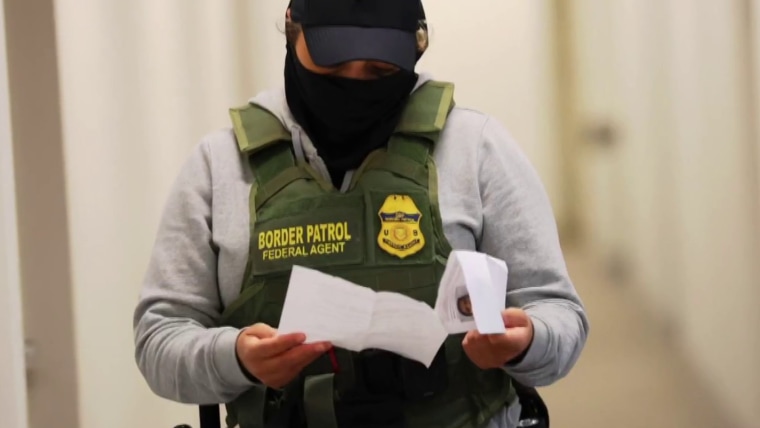

One of the signature provisions of the giant spending bill that congressional Republicans passed back in July was an astounding increase in the budget for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE. The bill allocated $170 billion over four years to the Department of Homeland Security, with $30 billion earmarked for ICE, making it arguably the most well-funded of all the federal law enforcement agencies. The surge in funding was intended in no small part to help ICE hire 10,000 more enforcement officers by the end of 2025, which if achieved would more than double their numbers, from roughly 6,000 to about 16,000.

But just because an agency wants to increase staffing, that doesn’t mean it will be able to do so easily, and I predicted back in July that ICE would likely struggle to meet this goal.

While the low quality of ICE recruits is making it harder for them to hit their target, it also means the ones they do hire are likely to be less qualified, and thus more likely to do even more harm when deployed.

This was due, in part, to past difficulties. A similar effort to expand ICE staffing during President Donald Trump’s first term fell short, and a recruitment drive for the Customs and Border Protection Agency, or CBP, resulted in serious concerns about sharp declines in officer quality and trustworthiness. Both processes also had striking failure rates, with one internal report suggesting that ICE would need more than 500,000 applicants to achieve a net increase of 10,000 (and CBP would need to interview 750,000 to add 5,000).

Moreover, the current surge in ICE hiring comes at a time when local police forces — many of which pay better, have better working conditions (such as staying close to home) and broader social support and respect — struggle, along with almost all other government agencies, to fill open positions.

On paper, ICE seems to be well on its way to hitting its goal. A September press release said ICE had received more than 150,000 applications over an unspecified period, from which it had made 18,000 tentative offers — nearly double its target. But it is increasingly clear that the press release painted an unduly rosy picture, and that in practice, ICE is struggling to meet its goal, especially with only three months left to meet its (self-imposed) deadline.

To start, it looks like those 150,000 applications are close to only 50,000 actual people, since a person applying for multiple jobs apparently counts as multiple applications (even though they can only fill one of them). If the success rate from Trump’s first term still holds (and things may actually be worse than before!), that would translate into roughly 1,000 successful hires, just 10% of the goal.

And ICE’s own actions make it clear all is not well. In August, ICE chose to eliminate its age requirements, which used to require applicants to be at least 21 years old and no older than 37 to 40, depending on the job. Now ICE is open to deploying 18-year-olds.

DHS made 59-year-old actor Dean Cain — best known for his role in the mid-1990s TV show “Lois and Clark: The Adventures of Superman” — an honorary ICE officer. When asked for clarification on what responsibilities Cain’s honorary role entails, DHS didn’t respond, but assistant homeland security secretary Tricia McLaughlin said in an email that “ICE waived age limits for new applicants” and “Superman is encouraging Americans to become real-life superheroes by answering their country’s call” to join ICE “to help protect our communities to arrest the worst of the worst.”

ICE is also spending millions of dollars on an aggressive television ad campaign targeting current local and county police officers, encouraging them to leave their current jobs to sign on with ICE — a move that is angering many of those departments, with whom ICE often needs to cooperate. It’s also worth noting that while several police departments have refused to comment on the ads, those that have commented said they don’t believe they’ve lost any officers because of the advertising, with at least one pointing out that even with all the incentives ICE is offering, the local department still pays better.

ICE is also spending millions of dollars on an aggressive television ad campaign targeting current local and county police officers.

Moreover, it’s become clear that many of the recruits ICE is getting are not up to the task. One investigation by The Atlantic reported that one-third of the recruits at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center, or FLETC, have failed a relatively modest physical test (15 push-ups, 32 sit-ups and 1.5 miles in 14 minutes). A report by NBC News stated that about half have failed an open-book and open-notes test on immigration and constitutional law.

Now, to be clear, applicants with prior law enforcement experience are not required to attend the FLETC program, and ICE claims it expects as many as 85% of new recruits to have that background, so the failure rate reflects (perhaps) a small, self-selected part of the applicant pool. But that 85% number from ICE was aspirational. They said they expect that figure, not that they have achieved it, and so far, police departments are not reporting significant attrition to ICE.

And if the 85% are made up largely of candidates who have previously quit or retired from the police, they are likely to be older and less in shape. Amid the HR chaos of trying to process so many applications, some actually qualified candidates who appear qualified claimed they’ve heard nothing from the agency about their candidacies.

Compounding all of this is the fact that the goal is a net increase of 10,000 officers, and there are already growing reports of stress and burnout among ICE officers. And no wonder, they’re often finding themselves deployed in cities that aggressively protest against them, and assigned to tasks — such as arresting day laborers outside of Home Depot — that pale in comparison to the overwrought rhetoric of saving the U.S. from murderers and terrorists.

It also surely doesn’t help to work for an agency that is one of the few with a net negative favorability ranking, second only to the IRS as the least-liked government agency. While there has been no significant level of quitting yet, combine the burnout with the ongoing shutdown — which may make potential recruits wary, especially those already with stable police jobs — and it seems likely that in the near future, some chunk of any new recruitment class will just be used to replace the officers who retire or quit, straining the recruitment goals all the more.

None of this is to downplay the very real harm that ICE is doing. And while the low quality of ICE recruits is making it harder for them to hit their target, it also means that the ones they do hire are likely to be less qualified, and thus more likely to do even more harm when deployed. But it is clear that Trump and his immigration consigliere, deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller, hope to build up ICE as a way to strike out at Democratic cities, and the ongoing struggles to hire more people suggest that goal may prove elusive.