As a professor of philosophy and ethics, I am more accustomed to reading the news than being a part of it. But many media outlets have reported this week on a directive I was given to excise Plato lessons from a course syllabus. I offer this to provide insight into my experiences at Texas A&M both recently and more broadly.

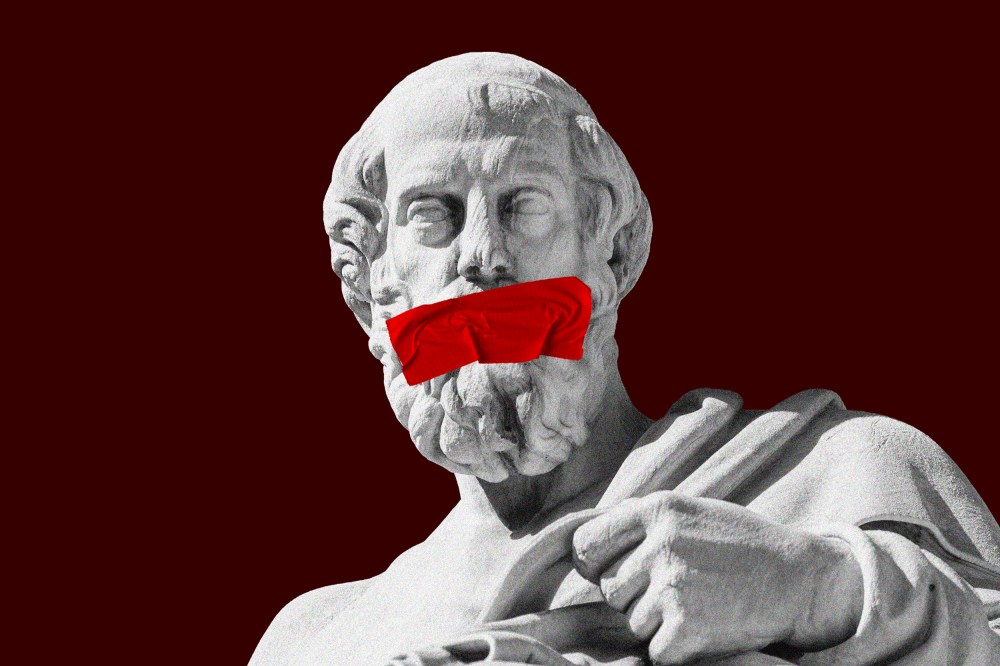

I have been to Athens many times, and on every visit I make a point of stopping by the site of Plato’s Academy, the world’s first university, founded around 387 BCE. Whereas other schools at the time primarily trained students in rhetoric and the art of winning debates, Plato explicitly urged his students to seek the truth — even when it was uncomfortable or controversial. It is precisely this attitude toward teaching and research that has made American universities the best in the world. We do not Make Universities Great Again by censoring the classics.

We do not Make Universities Great Again by censoring the classics.

The ban on teaching Plato’s “Symposium” at Texas A&M is, in a sense, understandable. If one accepts the university rule, adopted in November, that bans the teaching of “race and gender ideology,” Plato joins a long list of prominent thinkers whose ideas might be deemed corrupting to youth and therefore subject to censorship.

In the “Symposium,” Plato describes homosexuality as fully natural and suggests that there are more than two genders: “you should learn the nature of humanity … in times past our nature was not the same as it is now, but otherwise. For in the first place there were three kinds of human being and not two as nowadays, male and female. No, there was also a third kind, a combination of both genders.”

Upon being notified that part of my course curriculum for “Contemporary Moral Issues” was not compliant with university policy, I was, in one respect, pleasantly surprised that high-level administrators at Texas A&M know their Plato so well. But it was still a shock that they were unwilling to let this pass.

Plato explicitly urged his students to seek the truth — even when it was uncomfortable or controversial.

I was offered the option to remove the noncompliant passages from my course syllabus or be reassigned, to teach a different philosophy class. I informed administrators that I would replace the offending modules with lectures on free speech and academic freedom.

For the record, Plato can hardly be accused of being a left-wing extremist. He explicitly rejects democracy in favor of enlightened philosopher-kings. He is the go-to philosopher for authoritarian leaders seeking to limit free speech, academic freedom and much else we have taken for granted for generations. So, isn’t he exactly the kind of philosopher I should ask my students to read if my aim were to please the conservative leaders responsible for the new censorship policy?

To be clear, I am not a left-wing extremist; I am firmly middle of the road. I know I am not alone at my institution. A former student recently sent the following message to the university provost and president, cc’ing me, which I quote with permission:

“I benefited from being challenged by professors at Texas A&M during my undergrad studies. I chose A&M because it was a safe, ideologically conservative campus. And yet, as someone who went to Christian school K–12, my professors and my classmates challenged me to rethink some things, to evaluate for myself what I believed. It was a good exercise, and I came out a better person because of it. I came out a stronger Christian.”