President Donald Trump continued his like-loathe relationship with The New York Times recently, sitting down for a two-hour interview and tour of the newly bedazzled White House. At one point, the newspaper’s David Sanger asked Trump if he thought the Civil Rights Movement had ultimately worked against white men. Trump said that it had.

“White people were very badly treated, where they did extremely well and they were not invited to go into a university or a college,” Trump said. “So I would say in that way, I think it was unfair in certain cases.” He later added that “it was a reverse discrimination.”

It is impossible to overstate how important this idea is to Donald Trump’s politics.

Trump did not inject this idea into Republican politics. If anything, he merely leveraged it.

It’s buried in his long-standing slogan, “Make America great again.” America was once great, but what changed? Well, one thing that changed is America got more diverse and welcomed immigrants from around the world, a change that corresponded with the massive baby boom generation (of which Trump is one of the earliest members) getting older.

But Trump did not inject this idea into Republican politics. If anything, he merely leveraged it.

Consider the tea party, the right-wing movement that emerged nearly two decades ago in the wake of the global recession and, more specifically, the election of Barack Obama as president. The movement was ostensibly predicated on frustration with being taxed (hence: tea party), but was rooted more firmly in cultural complaints.

In their 2011 book, “The Tea Party and the Remaking of Republican Conservatism,” political scientists Theda Skocpol and Vanessa Williamson explained what they’d learned from conducting hundreds of interviews with tea party activists.

“In Tea Party eyes, undeserving people are not simply defined by a tenuous attachment to the labor market or receipt of unearned government handouts. For Tea Partiers, deservingness is a cultural category, closely tied to certain racially and ethnically tinged assumptions about American society in the early twenty-first century,” they wrote. “Tea Party resistance to giving more to categories of people deemed undeserving is more than just an argument about taxes and spending. It is a heartfelt cry about where they fear ‘their country’ may be headed.”

It wasn’t really about the taxes. It was that their taxes were going to people who didn’t deserve it. Big corporations? Sure, sometimes. But also minorities and non-natives.

“Compared to other Americans, including other conservatives,” Skocpol and Williamson wrote, “Tea Party participants more readily subscribe to harsh generalizations about immigrants and blacks.”

Trump was heavily invested in tea party politics. His ultimately abandoned bid for the Republican presidential nomination in 2012 included frequent appeals to tea party supporters, leveraging the fringe-right rhetoric that many of them had embraced. That he gained notoriety primarily for dishonestly questioning Obama’s birthplace is very much to the point. Again, though, this was heavily because Trump mirrored this racial insecurity more than that he initiated it.

A plurality of Republicans to this day believe that the differences are rooted in Black peoples’ lack of will power.

Four years later, he actually ran for president. By the time he made his campaign announcement, in June 2015, the landscape on issues of race and immigration had shifted dramatically. The Obama administration, for example, had scrambled to deal with an influx of children arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border in 2014, an issue that right-wing media seized upon to elevate immigration as a political issue. That same year also brought the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, a conversation about race and policing that both raised the salience of race and sharply polarized views of how non-white people are treated in the U.S.

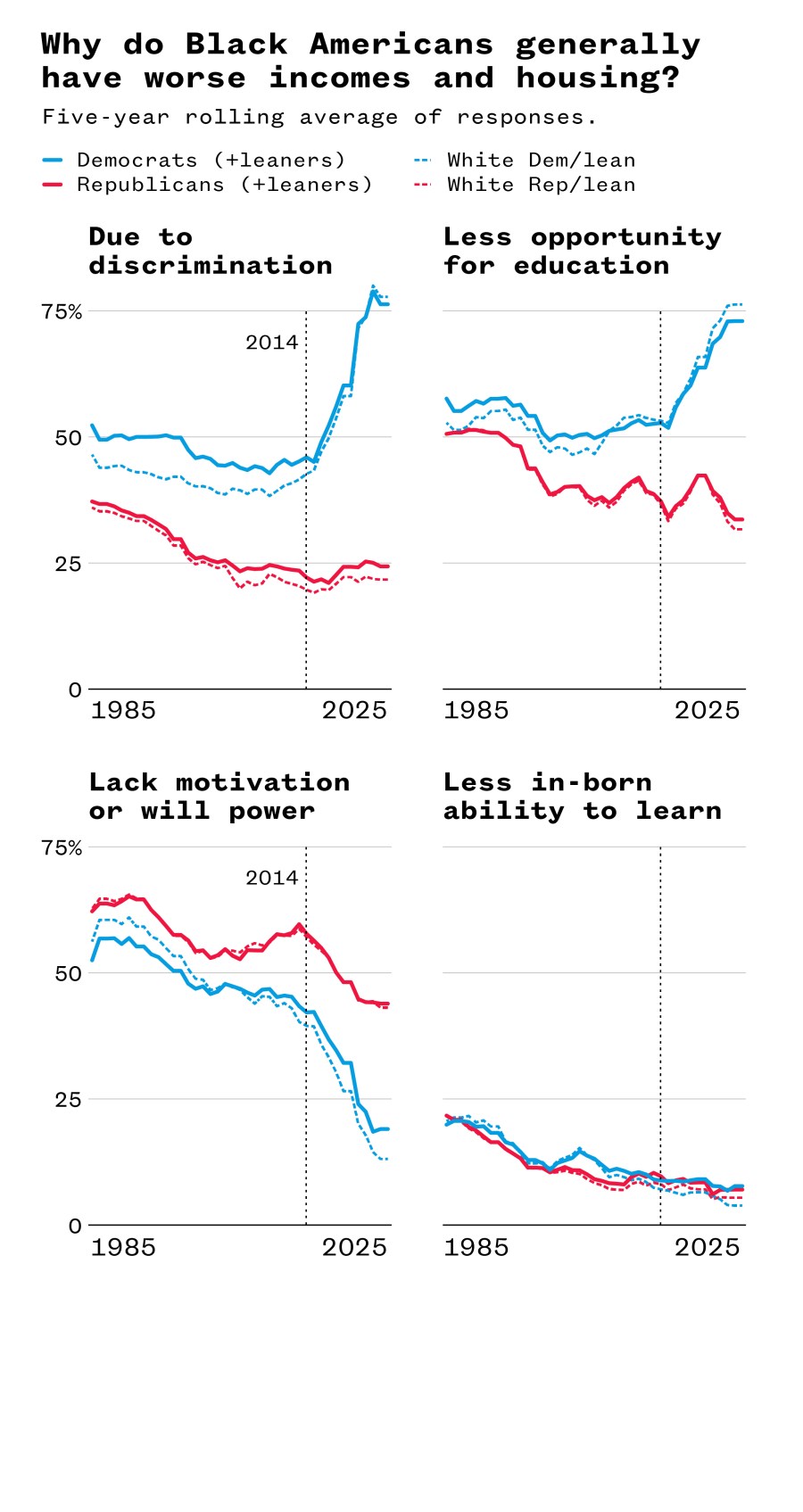

The General Social Survey, a biennial national poll, has been asking Americans since the 1970s why Black Americans generally have lower incomes and worse housing than white Americans. It used to be the case that Americans were most likely to attribute this difference to a lack of motivation or willpower. After Black Lives Matter, however, that shifted, with a surging percentage of Americans attributing the difference to discrimination.

That change, though, was centered among Democrats. Among Republicans, BLM drove no significant new consideration of discrimination as a root cause. Instead, a plurality of Republicans to this day believe that the differences are rooted in Black peoples’ lack of willpower.

When Trump announced his 2016 candidacy, he focused his remarks on immigration, on the idea that foreign countries were sending criminals into the U.S. At first, Republican officials explicitly rejected Trump’s rhetoric, presumably assuming that his candidacy stood no chance. In a little more than a month, with enormous attention paid to his comments on immigration, he was the front-runner.

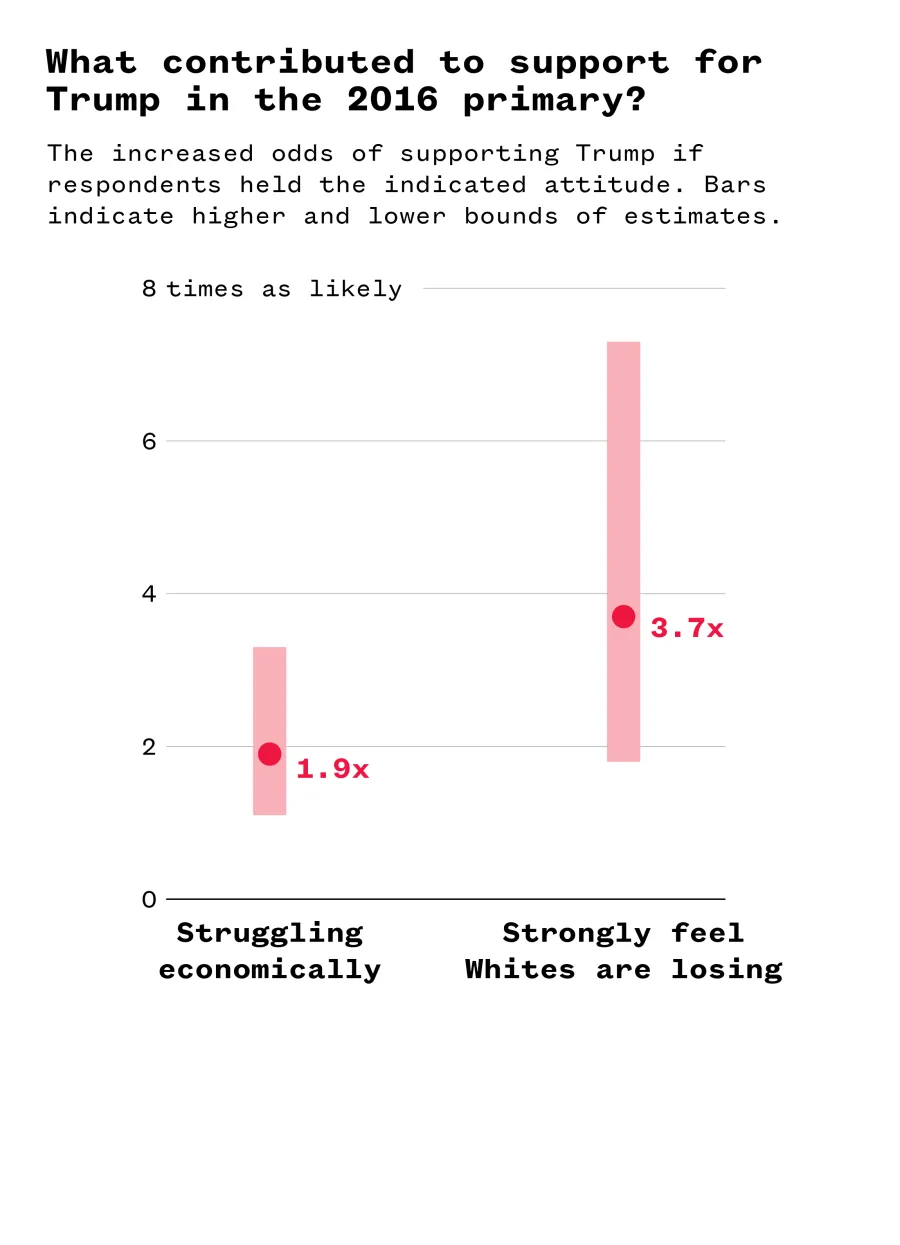

Racial insecurity was an important part of that success. In March 2016, The Washington Post and ABC News conducted a poll measuring support for different Republican candidates. The outlets discovered that economic insecurity was a significant driver of support for Trump over other candidates, with those who said they were struggling being about twice as likely to back Trump’s candidacy.

But a stronger motivator for Trump support was a sense that white people are “losing” in modern society. Those who held that position were nearly four times as likely to back Trump.

It’s probably not necessary to articulate the ways in which Trump’s 2016 candidacy and first term in office served as a response to that sentiment. There have been numerous analyses of how racial animus motivated Trump as president; no such analysis is required to understand how hostility to immigrants manifested.