he told MS NOW.

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem and other administration officials have called out sharp increases in reports of assaults against immigration enforcement officers since the government began deploying thousands of them in “surges” in mostly Democratic-led cities.

Sandweg shares Noem’s concern that agents are facing heightened risks of doxxing, harassment and public attacks. But in his view, the administration’s policies are like gasoline to fire.

“You don’t need to wear a mask when you’re arresting bad guys on the streets,” Sandweg said. “The public celebrates you. You’re not the villain in that case. And unfortunately, I think this administration’s policies have made ICE, have made them villains.”

A teen choked and beaten

Arnoldo continued to film as his father stopped the van and ran into a Restaurant Depot, where, the family says, he knew some of the workers and believed he would be safe. He barely made it inside before officers caught up to him.

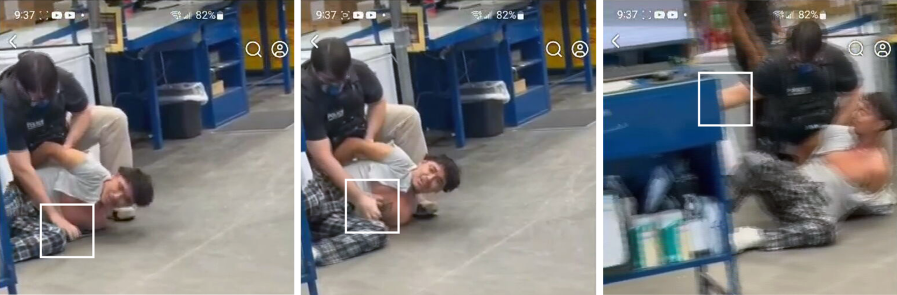

MS NOW has reviewed three videos showing what happened to the father and son once they were inside. While the videos are chaotic and fast-paced, much of what can be seen conflicts with the public account provided by DHS.

A group of agents, some wearing masks and carrying guns, followed Arnulfo Bazán inside the business and pinned him to the ground. In one of the videos, three agents are wearing tactical vests that read “Police” and one agent’s vest is marked “DEA.”

DHS Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin told MS NOW that allegations that federal officers assaulted Arnulfo and Arnoldo are “FALSE.” She described Arnulfo Bazán-Carillo as “a 49-year-old criminal illegal alien from Mexico” and said he entered the U.S. six times illegally and has a conviction for driving under the influence. MS NOW found that it was a decade-old misdemeanor.

McLaughlin did not respond to MS NOW’s question about whether agents knew any of this information before attempting to detain the father and son.

Arnoldo says he was watching from the car as three men kicked and punched his father down on the ground. “I was like, ‘I’m not gonna let that happen,’” Arnoldo told MS NOW. “I’m pretty sure everybody would react the same way if they saw their dad getting beat down.”

Arnoldo followed his father and was quickly tackled by two other officers. “My heart kind of broke in that moment when I saw him screaming for help,” said Arnoldo. “I tried my hardest to stay cool, but my emotions got to me.”

In one video recorded by a bystander and obtained by MS NOW, Arnoldo can be heard pleading with the agents to stop. “Y’all trying to kill me out here, man. Y’all crazy,” he’s heard saying. He screams and swears at them repeatedly.

In that video, an agent is also seen pressing a knee into Arnoldo’s back, while another restrains him using a head hold. Arnoldo cries out, struggling to speak, telling the agents he is underage and was born in the U.S. Arnoldo told MS NOW the agent tightened his grip. In the video, the agent can be heard telling him, “You’re done.”

In another bystander video, Arnoldo can be heard telling the agents holding him to the ground that he has recorded their actions and will try to sue them. Shortly after, one agent takes his phone and passes it to the agent wearing the DEA vest, who then walks Arnoldo out of the store carrying his iPhone and AirPods.

It would take four days, a visit to a tech-for-cash kiosk in a Walmart parking lot and a police report before he saw the phone again.

DHS told MS NOW that the Bazáns resisted arrest, and that Arnoldo “elbowed a law enforcement officer in the face,” though they “graciously chose not to press charges.” MS NOW has been unable to confirm Arnoldo struck an officer with his elbow in any of the existing videos, and Arnoldo denies it. Videos and photos show Arnoldo’s shirt ripped, and visible cuts and bruising across the teen’s upper body.

As he sat in the back of their car, Arnoldo says the agents used racial slurs, calling Arnulfo a “border hopper,” “beaner,” “dumbass” and “criminal.” At one point, he recalls an agent calling him a “son of an alien.”

In all of this time, Arnoldo says, agents still did not identify themselves or produce a warrant.

Agents drove Arnoldo and Arnulfo — handcuffed, frightened and disoriented — to their family home. Arnoldo was released. His father was not.

“I gave him one last hug, but it kind of broke me,” Arnoldo said. His father was still in handcuffs and could not hug him back.

Arnoldo’s oldest sister, Maria Bazán, recalls stepping out of the family’s house to find chaos. There was Arnoldo, dazed, his eyes completely dilated as he struggled to breathe and speak. “I started screaming, but it wasn’t me,” Maria recalled. “It was like something inside of me, like a motherly instinct.”

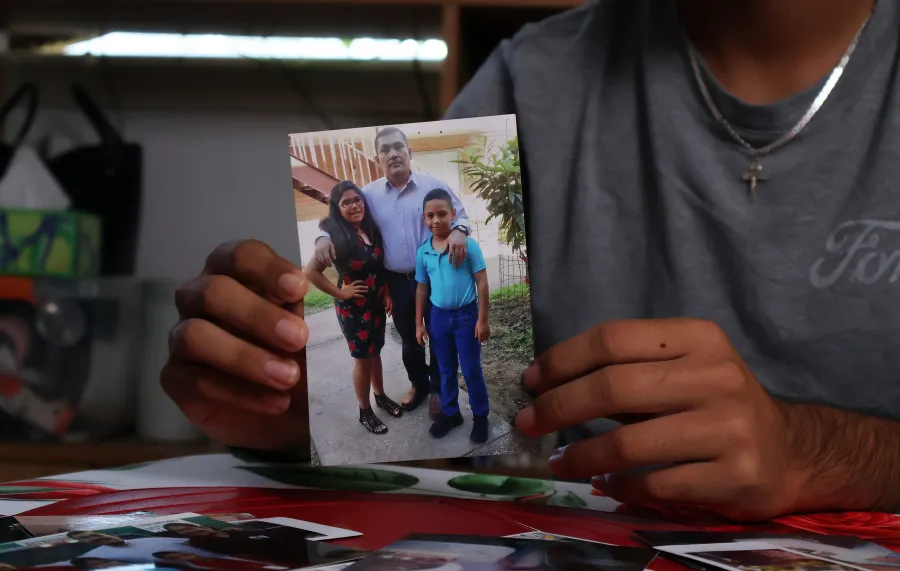

Maria explained to her little brother that they needed to go to the hospital. Before he agreed to get in the car with his sister, Arnoldo stumbled into his bedroom and grabbed an old photograph with his father and sister Selena, taken on the way to church. He held on to it the entire ride.

As Maria and Arnoldo traveled to Texas Children’s Hospital, the agents drove their father to the Montgomery Processing Center, an immigration detention facility in Conroe, Texas. Arnulfo says that once he got there, officials told him that if he did not sign papers agreeing to his deportation, agents would pursue charges against his son and “send him to juvie.”