GUATEMALA CITY, Guatemala — On June 29, the summer heat in Los Angeles, California, was beginning to rise.

Seventeen-year-old Nory Sontay Ramos and her mother, Estela Ramos Baten, slipped into jeans and T-shirts and headed to a relative’s home for a Sunday family gathering.

Inside the kitchen, Nory’s uncle chopped tomatoes and cilantro, squeezed limes and prepared ceviche using a recipe from their native Guatemala. As they ate, the family laughed and shared plans for the week ahead and the rest of the summer. Nory, an honor student and athlete, was excited about her cross country practice the next day. Making this meal, around the corner of their own home, was a family ritual, one mother and daughter had enjoyed since migrating to Los Angeles in 2016.

In another room, Nory and her cousin Yuri Ramos swapped stories about school and their plans for senior year at Miguel Contreras Learning Center in the Westlake District. They chatted about which classes to take, what clubs and sports to join, and, most importantly, what dresses they might wear to prom. They also mapped out Nory’s upcoming 18th birthday celebration — friends, laughter and In-N-Out burgers.

We went to a little room, and they told us to sit down. They closed the door and said, ‘I’m sorry to say this, but your case is over. We will take you guys with us.'"

Nory Sontay Ramos

But back in the kitchen, the mood was getting heavier. Estela shared that during a recent routine immigration check-in — one of many in her yearslong attempt to adjust her immigration status in the U.S. — officials told her something new: They wanted to see Nory, too. A fresh appointment was arranged for the following day, Monday, June 30.

With immigration raids sweeping Los Angeles neighborhoods and President Donald Trump making mass deportations of noncriminal immigrants a cornerstone of his administration, the family feared the worst. “I had a bad feeling,” Nory told MSNBC. But her mother insisted they had to attend, saying they needed to “do things the right way.”

The next morning, Estela woke Nory up. They ate a quick breakfast and set out. The appointment was scheduled for 10 a.m., but Estela wanted to arrive an hour early.

From the start, Nory sensed something was wrong. “We were there waiting for hours, with no information. Our appointment time passed, and we were still sitting there. Every time we asked questions, they said they had a lot of paperwork to review.” Their lawyer, Nory added, didn’t make things better. “She was antsy. She kept saying she had more work waiting at her office, but my mom begged her to please stay longer. Hours later, an officer finally called our names.”

They were taken into a room filled with people who, Nory said, “looked worried.” After another stretch of waiting, officials finally called them in — and everything changed in an instant. “We went to a little room, and they told us to sit down. They closed the door and said, ‘I’m sorry to say this, but your case is over. We will take you guys with us.’”

They were being deported.

Estela, who does not speak English, asked Nory in their native K’iche’ Mayan dialect to translate. When Nory repeated the words, Estela said it felt as if her world had just collapsed. Their attorney tried to intervene, insisting they would fight the decision, but the officials were unmoved. “Get ready, you are coming with us,” they were told. By then, it was nearly 11 p.m.

That night, Nory and her mother were taken straight to the airport, flown to Houston, Texas, and then transferred to the Dilley Immigration Processing Center, about an hour south of San Antonio, where they stayed for two days. “They treated us good, but it was really tough,” Nory remembers. “They gave us beds, and they were like, you guys can exercise and there’s food.” But whenever they asked questions, they were ignored. They were only told by staff at the processing center that an ICE officer might contact them about their case, a small glimmer of hope that they might still remain in the U.S.

That’s not what happened.

“On Thursday night, my mom and I were about to go to take a shower, and two agents came in and called us. They said ‘Pack your things. You guys are leaving.’ We asked where we were going and they said, ‘Oh, we cannot tell you. We don’t know anything. We just follow the rules.’” Nory and her mom were then driven to “a small place” where migrants in handcuffs were coming off a bus. Nory said she was shocked to see them like that, so before getting out of the car, she decided to speak up. “I asked him, ‘Where are we going? Can we make a phone call? Because we want our family to know you guys are just taking us.’ And they were like, ‘No, your family already knows where you guys are going,’ and he just slammed the door of the car.”

The next day, as fireworks lit up the sky on July Fourth, they were loaded onto a deportation flight.

Nory and Estela were not allowed to return home to pack a bag, say goodbye, or even make a phone call. “I was just looking at my mom, crying,” Nory said. “I was just sad, I was lost. I didn’t know what I was going to do. My mom held my hand and said, ‘Don’t worry, Nory. Everything will be OK.’”

There have been over 5,000 arrests in Los Angeles since the Trump administration ramped up immigration enforcement in early June, according to Homeland Secretary Kristi Noem. Just like with Nory and Estela, in June and July, nearly 60% of migrants arrested in Los Angeles had no criminal conviction nor pending criminal charges, according to data provided to MSNBC by Dr. Austin Kocher of Syracuse University, a political and legal geographer focusing on the politics and policies of the U.S. immigration and refugee system. That percentage of noncriminal arrests in Los Angeles is more than double the average over the previous 16 months.

The mother and daughter’s apprehension inside immigration court is part of a nationwide trend. In a shift from precedent, the Trump administration has targeted immigration courthouses across the country as enforcement zones. The practice has happened largely out of the view of the public, save most notably at immigration court in lower Manhattan where MSNBC has observed the systematic arrests of migrants appearing for routine hearings. The surprise courthouse detentions have spurred several federal lawsuits against the practice, alleging it violates migrants’ rights to due process. In a statement, Tricia McLaughlin, a spokeswoman for the Department of Homeland Security said the courthouse arrests were “a common sense” approach that saves time because Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers “already know where a target will be.”

Hours later, they landed in Guatemala, a country Nory had left as a small child and barely recognized. They arrived wearing the same clothes they had put on for their immigration appointment. From that moment forward, those were the only belongings they had.

With no money and no working phones, they begged Guatemalan officials for one call. When Estela finally reached her eldest daughter in Los Angeles, panic set in. She hadn’t heard from her mother and sister in four days and had no idea they had been deported. The daughter — whom MSNBC is not naming for security reasons — then alerted relatives in Guatemala, asking them to pick up Estela and Nory at a bus station after officials put them on a bus bound for Quetzaltenango, four hours west of Guatemala City.

Back in Los Angeles, Nory’s cousin Yuri could hardly believe what she was hearing.

Through tears, she recalled that the night before the appointment, while sharing ceviche with Nory and her aunt Estela, they had trusted the lawyer’s reassurance that everything would be fine. “The lawyer said that it was going to be OK to come in, to bring Nory to the appointment.” She paused, struggling to breathe through her sobs, before adding: “They are targeting us. We are just people trying to make a living here like everyone else.” We reached out to Nory and Estela’s lawyer for comment but are yet to hear back.

The family had to push through the pain to focus on the bigger issue at hand. They had to find a safe place for Nory and Estela to stay, far from the dangerous people and threats they say had driven them out of Guatemala in the first place.

A childhood in fear

Nory was 8 years old when she first entered the United States.

At the time, she spoke only K’iche’, the language of her Indigenous Mayan community. Spanish — Guatemala’s national language — was unfamiliar, and her mother feared sending her to school to learn it because of threats from local gangs.

According to their sworn asylum declaration, obtained exclusively by MSNBC, members of Calle 18 — also known as the 18th Street Gang, one of the largest youth gangs in the Western Hemisphere — had been targeting Estela and her children since 2014. That year, Estela separated from her husband and moved back into her parents’ home in the remote village of Pitzal, in Momostenango, about an hour north of Quetzaltenango. Without a husband, Estela explained, she was seen as vulnerable, an easy target for gang recruitment.

In her declaration to U.S. immigration officials, Estela wrote that the gang members “robbed and killed people” and that she refused to join them or allow them near her children. She feared that if she stayed in Guatemala, she could be killed “leaving my children without a mother.”

The declaration includes the names of the gang members allegedly pressuring her, though Estela asked MSNBC not to publish them, terrified of retaliation. She described how one gang leader once gave her a stark ultimatum: “Join the gang or he would pull out his gun and shoot me.”

For Nory, then a child, the threats were constant. Most days she was kept indoors, not allowed to attend school or play outside, as her mother feared she could be kidnapped or attacked if she ventured out. That fear defined their lives until one afternoon in late 2015, when it escalated to violence.

“We heard someone banging on the door,” Estela told immigration officials. “When I opened it, eight people entered the house. … Suddenly [one of the gang members] began hitting me in the face, dragging me by the hair across the floor, and shouting: ‘This is my final warning. If you don’t change your mind, the next time I see you on the street, I’ll kill you.’”

Nory, watching, fainted from the shock. She was 8 at the time. “When everything happened — everything they did to my mom — I passed out,” she recalled. “All I remember was just being scared.”

Estela, badly injured, says she ended up in the hospital. She filed a police report, but that only seemed to anger the gang further. That night, after seeing her daughter faint and her own face bloodied, Estela decided there was no future for them in Guatemala.

The journey north

In late April 2016, Estela’s father helped her and Nory flee the country.

They boarded a bus to Huehuetenango in the dead of night and continued on to La Mesilla, the border crossing between Guatemala and the Mexican state of Chiapas. They carried only what Estela’s father could scrape together — about 200 quetzales, the equivalent of $26 at the time.

To stretch their money, they bought candy along the way and sold it to cover food and shelter. They traveled for nearly 12 days, inching their way across Mexico until they reached San Luis Río Colorado, just across the border from San Luis, Arizona.

There, U.S. Border Patrol agents quickly intercepted them. Estela, with her limited Spanish and no English, tried to explain her case as best she could. She was eventually placed into removal proceedings but allowed to present her case to an immigration judge.

Officials contacted a relative in California to sponsor them while their case was reviewed. On May 5, 2016, Estela and Nory were released from custody and moved to Los Angeles, the city they came to call home.

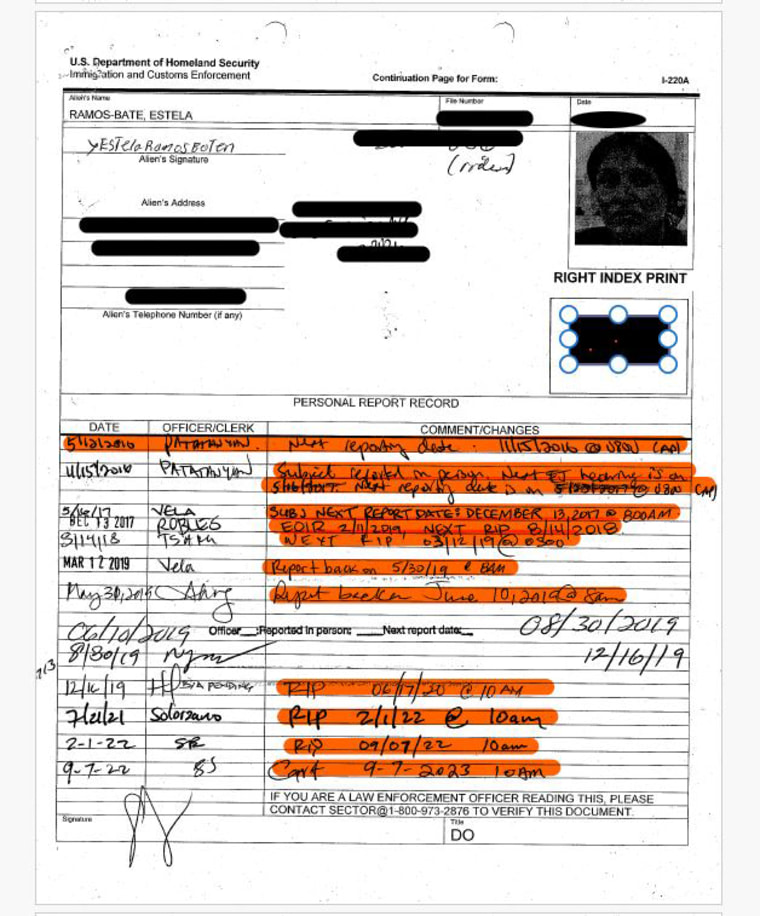

Their asylum case was ultimately denied, and the immigration court said that they “failed to demonstrate… or establish eligibility for asylum” in part because the evidence they submitted included “a photo [of one of the gang members threatening them] being arrested.” That person, Estela declared on immigration documents, was later released on bail and continued threatening her and her family. Notwithstanding, the judge denied the claim and granted Voluntary Departure in 2019. According to documents reviewed by MSNBC, the decision was appealed. As of March of this year, they had no warrants.

MSNBC reached out to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement for more information about this case, but they didn’t respond to requests for comment.

A new beginning

For Nory, Los Angeles was both challenging and transformative.

She enrolled in a neighborhood elementary school, and within months, she was speaking English fluently. The trauma she carried from Guatemala lingered, but with therapy, and with the support of friends and family, she said she slowly began to heal. Teachers noticed her work ethic, her determination and her optimism.

She began to see herself as, in her own words, “an L.A. girl.” She loved going to Sephora with friends, eating Chick-fil-A sandwiches, and practicing tae kwon do. She dreamed of attending Santa Monica College to study fashion design. A year and a half ago, she adopted a black cat and named him Max.

In the weeks before her deportation, Nory was preparing for her senior year at Miguel Contreras Learning Center, where she excelled both in class and on the track. She competed with the school’s cross-country and track team, the Cobras, and earned several awards this year — including one for her “significant growth across the 2025 season for the Contreras Track and Field Team.” Her classmates and teachers described her as a source of joy and encouragement.

“She’s just sweet. She embodies joy and love. We wish we could clone students like her,” said one of her teachers, Darcy White. When White learned that Nory and her mother had been deported, she said she felt devastated. “When I found out she was back in Guatemala on the Fourth of July, I posted just how not proud of this country I was. I told all my friends across the country — because I know teachers everywhere — ‘This is real. This happened to my student. And it’s not right.’”

White, who teaches Government, Principles of Democracy, and Economics, said she believes due process failed them. “I think both her mom’s and her rights were violated. Because it is not a matter of being a citizen of the United States. People who live here are protected by the Constitution. People who visit here are protected by the Constitution. And I teach this every day.”

Despite the distance, White has stayed in close touch with Nory through WhatsApp. She worked with the Los Angeles Unified School District to find a way for her to finish her senior year remotely. Just last week, the district assigned Nory a laptop so she could re-enroll as a “temporarily relocated student” and join the district’s virtual academy. “She’ll be able to complete her senior year online,” White said. “I even picked up the computer for her today.”

During our interview, knowing we would travel to Guatemala the next day to meet Nory, White asked if we could bring the computer to her. We agreed. She also sent notebooks, pencils, pens and a pair of running shoes so Nory could keep running. “I was buying these shoes for her yesterday, and I told everyone I met, ‘These are for my student. She got deported. It can happen to anyone here.’”

But in the nearly two months since Nory and her mother had returned to Guatemala, they had barely stepped outside their door. Both remain afraid that members of the 18th Street Gang could find them.

From senior year to survival

Quetzaltenango, Guatemala’s second-largest city, is known for its colorful markets, colonial architecture and dramatic views of surrounding volcanoes. But since their deportation nearly two months ago, Nory and her mother have not been able to see or enjoy any of it. They are living in a small house hiding from the same gang that forced them to flee years ago.

“We’re not safe at all here,” said Nory. "There are people looking for my mom, and we’re just really scared about what might happen if we go out.” Her mother added she doesn’t even feel safe going to church.

When we arrived at Nory’s new home, we followed careful instructions to avoid drawing attention. Before opening the door, Nory and Estela peered through a tiny window, anxious. Only after a long pause did they let us in. Inside, Nory greeted us with a wide smile — her warmth belying the fear in the air. She wore the same black sweater and sneakers she had on the day of her deportation. Her pants, she explained, were a gift.

The house itself is cramped and crumbling. Paint peels from the walls, and the kitchen connects to a small bedroom Nory shares with her mother. There is little furniture, no television and no internet. Only a few light bulbs illuminate the space. A friend helped them find the house, but the owner has already voiced concerns about gang members discovering them.

To stay safe, they rarely step outside, relying on that same friend to buy groceries. For Nory, a runner who once trained on Los Angeles tracks, the green trails that wind through Quetzaltenango, with panoramic views of volcanoes brushing the clouds, might as well be a world away. “I don’t really go out,” she said. I’m just here at home. It’s been two months now.”

During our time in the house, we noticed that every sound outside made Estela jump. “I think they know where we are,” she whispered in broken Spanish. “My friend heard the gang leader is asking questions about me. Where is Estela?”

Despite the fear, Nory remains determined. She carefully unpacked the backpack filled with supplies and the laptop her teacher, Darcy White, sent. Her eyes lit up, a spark of happiness breaking through. But the joy quickly gave way to worry: There was no internet in the house, and leaving to find a connection seemed too dangerous.

Still, she promised she would not give up. “I’m really grateful for the opportunity they gave me to just study from here. I’m going to keep it up and not give up. … And if I make it back, I’m definitely going to go to college to make my mom proud and make myself proud as well. Make everyone proud.”

Borrowing one of our phones, Nory called Ms. White to thank her. Fighting back tears, she said, “I received the computer, and I received everything you sent me. I really appreciate it. Thank you so much.” On the other end of the line, White reassured her: “I’m going to try to find out what the internet provider is there, and we’ll work on getting that set up for you.”

Between smiles and tears, Nory promised: “I’ll do my best here, and I will make you proud.”

White didn’t hesitate: “I’m proud of you every day.”

A painful goodbye

After the call with her teacher, Nory wiped her eyes and stood up.

She pulled a note from her jeans pocket and handed it over. “Could you give this to Ms. White, please? I want to thank her for sending the computer.”

As we packed the note and our cameras, Nory seemed to know this was the end — the last bit of connection to the U.S., the only country she really knows.

“Thank you for coming all the way here,” she said quietly, her face a mix of sadness and fear.

As we pulled shut the heavy iron door guarding their house, we saw Nory holding onto her mother. Saying goodbye to us, a group of complete strangers, was the closest thing to closure she’s had since being deported.

Her story is one of thousands, yet deeply her own: a reminder of what is lost when a system meant to offer refuge instead sends children back into danger. But despite everything she’s going through — the threats, the fear, the academic setback and the crushing weight of reliving old trauma, what breaks her the most, she told us in tears, is leaving behind her cat, Max. “It really hurts me to think of him at home, alone. Maybe he thinks, like, I just abandoned him. I miss him.”

Through all the chaos, her heart is with him.