As someone born just four months before the Roe v. Wade decision, I’m sometimes tormented by the idea that we’ve made absolutely no progress in reproductive health over the course of my life. Just this week, Oklahoma passed a bill that will ban abortion from the moment of “fertilization.” Ahead of Georgia’s GOP Senate primary on Tuesday, front-runner Herschel Walker has made it clear there should be “no exception” to abortion bans in his state. News of criminalizing medically necessary abortions and even miscarriages of unknown cause makes this a bleak and frightening time.

I’ve been reminded by those deep in abortion work that there are in fact key differences between now and that pre-Roe time

But I’ve been reminded by those deep in abortion work that there are in fact key differences between now and that pre-Roe time, including numerous ways our language and frameworks could be more supportive of those facing an unplanned pregnancy and more expansive in our vision of reproductive health. In that spirit, I’m proposing four ways we can modify our conversations around abortion:

We should acknowledge the many ways we are in fact in a better place than we were in 1972.

Over the past five decades, contraceptive options have expanded well beyond the pill or spermicide and include long-acting, passive methods such as IUDs and implants. Though still requiring a prescription, a handful of states allow pharmacists to prescribe, and access to online prescribers has been increasing. There is also emergency contraception, which can be taken shortly after unprotected sex to prevent the pregnancy from occurring. Under the Affordable Care Act, many insurance plans must cover contraception and counseling, increasing their accessibility.

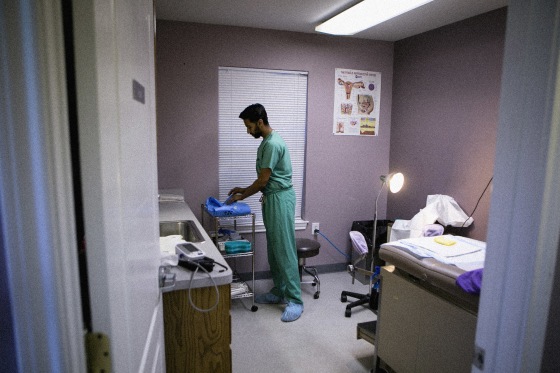

Over-the-counter home pregnancy kits became available in 1977, so the diagnosis of pregnancy no longer required a doctor’s visit, could be made earlier, and set the stage for effective use of medications for abortions. Although coat hanger imagery has cropped up everywhere on social media, half of early abortions occur via medication now, moving abortions out of clinics and into homes. Abortion medications can also be prescribed via telehealth in some states.

The internet provides readily accessible information about all aspects of reproductive health, including information about sexual health, pregnancy testing, choosing a type of contraception and abortion options across all 50 states. Social media means that young people can connect to others with similar experiences and questions, which creates the potential to be less isolated, and that they have access to expert recommendations as well. Acceptability, stigma and norms have changed, too: Sixty-seven percent of U.S. adults under the age of 30 believe that abortion should be legal in all or most cases. There’s plenty to worry about. But progress since the ‘70s should give us hope, too.

Include an emphasis on the immediate and the local in our conversations.

Online dialogue has been dominated by discussion of marches, protests, voting and political strategy — all critical actions for abortion access long term. But there is so much action to take in parallel that addresses people’s needs immediately.

Local abortion organizations have been doing the work of providing reproductive services steadily, constantly, wisely, navigating constantly changing political and legal landscapes before and since Roe. It takes a matter of minutes to look them up, sign up as a volunteer, join their listservs and donate. Supporting them is an immediate and direct way to translate concern into action. Independent abortion clinics may operate in hostile environments and support must be robust to counterbalance what they have to endure. There is no need to announce one’s self or offer new ideas — they’ve been doing this for a long time and have created ways for people to join in. (In fact, nothing is more outrageously disrespectful than suggesting something in a void of experience and historical understanding, such as the calls last year for an “underground railroad” for abortions, which overlooked existing Black-led abortion work while co-opting an earlier Black-led movement.)

On a more individual level, I’ve been thinking of all the young people I’ve seen in the emergency department over the years, overwhelmed by the news of an unexpected pregnancy. Some struggle to identify a single person they feel confident they can call to support them.

The popular slogan for abortion, “my body, my choice,” along with other slogans focused on personal rights, tap into the American desire for autonomy in all things. But individual choice has been a limiting message on a number of fronts.

Do the young people in your life know their options? Are they empowered to seek birth control, to access pregnancy testing, to talk through decisions around carrying a pregnancy, raising a child, or seeking an abortion? Do they know the costs of all these things and do they have a financial plan? Do they know they can trust you to have conversations about these things and to call if the unanticipated happens?

An unexpected pregnancy can turn someone’s life upside down, and requires psychological and material support, information, transportation and funds. Anyone — aunts, uncles, cousins, godparents, neighbors, teachers and others — can provide some or all of these things, singly or as part of a support network. We cannot leave those of reproductive age to fend for themselves right now, especially in an increasingly complex medicolegal environment.

We need to shift to a broader reproductive justice frame.

The popular slogan for abortion, “my body, my choice,” along with other slogans focused on personal rights, tap into the American desire for autonomy in all things. But individual choice has been a limiting message on a number of fronts. It risks encouraging people to secure their own rights, in their own states, and then give up the fight. An emphasis on choice assumes that once one is legally free to decide, the resources and access are the same; but full access to reproductive services is also a function of the inequitable systems and structures that we have built. After all, even with Roe in place, numerous barriers continue to exist, especially for women of color, those living in poverty, in rural areas, and in states with high restrictions on abortion. The urgency of this moment cannot be so narrowly defined as to secure one’s own choice, or even women’s choice, in this single matter.

Dr. Joia Crear-Perry, the founder and president of the National Birth Equity Collaborative, reminds me that Roe has a fundamental belief structure — one of which is who has agency over another’s body — that must be repudiated. Power over bodies has a long history that is inclusive of racism, classism and ableism. And what these systems have in common is more sweeping and diabolical than control over reproductive decisions: It is about the dominance of one set of humans over another.

“What we’re seeing is belief in a hierarchy until it became codified into laws,” Crear-Perry told me. “But what if the belief was never real? We need to reinforce the belief that we are all important … then codify that.”

This is of course, the concept of reproductive justice. And it is empowering for a number of reasons. It assures “not only a woman’s right not to have a child, but also the right to have children and to raise them with dignity in safe, healthy and supportive environments,” in the words of the scholar and social justice advocate Dorothy Roberts. If anti-abortion advocates are criticized for not caring about any aspect of a child except for fetal viability, reproductive justice corrects this orientation. Rather than fetishizing a clump of cells, it recognizes the whole person over the course of their lives, and their fundamental right to pursue a thriving life, liberty and happiness. As a Black woman, “[w]hen do I get to be viable?” asks Crear-Perry. Our society must contend with its failure to recognize the viability of all those already in its midst.

Stop trotting out only our scariest abortion stories.

Stories of denied, delayed or concealed abortions resulting in sickness, trauma and death flood social media whenever abortion is legally at risk. Such stories have purpose: They underscore that limiting abortion access drives up higher-risk abortions, that rational medical care is sometime derailed by abortion restrictions, and that it can be difficult for systems and people to navigate legal liability, even in the context of undeniable medical emergencies. The stories can inspire empathy and action. Indeed, the tragic death of Savita Halappanavarr due to sepsis after denial of abortion was a galvanizing event in Ireland’s abortion campaign.

But the imagery comes with some dangers as well. Because many of the stories are about ectopics, pregnancy after rape or septic abortions, it may seem to advocate for carve-outs for the particular circumstances of the stories, rather than universal abortion access. It may neglect an important health message, which is that the vast majority of abortions in the U.S. are timely and safe (with a lower complication rate than common procedures like wisdom tooth extraction or an appendectomy) — a message that is much needed, as only half of Americans polled feel that abortions are “very safe” and the majority are misinformed about when abortions occur. And although the normal, boring abortion story isn’t exciting, it should be mentioned often enough to be our familiar referent standard: A person sought care, they received care, they did well.

As the battle over abortion roils on, it’s worth keeping in mind that how we speak about topics has tremendous power to shape how we think about them, and subsequently, how we are inspired to act.