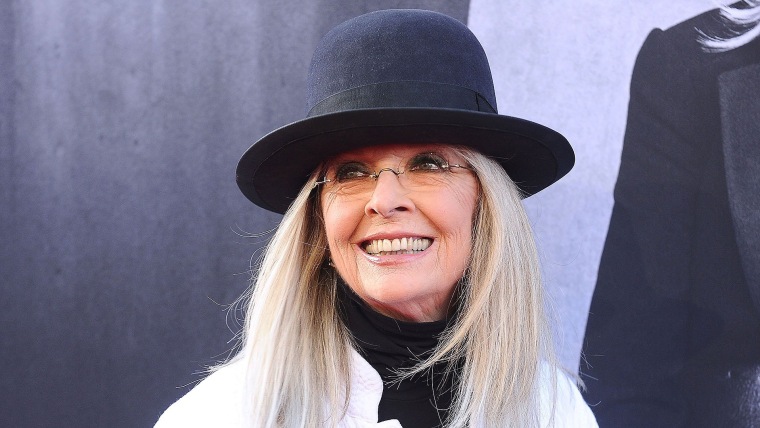

With the death of Diane Keaton, bona fide celebrity and A-list actor by every metric, it seems we have lost not just a beloved actor, but one of the few remaining celebrities with a true sense of self and a willingness to embrace individuality.

Regarded for her irreverence and self-deprecating charm, Keaton appeared in some 100 movies including Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Godfather” trilogy and Woody Allen’s “Annie Hall,” for which she won the 1977 Academy Award for best actress. Little is known about the cause or the exact date of Keaton’s death.

Keaton lived her life as she saw fit, eschewing the trappings of traditional womanhood and of Hollywood

Keaton lived her life as she saw fit, eschewing the trappings of traditional womanhood and of Hollywood for a quietly revolutionary femininity defined by freedom of self. Certainly, Keaton was not perfect, but throughout her career she remained genuinely herself.

In a sweeping 2019 interview with People magazine, Keaton reflected on her life-long independence: “I’m 73 and I think I’m the only one in my generation, and maybe before, who has been a single woman all her life.” Keaton, who had several high-profile romances, including with legendary actors Warren Beatty and Al Pacino, Apple founder Steve Jobs, and controversial director Woody Allen, was unyielding about her decision not to marry. “I remember one day in high school, this guy came up to me and said, ‘One day you’re going to make a good wife […] and I thought, ‘I don’t want to be a wife. No.’”

When Keaton was well into her 50s, she adopted two children, a daughter Dexter, now 29, and son Duke, now 25. Of motherhood she said to Ladies’ Home Journal in 2008, “[it] was not an urge I couldn’t resist. It was more like a thought I’d been thinking for a very long time. So, I plunged in.”

For many of us, certainly for me, Keaton’s legacy as a true original is best illustrated by her sense of style. She is antithetical to the conventions of today’s celebrity dressing. Her style wasn’t born of brand deals, stylist’s vision, or capitalization of any trend, but of creative expression, self-understanding and willingness to experiment.

Keaton reflected on her style in writing twice: first in a 2014 collection of essays called “Let’s Just Say it Wasn’t Pretty” and a 2024 coffee table book called “Fashion First.” In both, Keaton addresses her own physical insecurities, the sort of armor — “an impenetrable fortress,” she writes — that clothing shielded her with, and a willingness to try and fail with self-expression. She explains that her style grew from Cary Grant’s famous postulation that the clothes make the man.

So distinct and intractable was Keaton’s personal style that it influenced the characters she played on screen. Allen famously asked Keaton to pick her own wardrobe in “Annie Hall.” After the movie’s release in the spring of 1977, The New York Times commented on its fashion influence with an article called “The Hall-Marks of the Annie Look,” noting it was “now popping up on the streets with amazing frequency.”

I think of her as the flawed matriarch in “The Family Stone,” one of my favorite Keaton films — in full skirts, pressed white tuxedo shirts, and a plot-symbolic onyx cocktail ring. I think of her standing between Goldie Hawn and Bette Midler in a mid-thigh and boxy white skirt suit performing Lesley Gore’s “You Don’t Own Me” at the end of “The First Wives Club.” I think of her flawlessly delivering a monologue about motherhood and letting go to Lauren Graham and Mandy Moore in “Because I Said So,” wearing a breathtaking multistrand pearl necklace over a tailored black top.

Keaton has left us at a time when we really need her. American culture is dominated by conformity, entertainment feels unoriginal and uninspiring, and fashion is woefully propelled by trend. Attention is the driving force and money is the goal. Some have argued, with little convincing needed for me, that we’ve entered something of a cultural dark age.

In Keaton’s own words, she was “hardly iconic.” I will have to disagree with her there.