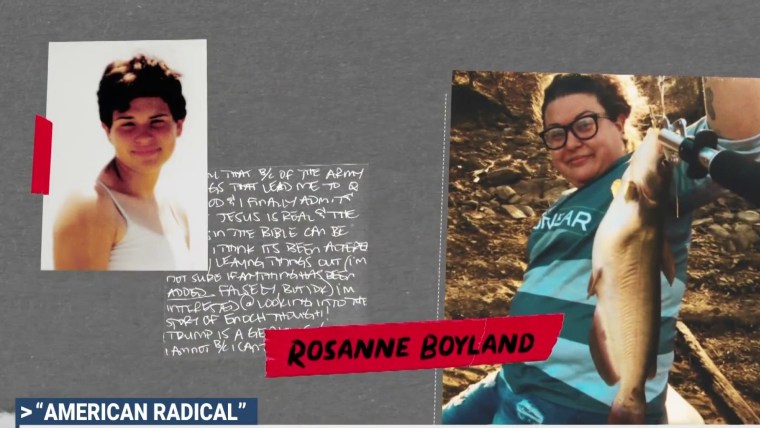

Three days after the Capitol riots on Jan. 6, I received a message from an old high school friend. The message read: “Ayman, I am sure you have seen the news. I made a public statement about the death of my sister-in-law Rosanne Boyland from Kennesaw who died on Wed. at the Capitol. My wife and I believe she was radicalized in a very short time inside of 6 months [...] would you be willing to hear her story?”

I had never imagined that what I had spent a decade covering overseas would bring me back to my hometown in Georgia to report.

My immediate reaction was shock. I had been intensely covering the insurrection on the air as part of our wall-to-wall coverage on MSNBC, but I had not yet connected the dots of who Rosanne Boyland was, nor where she was from. Soon after I reconnected with my friend who initially messaged me, Justin Cave, I would learn that not only did Boyland grow up in my hometown but that we had also attended the same high school a few years apart.

I was also surprised that Cave had used the word “radicalized” to describe the transformation his sister-in-law had undergone. Boyland was not a political person. She avoided crowds, and before last year she had never voted in an election. So how did she go from that to becoming a foot soldier in a movement that threatened the very essence of American democracy?

As I would learn, everything Boyland would come to believe — her fervent convictions about Donald Trump and QAnon, which drove her to fight and die at the Capitol that day — she had come to believe in just a few short months before her death, according to her family.

Before I became an MSNBC anchor, I was a foreign correspondent for NBC News and other news organizations based overseas. My career had been defined by the Sept. 11 attacks and the subsequent “war on terror.” I had spent more than a decade covering radicalism and extremism. I had seen firsthand how families lost their loved ones to fanatical ideologies and a false sense of purpose or belonging. But I had never imagined that what I had spent a decade covering overseas would bring me back to my hometown in Georgia to report.

As I began to investigate the circumstances around Boyland’s death at the Capitol for my new MSNBC podcast, American Radical, I quickly recognized a set of common characteristics. It was a similar pattern I had seen in cases I had reported overseas, and it revolved around what I call the Three D’s of radicalism: disinformation, destitution and demagoguery. Boyland’s case had the hallmarks of all three.

First, Boyland had experienced hardship in her life. By a young age, she had spent years struggling with a drug addiction. She had multiple run-ins with the law and was in and out of prison for drug-related offenses. She had suffered in physically abusive relationships. She struggled with her body image, which eroded her self-confidence. Tattooed across her chest were the words “beautiful disaster.” And above all, she lacked a sense of purpose and belonging in life.

Above all, she lacked a sense of purpose and belonging in life.

Although she had a close-knit family and a handful of friends, her relationships were strained during the years she was not sober. After she was diagnosed with cervical cancer, Boyland was unable to bear children. But after she became an aunt, she was able to give her life a newfound purpose, a commitment to helping and loving her two nieces. It motivated her to stay sober, according to her family. But because she could not bear children of her own, it would also make her vulnerable to a conspiratorial ideology built around “saving the children.”

Disinformation is a major problem in radicalism. When you can no longer differentiate between what is reality or truth and what is conspiracy or false, you become susceptible to manipulation. And Boyland had gone down some serious rabbit holes of disinformation, watching hours of videos, including some about the Wayfair conspiracy, and following hashtags like “save the children.” Believers of this theory subscribe to the idea that the e-commerce home goods site Wayfair was trafficking children to pedophiles under the guise of transporting and selling furniture. I know it sounds ridiculous. But it was precisely this type of theory that hooked Boyland and kept her glued to her screen for hours on end. Hashtags that were popularized and used by other Q believers made it easier to find more videos and content that perpetuated even more extreme theories and conspiracies.

When we analyzed scores of Boyland’s messages and social media posts, a clear pattern emerged. She was devouring memes, videos and posts about the alleged pedophilia ring taking over the country.

When we analyzed scores of Boyland’s messages and social media posts, a clear pattern emerged. She was devouring memes, videos and posts about the alleged pedophilia ring taking over the country. Even more troubling was that she was sharing them at an alarming rate. When those in her life confronted her or questioned or challenged her beliefs, she would become combative and withdrawn. It forced those who cared about her to either disengage and cut her out or turn a blind eye to her self-destructive behavior.

Overseas, disinformation in the Middle East was how the Islamic State terrorist group recruited more and more young fighters. It spread false information about who is to blame for a country’s societal ills. It would make its recruits believe that it was right and everyone else was wrong. It would manipulate religion to make its followers believe that its word or interpretation was the only truth to which they should devote themselves entirely. Q believers like Boyland were no different.

What is relatively new in America, and what has taken disenfranchised and misinformed people to the next level in the radicalism process, is demagoguery jacked up by social media. In the Middle East, the demagogues were usually the leaders of terrorist organizations who would feed young recruits solutions for their societal ills. If they joined the fight, they would be able to liberate their lands. If they were more religious and devoted, they would fight off the infidels. In America, demagoguery was rare and much more localized — until Trump came along and used the power of social media and the pulpit of the White House to reach millions of disenfranchised people without any filters.

To some extent, and to his followers, Trump was a demagogue. He sought the support of the masses by appealing to their desires, playing on their fears, exploiting their vulnerabilities. He made them believe that if they followed him, they could protect their country, stop the certification and steal the election. He made them believe they needed to do this or they would lose everything they cherished in their country — their freedoms, religions, rights. He made them foot soldiers in his warped, craven, extremist, anti-democratic ideology. And those who had believed, like Boyland — who had written in her journal that “Donald Trump is a genius” — followed him to the tragic end.

The question now is what should we do about it as a society? And how do we stop it from happening? Well, the short answer must be to limit all three of the D’s I mentioned. Find ways to slow the spread of misinformation and disinformation, improve the quality of people’s lives so they are not disenfranchised or destitute, and ensure that the rise of authoritarian demagogues is not easily able to recruit society’s most vulnerable and susceptible. Until we can mitigate these three, I fear we will continue to see radicalism take root in American society, as I have seen overseas.