Last Friday, the Alabama Supreme Court became the first in the nation to recognize frozen embryos as legal persons. The court’s decision — in a case in which three couples sued a fertility clinic for wrongful death after a patient destroyed several embryos — has already led the University of Alabama Birmingham, the state’s largest health care system, to pause IVF procedures. But what is happening in Alabama is just the beginning. This decision will affect the millions of people who become pregnant each year, their families, and their health care providers.

To anyone who closely read Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the Supreme Court decision that ended the constitutional right to abortion almost two years ago, the Alabama decision should not come as a shock. The majority opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito and joined by most of his conservative colleagues, repeatedly referenced the “unborn human being” — echoing the language of conservative Mississippi lawmakers. Furthermore, the majority declared that the state has a legitimate interest in the “preservation of prenatal life at all stages of development,“ without regard to whether that life exists in utero or not.

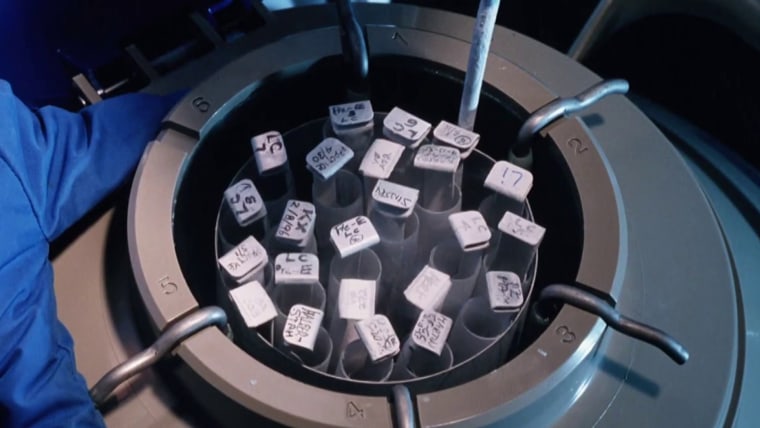

That language cleared the way for states to treat fetuses at any state of development as legal persons. That includes embryos created by in vitro fertilization, the reproductive technology through which 2% of children in the U.S. are born each year. As a result of IVF, there are as many as 1.5 million frozen embryos in the country. The Alabama decision might mean that some of these embryos need to remain frozen forever — at least until someone uses them. Otherwise, anyone who destroys the embryos or even uses them for research could face claims for wrongful death and be liable for millions of dollars in damages. Of course, that assumes that anyone will be willing to offer infertility services in Alabama in the first place: doctors at UAB expressed fears of facing criminal charges if they inadvertently destroy an embryo.

The fallout from the Alabama decision will likely be felt well beyond its borders. A number of states already have broad personhood language, some of which could apply to the destruction of frozen embryos. Louisiana, for example, defines IVF-created embryos as juridical persons. Arizona has a broad law, currently tied up in court, declaring any fertilized egg to be an embryo.

Though anti-abortion forces have fought for the personhood of fetuses and embryos since the 1960s, since Dobbs the personhood movement has gained greater prominence and ambitions. Last year, abortion opponents celebrating the anniversary of Roe’s reversal demanded the recognition of personhood under the U.S. Constitution. And as the Alabama ruling shows, the concept of the fetus or embryo as a person is becoming more accepted at the state level.

Personhood puts the interests of fetuses above those of the parents. While more than half of the states have statutes allowing wrongful death claims for fetuses, 15 of them, including Alabama, allow such claims at any stage of development. Only some explicitly exempt the mother from being sued. Florida is currently considering a wrongful death bill that would allow damages, even if the fetus could not survive on its own (the bill would not allow claims brought when an embryo is outside the uterus). On the criminal side, the concept of fetal personhood already exists. More than half of the states criminalize the killing of a fetus, embryo or zygote as feticide or homicide. Only some exempt the pregnant person from prosecution.

But the Alabama ruling opens up new civil and criminal liabilities of all kinds, including for damage to embryos in transport, in the lab or in the clinic. Even individuals who discard their embryos or donate them to research could risk facing liability for wrongful deaths. And if IVF embryos are deemed children, their storage or cryopreservation could be treated as child abuse. Even if these legal minefields are somehow navigated, there are the added expenses of insurance coverage for health care providers.

Increasingly, since the Dobbs ruling, states like Alabama put a high price tag on pursuing justice for reproductive harms. While the unintentional destruction of embryos that occurred in this case was well-suited to some sort of legal remedy, it seems perverse to choose between a punitive vision of fetal rights and restitution for those grieving the loss of potential parenthood. There are remedies that don’t go all the way to personhood. Even in the Alabama case, the plaintiffs had other claims unrelated to personhood. Others have claimed breach of contract, malpractice, and even loss of the right to become a parent.

Instead, the state court turned a case about three couples’ grief into an opportunity to proclaim the close relationship between Christianity and state constitutional law — and to advance an idea of personhood that so-called abolitionists in the anti-abortion movement argue requires the punishment of women themselves. Strikingly absent from the court’s decision, however, is a meaningful discussion of what the decision means for those who seek to become parents – or for those who don’t. But though the court ignored those consequences, that doesn’t mean they don’t exist. The dangers of the Alabama ruling go far beyond its implications for IVF. It’s clear that as much as the court discusses personhood, not everyone’s will count.