This article is the first in a five-part series called “Protecting the Election.” As former President Donald Trump and many of his allies refuse to concede his defeat in the 2020 election, this MSNBC Daily series brings election law and policy experts to explore the many threats to certifying election results at both the state and national level.

Normally, the period after an American presidential election is a time for cooling off and winding down tensions, and is often a bit of a political “honeymoon” for the winner. But as in so many things, we are not living in an era of electoral normalcy.

Luckily, we do have some new guardrails, enacted in response to the attempts to overturn the 2020 election. The Electoral Count Reform Act (ECRA), signed into law in 2022, updates and shores up many of the antiquated procedures from the old Electoral Count Act of 1887, which proved so unhelpful in 2020. The 2024 election will be ECRA’s first test, and it may well be a trial by fire. And unlike the 2020 election, the stress test might come from both sides of the aisle.

The Electoral Count Reform Act updates and shores up many of the antiquated procedures from the old Electoral Count Act of 1887.

In deciding a possible dispute over the most powerful office in the world, the rule of law is paramount. The process of an American presidential election is intricate and complex, with thousands of state and federal officials having a role in the final outcome. But the legal parameters of how any potential disputes will play out are reasonably clear and worth reviewing in advance.

When is Election Day?

The first question answered by ECRA is deceptively simple: When is Election Day? As is tradition, this date remains set at the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November, which this year is Nov. 5. But as hurricanes and their aftermath continue to batter states in the Southeast, the question of an election-disrupting emergency is not entirely hypothetical. The same issue arises from the possibility of a terrorist attack, mass shooting or other disruption to polling places on Election Day. ECRA provides an answer for how such emergencies can be fairly and lawfully handled.

Under the newly reformed federal law, Election Day is defined as the usual date, except that voting may be extended “as necessitated by force majeure events that are extraordinary and catastrophic.” By qualifying election emergencies in this manner, ECRA makes clear that litigation or other legal disputes over a state’s administration of the election do not qualify. (Using force majeure in this manner was a particular suggestion I’d advocated during ECRA’s drafting). Only events outside of the state’s control, such as a natural disaster, are sufficient to extend the deadline otherwise set according to Congress’ constitutional power to determine the “time of choosing electors.”

As with most other matters under ECRA, states must apply their election laws as they stood on Election Day, with no later alterations permitted, such as by the legislature convened in a special session. In each state, a possible emergency invocation of these extended voting procedures is assigned to a designated official, who may be the governor, secretary of state or a state elections board. This rule also forecloses the idea, advocated by some during the 2020 election, of state legislatures or other officials attempting to overturn the results of the state’s popular vote.

Counting the votes

The next step in the process is the counting of votes and the ascertainment of a winner in each state. Here, ECRA provides a remedy intended to address problems not just from 2020 but also from the notorious 2000 election. Instead of the usual cumbersome procedure for federal litigation, where lawsuits must be filed first in a district court and then appealed to one of the circuit courts before finally reaching the Supreme Court, a special three-judge panel is provided, consisting of two circuit judges and one district judge. This court’s rulings are then directly appealable to the Supreme Court, ensuring a prompt resolution of both legitimate legal objections and possible rogue actions by state officials. If any state official refuses to comply, the courts are empowered to order another official to provide the necessary certifications.

It is this procedure that would come into play if, for example, a state’s governor refused to certify the properly chosen members of the Electoral College, or if a secretary of state refused to certify the popular vote totals on which that certification depends. The final “certificate of ascertainment” from each state naming its electors must be finalized no later than Dec. 11, six days before the Electoral College meets.

Once each state’s popular election result is finalized, the state then appoints its members of the Electoral College. These electors, nominated by each party in advance, meet in their respective state capitals on Dec. 17 to officially cast the votes that will actually determine who has won the election. In most states, as upheld by the Supreme Court in the 2020 ruling Chiafalo v. Washington, these electors are bound by state law to vote for their party’s nominees. The candidate who wins an absolute majority of the electoral votes, currently 270, thereby becomes the president-elect.

Changes to congressional certification

The next stage of the process comes when these votes are transmitted, as required by the 12th Amendment, to the president of the Senate, otherwise known as the vice president — currently Kamala Harris. She will not be the first vice president to preside over a certification of her own victory or defeat, a task previously carried out by Al Gore, Richard Nixon and George H.W. Bush, among others.

But contrary to theories rejected by then-Vice President Mike Pence in 2020, ECRA affirms that the vice president’s role is purely ceremonial and entails no discretion whatsoever. Instead, the limited range of possible disputes at the electoral count on Jan. 6 must be decided by Congress.

ECRA deliberately pushes most possible disputes over election results into the courts.

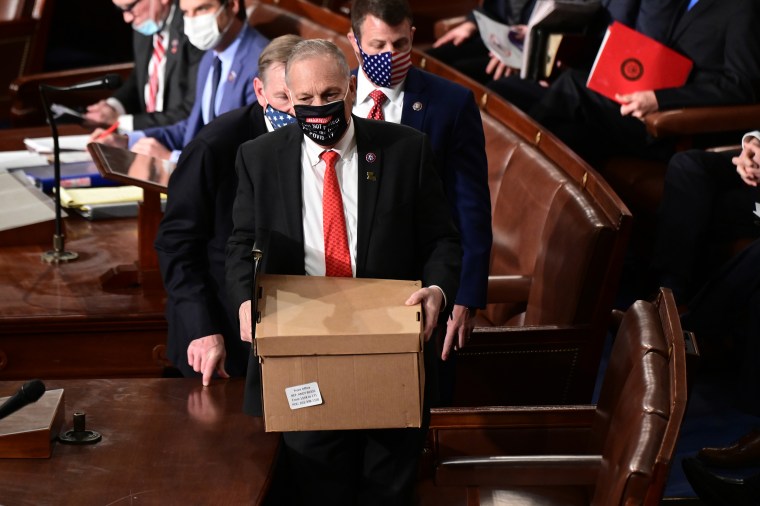

Here, ECRA makes an important change from the old Electoral Count Act. Previously, only one member of each house of Congress was required to object to electoral votes, sending the matter to a debate and vote. It was under this provision that some Republican members objected to the electoral votes for Joe Biden in 2020, a procedure interrupted by the attack on the Capitol.

Now, objections require the co-sponsorship of at least one-fifth of each house, or at least 87 representatives together with at least 20 senators. None of the objections attempted at the last electoral count would have cleared this threshold. Lacking enough support, frivolous objections will instead be gaveled down as out of order.

ECRA deliberately pushes most possible disputes over election results into the courts. In particular, objections to the identity of the proper electors based on who actually won each state’s popular vote are to be litigated in advance, with a definitive court ruling then binding on Congress. This would cover the objections advanced by Donald Trump supporters in the last election, which essentially alleged that the wrong slate of electors had been certified in several key swing states. No longer will Congress play any role in deciding between competing slates of supposed electors, and only one legitimate slate’s votes will be presented during the joint session.

Another set of objections remains within Congress’ purview, as required by the Constitution. These cover whether the votes by otherwise legitimate electors were improper, or in the legal term of art, “regularly given.” This would include, for example, a hypothetical objection to electors’ failure to cast their votes on the prescribed day, which the Constitution requires to be the same in every state. It would also cover, somewhat less hypothetically, an objection that the votes were cast for an ineligible presidential candidate.

It is on this point that objections from Democratic members of Congress are possible, on the basis that Trump is disqualified under Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, a provision adopted after the Civil War to bar oath-breaking insurrectionists.

Though the Supreme Court ruled earlier this year that states may not kick Trump off the ballot on this basis, the question of whether he is actually disqualified remains for Congress to decide. This objection might be raised to votes cast for him even if he has already lost, and would require majorities in both the House and Senate to sustain.

To the maximum degree consistent with the Constitution, ECRA sought to put electoral disputes into the courts rather than being decided by Congress.

Once Congress completes the electoral count on Jan. 6, the process is over and its results are final, except in the unlikely event that no candidate has won the necessary majority of 270 electoral votes. In this scenario, under the 12th Amendment, a “contingent election” would be held, with the House electing the president (under an unusual procedure where each state delegation casts one vote) and the Senate would choose the vice president.

To the maximum degree consistent with the Constitution, ECRA sought to put electoral disputes into the courts rather than being decided by Congress. Any arguments over which candidate, and thus which party’s slate of electors, has won a state’s popular vote is to be decided in federal court prior to when the Electoral College meets in December. In all cases, state law as it stands on Election Day is decisive, and states may not change the rules after the fact.

Congress, with the vice president presiding ceremonially but having no say in the matter, is empowered to address only a narrow set of questions about whether the otherwise valid electors have cast their votes in a permissible manner under the Constitution, such as for a candidate who is not a natural-born citizen or who is not at least 35 years old. But the role of Congress will not be to relitigate disputes over how each state conducted its election.

Once this process is complete — state laws implementing a popular election for members of the Electoral College, courts deciding any disputes over the outcome of those elections, the duly appointed electors meeting and casting their votes, and Congress counting the electoral votes — the winner will be sworn in at noon on Jan. 20, a date and time set in stone by the 20th Amendment.