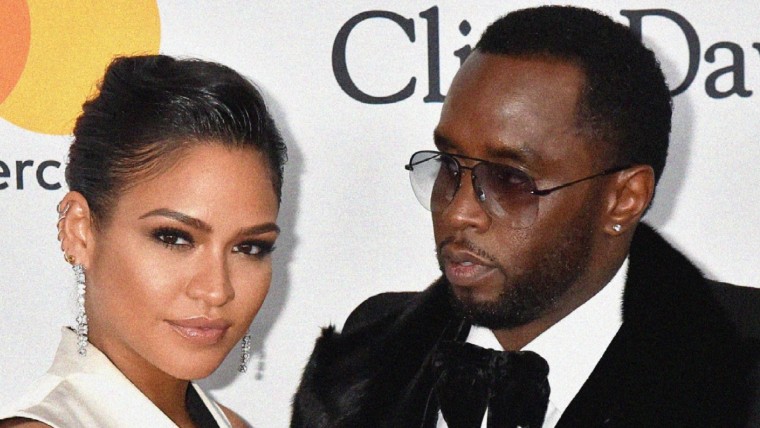

Ever since Sean “Diddy” Combs’ ex-girlfriend Cassie Ventura took the witness stand Tuesday at his sex trafficking trial in New York, her testimony has been riveting and terrifying.

For example, just before the trial broke for lunch Tuesday, Ventura explained how “freak offs” — or sexual encounters with a hired dancer or escort that Combs allegedly forced her to engage in and would watch, direct and film — almost became like a full-time job: “They ranged anywhere from 36, 48, to 72 hours. I feel like the longest one ever was four days, maybe even more, like, on and off with breaks. So it was a significant part of the week.” And that was before any of the necessary time to recover from, as she testified, “the drugs, dehydration, the just staying awake all that time.”

You might think that for a recovering litigator like me, that was the pivotal moment of Tuesday’s testimony. And you would be wrong.

Combs’ defense, after all, isn’t that the conduct never happened. There is simply too much evidence, much of it audiovisual, for them to deny the freak offs, the drug use and even Combs’ history of violence. Instead, they cast what happened to Ventura as a situation of her own making: a tumultuous relationship that involved drugs and third parties, but one that was always of mutual consent.

The prosecution, on the other hand, not only characterizes Combs as having engaged in a “persistent and pervasive pattern of abuse toward women and other individuals,” but also alleges that he led a criminal enterprise in which he used his various businesses and employees to carry out, facilitate and cover up his acts of violence, abuse and commercial sex, and conspired with members of the enterprise to commit crimes, including kidnapping, arson, and bribery to forced labor and sex trafficking. They’ve charged him with two counts of sex trafficking and two counts of transportation to engage in prostitution, but the most serious charge accuses him of participation in a racketeering conspiracy.

In order for the jurors to find Combs guilty of a racketeering conspiracy, they’ll have to find that there was an agreement between Combs and at least one other person to “conduct the affairs of a commercial enterprise” through a pattern of qualifying crimes. Put aside, for the moment, what does and does not count as a qualifying, or “predicate,” crime. At base, a racketeering conspiracy charge necessitates that the defendant has co-conspirators.

And that’s where Ventura’s first day of testimony was really instructive: as the groundwork for establishing the network of security guards, assistants and other business associates on whose help Combs allegedly relied.

She testified, for instance, that if she did not answer Combs’ calls, he would have his security or a trusted assistant keep calling until she answered and that he would also “send someone to just come see if I was home.” And then, at prosecutor Emily Johnson’s direction, Ventura listed several names of security personnel and personal assistants she remembered.

Johnson responded, “And we’ll get back to some of those folks.” This ex-lawyer is eager to hear more about them.