Black River, Jamaica, was the first spot on the island to be electrified, back in 1893. After Hurricane Melissa tore through this week, much of the island is in the dark, and according to Prime Minister Andrew Holness, Black River has been “totally destroyed.”

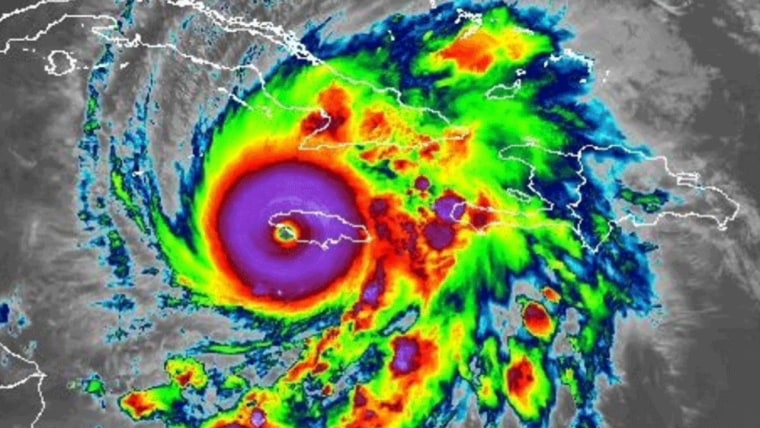

Jamaica felt the full wrath of Melissa, a storm that needed only 24 hours to intensify from a tropical storm to a Category 4 behemoth. By the time it made landfall only 10 or 12 miles from Black River in New Hope, it had grown even stronger: Category 5, 185 mph winds — or maybe even stronger — and a slow, meandering pace that let it lash its targets with that wind and rain for too long.

This has become a grim hallmark of a warming world.

This has become a grim hallmark of a warming world. Rapid intensification of hurricanes relies on conditions that in decades past were much more rare than they are today. A 2023 study found that the average maximum rate of intensification was almost 30% higher from 2001 to 2020 than it was between 1971 and 1990; the number of storms that leap from Category 1 to Category 3 or higher within 36 hours has “more than doubled” in that modern era compared to in the past. Since that study came out, we have witnessed, among other examples, Hurricane Milton’s wind speed jump 95 mph in a day.

The main culprit is heat. Abnormally warm waters — both at the surface and down below — helped Melissa gain strength, even as it took a leisurely path that in a normal world would likely lead its power to wane. That warmth is being added, year by year, via the greenhouse gases the world continues to emit. Saying so has become cliche at this point, but once again, it’s necessary to point out that the countries barely responsible for the emission of greenhouse gases are bearing the brunt of the consequences.

In 2023, excluding land-use changes, Jamaica emitted less than eight million tons of carbon dioxide. The U.S. emitted that much every 14 hours or so. In China, that number would be less than six hours. In a single year, the U.S. emits 10 times as much carbon dioxide as Jamaica has emitted ever, in total. And Haiti, where at least 23 people have died from Melissa’s impacts, emits half the carbon dioxide Jamaica does.

The other anomaly facing Jamaica and the rest of the region isn’t climatological, but governmental. The Trump administration has made some promising noises this week about providing aid as the damage becomes more clear, but it is doing so after nine months of attempts to kneecap a wide swath of government function and while, notably, the federal government remains shut down. Already, the difference in response to disasters rich countries’ emissions have helped fuel is plain: Only a year ago, the United States Agency for International Development, or USAID, sent staff and supplies to the Caribbean before Hurricane Beryl arrived on its tear through the region, along with coordinating the response once it had passed. This time, USAID is … gone.

While the relatively poor nations of the Caribbean will face down perpetually microwaved waters and the storms they produce from here on out, the U.S. itself is, of course, not immune from hurricanes. Though much of the related devastation the country has faced in recent years was due to the storms’ water rather than wind — recovery is still ongoing a year after Helene, for example — no place in the country would be safe from, essentially, an EF4 tornado blown out to hurricane size.

Only a small handful of hurricanes have made landfall in this country as a Category 5 storm. Only one, the 1935 Labor Day Hurricane, had wind speeds to match Melissa’s ferocity, and though it killed more than 400 people in the Florida Keys and elsewhere, it occurred far too long ago to offer much in the way of lessons. Hurricane Andrew, however, perhaps does offer a glimpse into what almost seems like an inevitable future.

No place in the country would be safe from, essentially, an EF4 tornado blown out to hurricane size.

That 1992 storm, which devastated the Miami area after making landfall with 165 mph winds — still 20 mph weaker than the punch Melissa packed — destroyed tens of thousands of structures and damaged many more, for a total cost of roughly $26.5 billion (upward of $60 billion in today’s dollars). In its wake, Florida revamped its building codes, and as a result, most new construction is significantly stronger than it used to be — of course, not all construction is new construction, there are a lot more coastal structures than there used to be and whatever enormous waves get kicked up will be starting from a higher point due to sea levels rising.

A 2017 analysis by insurance giant Swiss Re found that if Andrew returned in its exact same form, it would cause upward of $100 billion in damage; if it veered 20 miles north and actually struck downtown Miami, that number would rise to nearly $300 billion. (That’s $130 billion and $400 billion today.) And of course, not every state has Florida’s building codes.

“No matter how much you prepare for a Category 5 hurricane, it’s horrendous to experience,” said Lixion Avila, a retired NOAA hurricane specialist who was on staff at the National Hurricane Center during Andrew’s rampage, on the storm’s 30th anniversary. As Black River and the rest of Jamaica, Haiti, Cuba and more start to dig out and rebuild, the sentiment rings grotesquely true. And in a warmer, warming world, more and more people — in the Caribbean as well as in the U.S. — are likely to join a grim, catastrophic club.