After Republicans lost to Barack Obama in 2008, the tea party — a combative conservative grassroots movement — came together almost overnight, primaried establishment Republicans and remade the party. Today, Democrats on Capitol Hill are feeling pressure from their base. Angry Democratic voters are flooding town halls held by lawmakers of both parties. Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez pack stadiums at their “Stop the Oligarchy” rallies. The first notable progressive primary challenger of 2026, Kat Abughazaleh, raised $200,000 on her first day in the race. And headline after headline is calling this movement a “Democratic tea party.”

But the comparisons to the tea party are mistaken. Democratic leaders have a better relationship with their base than the GOP of 2009 did. If they play their cards right, they’ll end up with a retooling of the party — not a revolt.

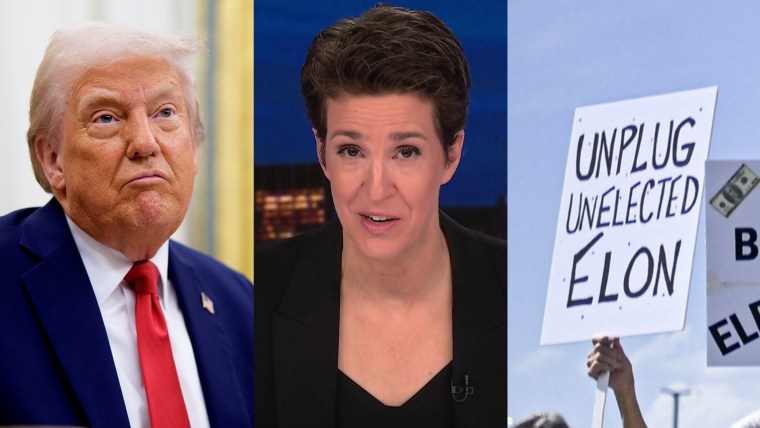

The base mostly wants a Democratic Party that will take the fight to Trump.

Establishment Republican leaders lost control of their party because they failed to serve their base. Though Republican voters wanted to see decreased immigration, GOP leaders pursued immigration reform in 2007 and 2013. Though less than a quarter of Republican primary voters wanted cuts to Medicare and Social Security, Republicans put Rep. Paul Ryan of Wisconsin, the party’s chief entitlement-cutter, on the 2012 presidential ticket. And though, as Republican pollster Patrick Ruffini wrote, the Republican base wanted “maximum confrontation” on culture war issues, GOP leaders (prior to Trump) frequently pursued more of a tactical retreat.

Today’s Democrats have a better relationship with their base. There’s no issue like immigration or entitlement cuts, where elected leaders openly defy their voters’ clearly articulated wishes. Swing voters disagree with the scope of Democrats’ support for trans rights, and believe the party lacks credibility on immigration. But the base mostly wants a Democratic Party that will take the fight to Trump. And Democrats already have leaders, like Sanders and Ocasio-Cortez, who want to meet that need.

Another core feature of the tea party movement was that it fought the establishment everywhere. They challenged establishment Republicans in red and swing states, even when it cost the party winnable elections. Richard Mourdock, who beat the Republican incumbent, Richard Lugar, in Indiana’s 2012 GOP Senate primary, went on to say pregnancies due to rape were “something God intended” and lost the seat. In Delaware’s 2010 Senate election, establishment Republicans wanted to run former Gov. Mike Castle, but the tea party pushed a little-known and inexperienced candidate named Christine O’Donnell. She won the primary, but lost the general after declaring in a campaign ad “I am not a witch.” The list goes on.

Democrats have a healthier pattern: Experiment with insurgents in safe seats and nominate electable candidates in tough races.

The most famous progressive primary challengers — Reps. Ocasio-Cortez, Ayanna Pressley and Marie Newman — dethroned long-serving Democrats in safe blue seats. Abughazaleh, the first progressive primary challenger of the 2026 cycle, is running in a district Kamala Harris won by 37 percentage points. There was never any danger of these candidates losing to a Republican.

In swing states, Democrats coalesce around less progressive candidates. Rising stars like Josh Shapiro, Ruben Gallego, Elissa Slotkin, Mark Kelly and Gretchen Whitmer either ran unopposed or won their primary handily. Progressives haven’t made too much trouble in these races.

Some high-profile, aging Democratic leaders likely will face primary challenges. Some may lose.

There are exceptions to both these rules. The tea party backed some electable swing state candidates, like Marco Rubio, then a senator from Florida. Progressives and moderates end up in occasional fights, like the 2022 Senate primary between John Fetterman and Conor Lamb in Pennsylvania. But, in general, the Democratic insurgency is acting more strategically — and working more effectively with the establishment — than the tea party ever did.

The Democratic retooling might be painful — but it doesn’t look like a tea party yet. Leading Democrats won’t get out of this moment unscathed. Some high-profile, aging Democratic leaders likely will face primary challenges. Some may lose. But younger, savvier Democratic politicians will find ways to get more combative with the Trump administration — and stop a primary challenge before it materializes. And in 2028, Democratic presidential contenders will try to move on from the playbook of the Obama-Biden era and fashion a new strategy that more effectively leverages voter anger.

But a new approach is not a “tea party.” It’s a slightly-more-turbulent-than-usual reshuffle. And if Democrats can stay close to their voters — reflecting their values on the key issues, shedding unpopular positions, staying on top of potential new issues (e.g., job losses to AI) and satisfying the desire for fierce opposition to Trump — the party may come out of this tumult in good shape.