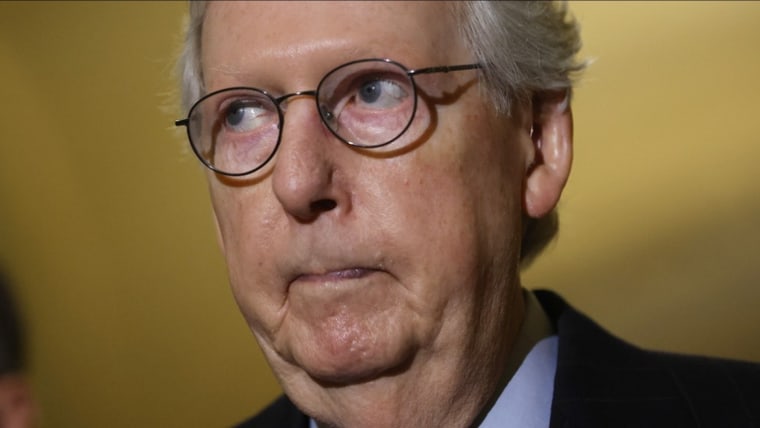

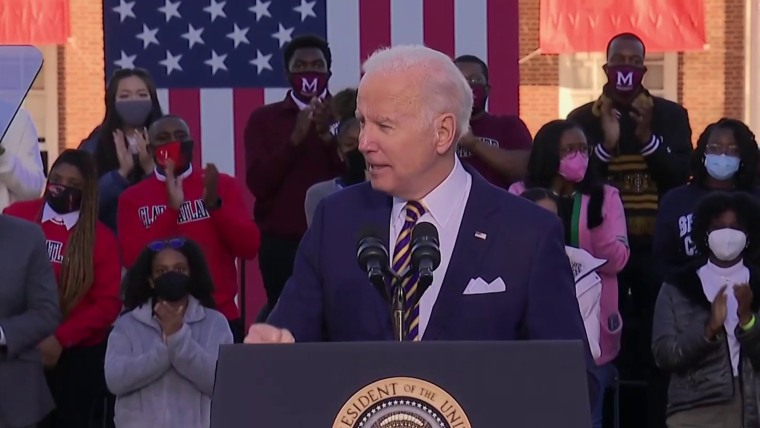

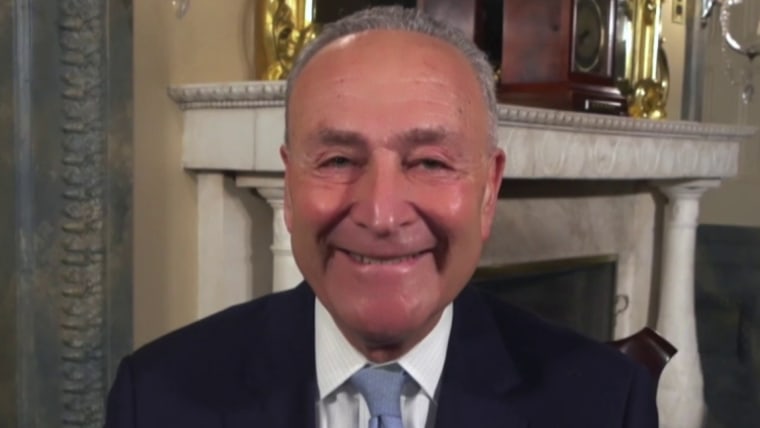

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., has now repeatedly threatened harsh consequences if Democrats change the filibuster rule and allow bills to pass the Senate with a simple majority vote. Taking direct aim at Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., McConnell on Tuesday painted a dire picture of what that future would look like if Republican senators and the voters they represent were cut out of the loop.

Hard as it may seem to believe, there are ways the already lethargic, dysfunctional Senate could be made even slower and more frustrating,

"If my colleague tries to break the Senate to silence those millions of Americans, we will make their voices heard in this chamber in ways that are more inconvenient for the majority and this White House than what anybody has seen in living memory,” McConnell said on the Senate floor.

The threat was an echo of McConnell’s 2021 promise to facilitate “a completely scorched-earth Senate” should the legislative filibuster be removed or altered. Hard as it may seem to believe, there are ways the already lethargic, dysfunctional Senate could be made even slower and more frustrating to both its members and a public that expects it to pass legislation. The question is whether McConnell would be willing to put in the effort to drastically raise the cost of doing business.

Denying Schumer’s unanimous consent requests would be the most obvious way for Republicans to punish Democrats for daring to bolster voting rights. Such agreements basically operate on the assumption that all 100 senators are totally fine with whatever action is being proposed, no vote needed. The most basic unanimous consent agreement can be used to insert items into the Congressional Record; the most complicated can line up weeks’ worth of legislative action in the time it takes to read out the agreement.

The Senate historian’s office told me via email that neither it nor the Senate Library is aware of a source that routinely tracks unanimous consent requests. But a search of the Congressional Record for Monday yielded at least 14 examples of requests for unanimous consent in the Senate. A closer look at the Senate’s record showed that the words “I ask unanimous consent” were used 16 times that day. (All of those requests, save one, were granted.)

Each request can free up hours of the Senate’s time. For example, here’s the request that Schumer laid out Monday evening to set up the next day’s schedule. By my count, it included at least five items that otherwise would have required a vote from senators to complete:

Madam President, finally, I ask unanimous consent that when the Senate completes its business today, it recess until 11 a.m., Tuesday, January 11; that following the prayer and pledge, the Journal of proceedings be approved to date, the time for the two leaders be reserved for their use later in the day, and morning business be closed; that upon the conclusion of morning business, the Senate proceed to executive session to resume consideration of the Davidson nomination postcloture; that the Senate recess from 12:30 p.m. until 2:15 p.m. to allow for the weekly caucus meetings; further, that all postcloture time on the Davidson nomination expire at 2:20 p.m. and that the Senate vote on the confirmation of the nomination; finally, that if any nominations are confirmed during today’s session, the motion to reconsider be considered made and laid upon the table with no intervening action or debate.

Republicans could also force Democrats to maintain a quorum on the Senate floor for any business to be conducted. The Constitution says a majority of senators needs to be present to conduct business, but the rules are a bit more lenient. Instead, the chamber acts on the assumption that enough people are there — even if there are clearly only five senators hanging around the floor.

Instead, senators routinely “suggest the absence of a quorum” to buy time between speeches, allow for informal haggling and allow members to get from their offices to the floor. The clerk very slowly calls the roll but is usually cut off via unanimous consent before reaching the end of their list. If a quorum is determined to be absent, though, all business halts until at least 51 senators are present and respond to the clerk’s call.

In the hellscape McConnell is describing, Democrats would have to cast endless votes on everything from when the session should begin to whether or not the clerks can skip reading the entirety of bills out loud to whether a newspaper article can be entered into the official proceedings. And with Democrats holding the slimmest of majorities, McConnell could keep enough Republicans off the floor to cause a total shutdown of business until enough Democrats were present to prove a quorum was present.

McConnell could make good on his threats “for a short term,” Faiz Shakir, former senior adviser to former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., told me Tuesday. After Democrats changed the filibuster rules in 2013 to allow presidential nominees to pass with a majority, McConnell forced several early morning and late-night votes, Shakir said. Eventually, though, things returned more or less to normal, albeit with more filibusters of judicial nominations to overcome.

“The question is how long you would maintain that kind of a strategy,” Shakir continued. “If he felt like it was behooving Republicans to be in this kind of protracted fight on the Senate floor over Senate procedures, he would continue to do it. … He would love to drag the Senate into doing nothing, which is his own preferred path.”

But the kind of filibuster reform in question could affect how McConnell responds, Shakir added. Yes, corralling all the Democrats for basic housekeeping would be annoying — but if instead of a flat 60 votes, three-fifths of senators present and voting could end a filibuster, the dynamic would make things more difficult for Republicans.

“If that were the case, McConnell is the one needing to make sure he’s got the numbers and preventing people from taking flights,” Shakir said. “That’s one of the values of that reform. So, if you wanna be the guardian of gridlock, as he’s positioned himself, you have to find the people to do it with you instead of being able to do it silently.”

For now, though, this is all academic: While Schumer has promised a vote as soon as Wednesday on potential filibuster reform, he’s still got at least two members of his own party who aren’t on board. But he seems more than willing to call McConnell’s bluffs.

McConnell on Monday said if the filibuster rule changed, his caucus would force votes on 18 bills on matters like fracking bans and ending Covid-19 vaccine mandates. GOP aides told The Wall Street Journal the “threat is intended to cause heartburn for Democrats.” In a not-great sign for their strategy, though, that didn’t exactly work out as planned.

Schumer called McConnell’s bluff by responding: “Well, we Democrats aren't afraid of these votes, so what I propose to the Republican leader is that the Senate hold up-or-down votes at a majority threshold on each of the Republican bills he has outlined tonight, as well as the Freedom to Vote Act and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act.”

To drive home the point, Schumer then asked for unanimous consent to move forward on the bills McConnell had just threatened to embarrass Democrats with — and the two voting rights bills.

McConnell, faced with the chance to deliver on his bluster, objected.