U.S. AND ISRAEL STRIKE IRAN

BREAKING

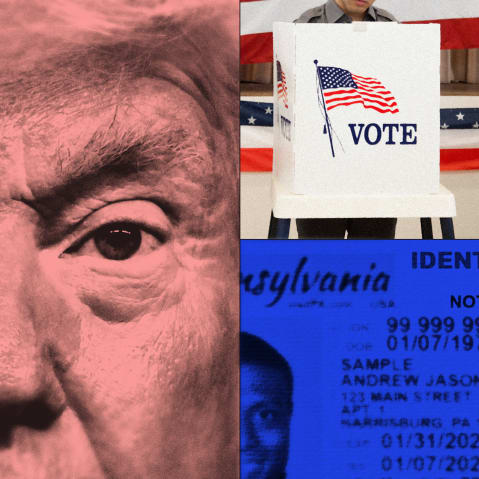

U.S. launches ‘major combat operations’ in Iran, Trump says

Erum Salam & David Rohde

Trump acknowledged that “Operation Epic Fury,” the U.S.-Israel military offensive in Iran, could lead to American casualties, but said the mission was necessary to protect America and its allies in the future.

MS NOW OPINION

Understand Today’s News

The very real consequences of RFK Jr. and Kid Rock’s online fitness stunt

Natalia Mehlman Petrzela

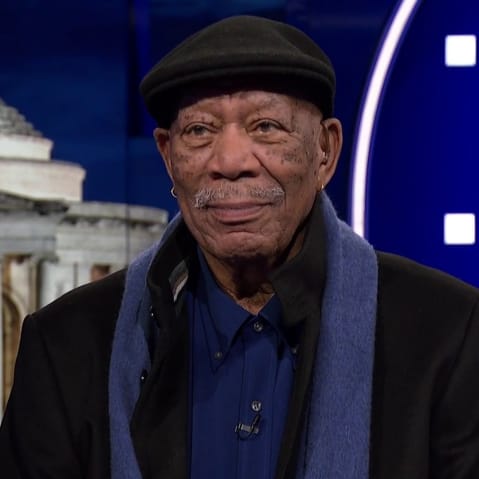

Jesse Jackson was an unapologetically Black American hero

Charles F. Coleman Jr.

Like this content? Follow our rundown delivered daily right to your inbox

Shows

Know Your Value

Latest from MS NOW

Morning Joe