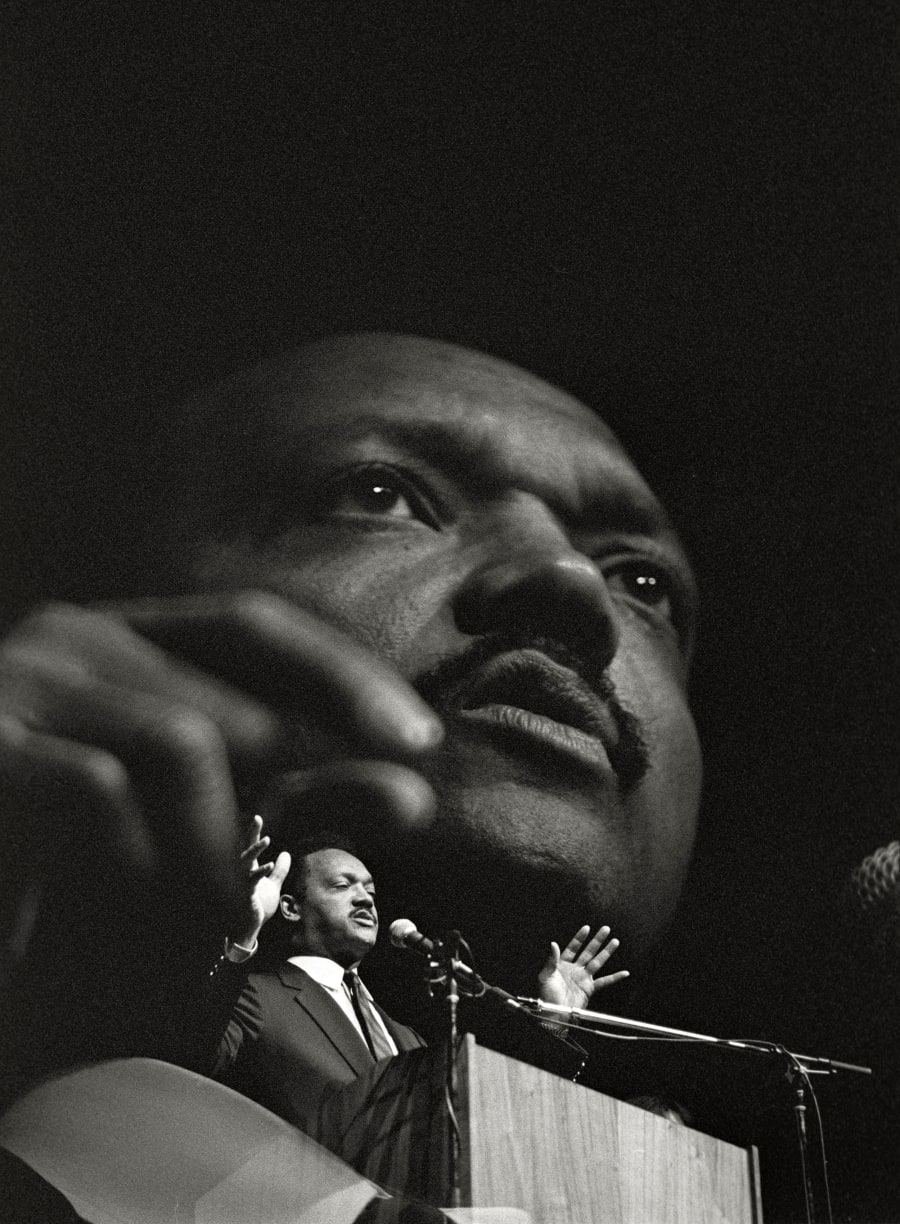

My earliest memory of Jesse Jackson dates to 1984. I was 5 years old and saw him on television during the Democratic primary. I heard the announcer say “reverend” and remember thinking that Jackson looked like other men I knew but that something about what I was seeing felt different.

I was too young then to consider that millions of people could have been equally captivated by this charismatic, sharply dressed man with a big voice and a presence that seemed to come through the television screen. In that moment, I could not appreciate that Jackson was having a similar impact on other Black boys — and people across America. But now I understand that as history considers Jackson’s legacy, whatever controversies it fairly records should not diminish this conclusion:

Jackson honored the responsibility of telling the truth about the pain of Black America — and forced members of the Black elite and the white political establishment to listen even when they preferred not to hear.

Jackson was an American hero. His voice bridged a generational gap between the toil of societal agitators, as did his mentor, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and he cemented acceptance of Black voices at the highest levels of democratic institutions.

Throughout his life, Jackson honored the responsibility of telling the truth about the pain of Black America — and forced members of the Black elite and the white political establishment to listen even when they preferred not to hear. His was a voice borne out of a demand for America to settle the debt of inequality magnified during the Civil Rights era. Jackson understood the complexity of that debt and saw it partly as retroactive repayment for an economy that Black labor had helped build.

Jackson lived in an America that would have been content to believe that such policy gains as affirmative action, the 1965 Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 signaled that all was well. (Of course, we are fighting to preserve what remains of these advances five decades later.) Instead of abetting that complacency, Jackson remained a thorn in society’s side for decades, challenging America to deliver on its promise of access, inclusion, opportunity and protection to all. Although the Civil Rights policies of the 1960s bore fruit in the enlargement of a Black middle class during the late 1970s and early 1980s, significant numbers of Blacks still experienced poverty. Jackson refused to let that go overlooked, even as many preferred to focus on the success of upwardly mobile Blacks.

For his dedication, Jackson faced endless attempts throughout his career by both centrists and conservatives to paint him as too race-driven and too radical, and tacit suggestions that Black America might benefit from supporting a more docile, reasonable voice. Undeterred, Jackson continued advocating for social justice and economic equality through efforts such as Operation Breadbasket and groups such as the Rainbow PUSH Coalition.

His brilliant political organizing, voter registration and mobilization efforts in Black communities would be felt for generations. It seemed wholly implausible in the 1980s that someone with such a meager political resume could stir so many within the Democratic electorate for not one but two presidential bids. Especially not a Black man who was not independently wealthy and had no major donors to fund his campaign. Yet Jackson constructed a blueprint for voter registration and mobilization through his fraternity, Omega Psi Phi, that he then replicated through the other historically Black fraternity and sororities within the National Pan-Hellenic Council (also known as the Divine Nine). The result harnessed the Black electorate’s political power in a way not seen since Reconstruction.

Jackson’s second-place finish in the 1988 Democratic primary did not secure the nomination but succeeded in legitimizing the concerns of Black America as part of Democrats’ core platform. Critically, the political machine Jackson engineered in the 1980s paved the road for a number of Black successes, including the election of Wilson Goode as mayor of Philadelphia, David Dinkins as New York’s first Black mayor and Kurt Schmoke as mayor of Baltimore. Arguably, Jackson’s speech at the 1984 Democratic National Convention created space for another skilled Black orator and presidential hopeful also from Chicago, Barack Obama, to take the DNC stage 20 years later and deliver a speech that would prove to be his national debut. But the beneficiaries are not limited to candidates — or to men. Donna Brazile gained experience as part of Jackson’s campaigns. Kamala Harris’s “secret weapon” support from her college sorority in 2024 was a direct nod to Jackson’s voter organization efforts.

As a member of Omega Psi Phi, I saw the apparatus Jackson built utilized through the fraternity’s nationwide voter registration and mobilization program. Conversation around Black male voter engagement and participation rates in Democratic politics should acknowledge that Jackson’s vision included Black men taking part in national conversations on economic opportunity, education and employment.

One such important conversation was around the 1994 crime bill. Jackson warned of potentially devastating effects, cautioning that an overemphasis on punishment instead of prevention and a failure to focus on rehabilitation and community resources would have a disproportionate impact on Black men and incarceration rates. The timing of the bill, as a response to the crack cocaine epidemic that ravaged urban America, ultimately pitted Jackson’s critique against elected leaders divided on how to address the crime in their districts. Members of the Congressional Black Caucus, including then-Rep. Charles Rangel and Rep. Kwesi Mfume, D-Md., bristled at Jackson’s disparagement, arguing that he did not live in their districts and was “playing politics with crime” while failing to offer viable alternatives. Then-President Bill Clinton and then-Sen. Joe Biden, who co-authored the bill, were among those who said Jackson had it wrong and generally suggested that his position was soft on crime.