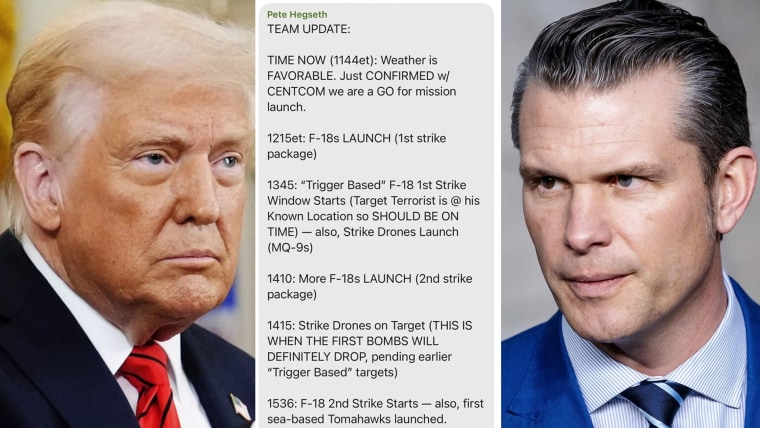

Nearly lost in last week’s wall-to-wall coverage of the Signal group chat security lapse was the role of a different kind of app, one at least as popular as Signal, in further revealing the flawed security protocols among some of the same, most highly targeted officials in our government. Reports showed that the Venmo accounts of Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth and national security adviser Mike Waltz, among others, were left public, revealing the officials’ personal contacts on the app.

Allowing your friends list to be public, let alone your actual transactions, makes it easier for adversaries to target you.

The digital payment application Venmo, which is owned by PayPal, is the third-ranked payment system among the 60% of Americans who use such apps to pay for purchases. Instead of pulling out our credit cards, over half of us pull out our phones, at least twice a week, and use a digital payment app. So do several of the senior participants in the Signal group chat involving the U.S. plan to attack Houthis in Yemen, apparently. But unlike the average person, the way they use it poses critical security risks and questions.

Following the Signal chat discovery, in addition to Hegseth and Waltz, the accounts of White House chief of staff Susie Wiles; Dan Katz, chief of staff at the Treasury Department; Joe Kent, chief of staff at the State Department; and Brian McCormack, a senior National Security Council staffer, were also revealed to be set to public. Last July, Wired magazine confirmed that Vice President JD Vance let his Venmo contact list default to public. Among his contacts were wealthy individuals who seem to qualify as the “elite” that Vance claims to disdain, and some of the authors of Project 2025. Vance didn’t comment on the Wired reporting at the time. Waltz and Wiles made their accounts private after they were contacted by Wired for comment last week. The Pentagon hasn’t commented on Hegseth’s Venmo account.

Venmo automatically adds your friends and contacts directly from your phone. This makes it easier to send a payment to someone you know or regularly do business with. Hegseth, or someone with access to his account, didn’t opt out of that feature. Another feature makes your contact list publicly viewable. Hegseth’s account allowed that, too, although it doesn’t mean his payment transactions were public (though in Venmo’s early days they would be). But McCormack’s transactions appear to have been public, as were Katz’s — which is why we know that Katz made a payment in 2018 accompanied solely by an eggplant emoji.

Venmo is different than many payment apps because of its dual social and financial nature and because it makes you take action to avoid having your contacts and transactions default to public. Venmo’s early strategy was to build trust and confidence with users by capitalizing on the comfort level of transacting business with friends, by importing users’ social media and phone contacts. You signed up for Venmo through your existing Facebook account. And, by making payment transactions public, and including a note feature to maybe show your buddies that you bought pizza for everyone, Venmo became a social media-like display of what your shopping, dining and partying looked like last weekend.

It was only after researchers found then-President Joe Biden’s public Venmo contacts (it took them 10 minutes) in 2021 that Venmo added the ability to make contact lists private. You can also now shield your transactions from public view.

Especially if you hold a high-security position, allowing your friends list to be public, let alone your actual transactions, makes it easier for adversaries to target you. It need not be a foreign intelligence service pursuing you for this to work. It doesn’t require much sophistication. Criminal organizations and solo hackers, armed with your contacts, can send you a spear phishing message using the recognizable email address or phone number of a friend and unleash malware into your device, including ransomware. Hackers can spend thousands of hours trying to find a phone number, email or name of a contact their target might accept a message from, click on an attachment in that message and become a victim. But hackers wouldn’t need to spend hours targeting these officials. Not with public contact and transaction lists.

A foreign intelligence service could wreak even more havoc. Their abilities include being able to entice you to click on an attachment, presumably sent by a friend, and install a beacon virus that receives hacker commands. They can covertly install logging software that documents every keystroke you enter while on your device. Maybe even the words you type in a sensitive group chat with colleagues.

Such data can also be a treasure trove for journalists and watchdog groups searching for conflicts of interest or professional biases.

Such data can also be a treasure trove for journalists and watchdog groups searching for conflicts of interest or professional biases. Hegseth’s contacts, for example, contain myriad wealthy individuals in the Silicon Valley tech industry, including Peter Thiel, who co-founded PayPal, as well as other CEOs who have large DOD contracts. Also listed were senior executives in health care. That might interest pundits wondering if the VA is already headed to privatizing veterans’ medical care.

If you are among Venmo’s millions of users, you may wonder about how to make your account safer. Thankfully, Venmo now offers options, and there are “how to” instructions across the internet, including one from The Washington Post.

The Signal group chat scandal and the Venmo accounts revelations aren’t isolated incidents. They reflect either a shocking lack of security awareness among many Trump Cabinet officials, or a reckless disregard for national security — or possibly both. Senior intelligence community leaders don’t need to be cybersecurity experts to protect their personal and professional lives from penetration. Each of their departments should have technical experts who can harden their bosses’ digital security immediately upon reporting for duty. Why that hasn’t happened should be the subject of congressional inquiry.

In a statement given to Wired in response to questions about the Waltz and Wiles accounts, a Venmo spokesperson said: “We take our customers’ privacy seriously, which is why we let customers choose their privacy settings on Venmo for both their individual payments and friends lists — and we make it incredibly simple for customers to make these private if they choose to do so.”

Incredibly simple for us? Maybe. Incredibly simple for members of the Trump administration? Apparently not.