On Tuesday, Vice President JD Vance spoke at an event in Pennsylvania focused on affordability. In keeping with the administration’s approach to the subject, it was a bit scattershot, presenting to the audience bold claims of how effective President Donald Trump’s policies have been, but also blaming prices and other bad news on former President Joe Biden.

The timing was also tricky. A few hours before Vance stepped onto the podium, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that unemployment hit a four-year high in November. Trump recently claimed that his handling of the economy deserved an “A-plus-plus-plus-plus-plus,” as though he was the daydreaming kid in “A Christmas Story.” In Pennsylvania, Vance agreed with that assessment. But the new jobs data suggests that his real grade might at best instead land somewhere in the Cs — like the daydreaming kid in “A Christmas Story.”

Vance was asked about the weak employment data at the Pennsylvania event, including a drop of 100,000 in October. The vice president had an explanation ready to go.

“When you talk about 100,000 jobs, you’re talking about government sector jobs,” Vance said. “That is, in a lot of ways, the entire story of what we’re trying to do under President Trump’s leadership. We want to fire bureaucrats and hire these great Americans out here.”

Vance’s point about the source of the 100,000-job drop is generally correct. In both October and November, much of the decline in employment was driven by employees of the federal government, in part thanks to the extended government shutdown that affected both months.

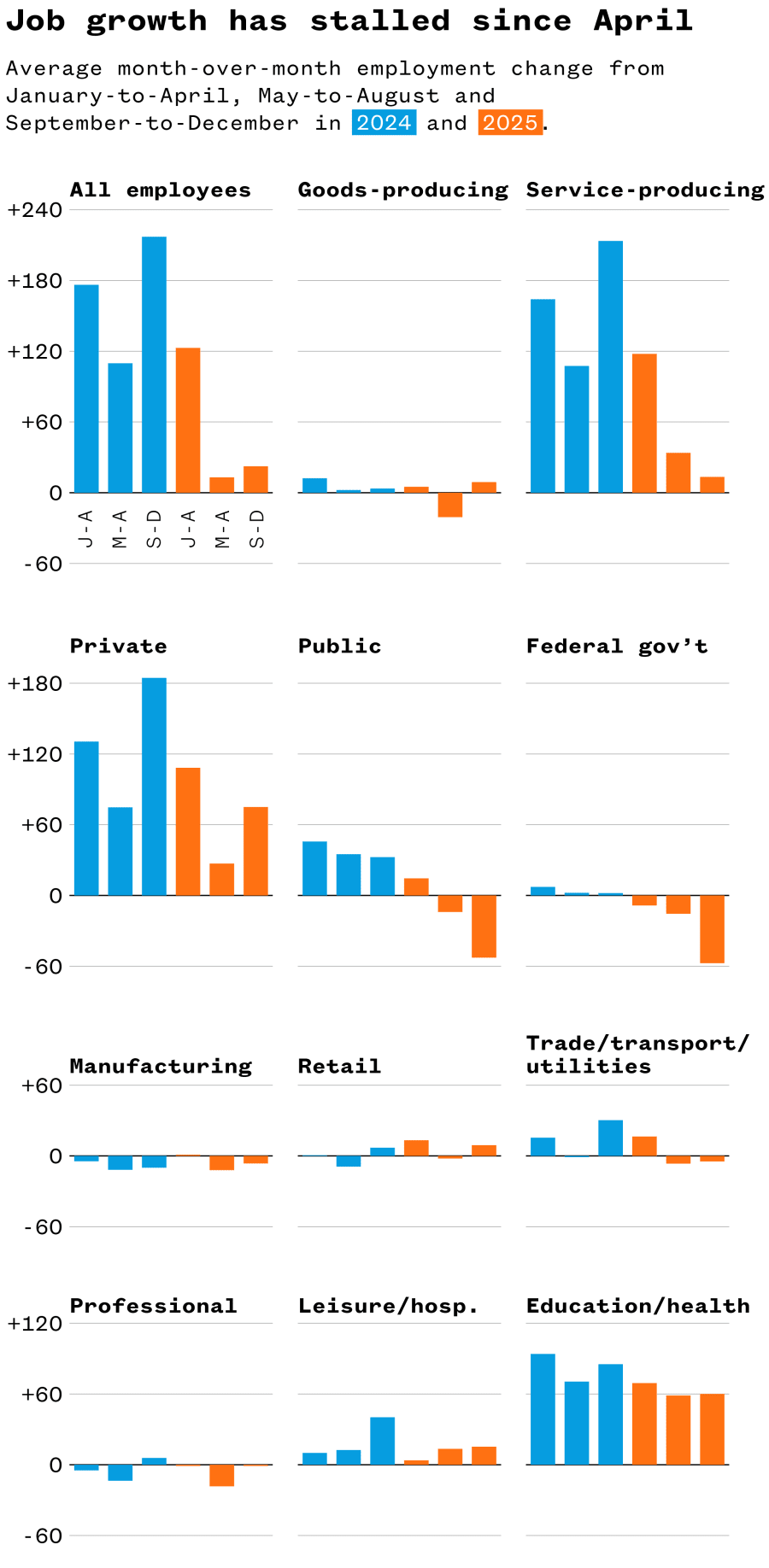

But the shifts in employment seen even before the shutdown were sluggish by the standard of recent employment reports. This suggests that the drop in government employment has only partially been offset by private-sector gains.

Since January, the number of people working in the U.S. has increased. That’s entirely because of private-sector job growth. But this is not a function of the manufacturing renaissance Trump promised. Instead, it’s centrally because of an increase in the service sector, specifically education and health care. Ninety-two of every 100 jobs added since January have been in the education and health care sector.

Growth in other sectors has been more modest or has fallen since Trump took office. (Jobs numbers reflect employment at the beginning of each month, which is why job losses from the shutdown continued into November and why comparisons with January are useful to see shifts since Trump took office.)

If we consider changes in employment in relative rather than absolute terms (that is, as a percentage shift instead of a raw total), you can see these patterns: stagnant public sector employment — even before the shutdown — and decreases in manufacturing and professional employment. You can also see that the decline in federal employment was well underway before the shutdown.

It’s also worth noting the callousness of the distinction that Vance draws between government and non-government jobs.