I had a whole metaphor lined up to open this essay about democracy's needing a ritual sacrifice to survive, but there's no time to be coy about this. Now that the Democrats have control of the Senate, they need to strike a final blow against one of the last and greatest obstacles to Congress' success: the filibuster.

President Joe Biden's agenda has at most two years before Republican obstructionism rears its head again, I argued Wednesday. But those two years can — and will — be neutralized if the Republican Senate minority is allowed to filibuster every bill that comes up.

Ditching the filibuster might be one of the only things former presidents Donald Trump and Barack Obama have agreed on. In 2017, Trump, new to the struggles of governing, repeatedly called for its abolition, inadvertently causing a stampede of support for it. Obama, a recent convert to the cause after leaving office, called the tactic a "Jim Crow relic" last summer during his powerful eulogy for Rep. John Lewis, the civil rights icon.

And yet it still lives on, despite having been whittled away at over the last decade. As it stands, some legislation still requires 60 senators' support before it can come to a vote. It's untenable as it currently exists — and yet, it still has its defenders on both sides of the aisle.

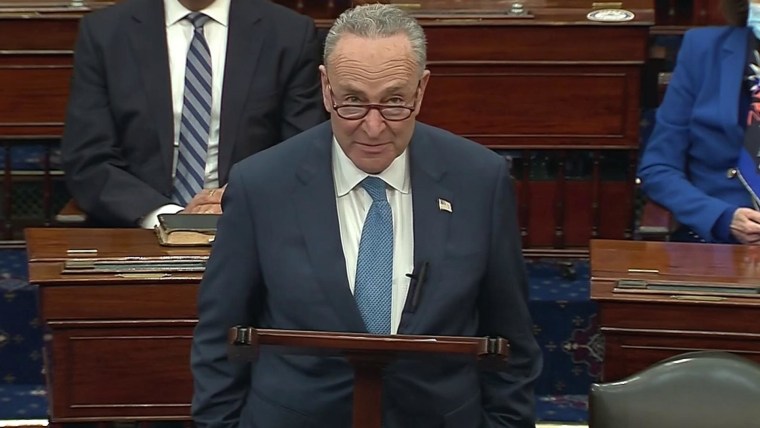

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., put it well when he was chair of the Rules Committee in 2010: "The truth is both parties have a love-hate relationship with the filibuster, depending on if you are in the majority or the minority at the time. But this is not healthy for the Senate as an institution."

The filibuster is an invention of a time when slaveholding Southern senators sought to turn their minority into a weapon.

It's a trend that has only gotten worse as the filibuster has been mythologized as a core privilege of the Senate. But legislation's needing support from 60 senators to come to a vote isn't in the Constitution. Nowhere in the Federalist Papers is that formula laid out — the framers required two-thirds majorities to ratify treaties, not to vote on bills.

Instead, the filibuster is an invention of a time when slaveholding Southern senators sought to turn their minority into a weapon. It was a cause eagerly picked up, as Obama noted, by those same Southern states as they stymied civil rights legislation.

"Unlimited debate was a sacred principle only on civil rights; on the vanishingly rare occasion other issues faced filibusters, Southerners voted to end them," Adam Jentleson, author of "Kill Switch: The Rise of the Modern Senate and the Crippling of American Democracy," wrote in The New York Times. For a time, the main use of the filibuster was to kill off civil rights bills, only sparingly being deployed otherwise. Unanimous consent from all 100 senators was the general operating standard — it wasn't until after 1964 that cloture, the procedure to cut off debate, went from a rarity to a basic fact of life in the Senate.

The practice became an art form for Republicans under Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky. During the Obama years, McConnell impeded nominees and legislation left and right — he has the nickname "the Grim Reaper" for a reason. In the last Congress, McConnell's Senate was a chamber where House-passed bills went to die. Cloture was passed on legislation only a handful of times in those two years. Just last year, the Senate twice blocked votes on a House-passed Covid-19 stimulus package from coming to the floor, even though a majority clearly favored it.

Even political scientist Jonathan Bernstein, who is ostensibly in favor of keeping the filibuster, could see that McConnell has been the problem. "If Mr. McConnell really respected the filibuster, he would have used it a lot less when his party was in the minority — and when it was in the majority, he would have worked to restore the rule rather than eliminating even more protections for Senate minorities," Bernstein wrote in a 2019 op-ed in The New York Times.

Unfortunately, the Senate Democratic Caucus, with its bare majority, isn't exactly united on this front. While several Democratic senators have voiced hesitance about killing the filibuster, Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia has gone ahead and named himself its stalwart protector.

"If you've got to blow up the Senate to do the right thing, then we've got the wrong people in the Senate, or we have people that won't talk to each other," Manchin told The New York Times in November while promising that he wouldn't be the 50th vote to end the practice.

Well, Manchin is right, although not in the way he likely meant: We've got the wrong people in the Senate. The number of senators who have been willing in recent years to advance legislation even if it's doomed to fail in an up-or-down vote has been paltry, judging by the number of cloture votes that have gone down in flames. And the result hasn't been new compromises forged from the ashes of those votes.

Still, despite having been right there in the Senate and witnessing the effects of the filibuster, Manchin wants to hold on to the supermajority rule. "I thought we should be working together. It should take a minimum of 60," Manchin told Fox News. "And that means you're going to have to have a few Democrats or Republicans, depending on who's in the majority, to work together. That's what we're all about. Why would you break that down, and there's no need to have the Senate?"

The gridlock that the Senate has imposed on Washington hasn’t given more power to moderates; it has inflamed the partisans who demand victory, be it total or Pyrrhic.

The answer is that the point of the Senate wasn't to protect the minority party — it was to protect the minority population in relation to the smaller states' grappling with the larger states. In effect, the Senate is antidemocratic by nature — why make it worse by allowing the filibuster to stand?

A number of solutions would still let the minority have a voice: Drop the threshold for cloture to 51 absent an actual "talking filibuster," in which a senator refuses to yield the floor; make cloture a majority vote but increase the time between cloture and a vote on the bill back up from two hours to 30 to allow time for amendments; make it so that majority leaders have less of an iron grip on the Senate's schedule, granting members of the minority the chance to introduce bills and amendments again. Any of these prospects would work better than the mess we have now.

And it is a mess, one that is helping erode Americans' faith in their lawmaking institutions even as the defenders of the status quo protect one institution's dangerous privilege. The gridlock that the Senate has imposed on Washington hasn't given more power to moderates; it has inflamed the partisans who demand victory, be it total or Pyrrhic.

Schumer needs to partner with Biden to move fast, leaning on his caucus to amend the rules now rather than burning time off the clock. One of the first bills the Senate is set to consider is one to expand voting rights and otherwise shore up democracy. Imagine the irony if Democrats allow that bill to stall not because it lacks the majority's support but because of the threat of a filibuster.