Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton appears to be back in action. Her recent increased public visibility through fundraisers, television appearances and op-eds isn’t just a coincidence: As NBC News reports, Clinton is “stepping into a role as one of the most prominent and influential surrogates in Biden’s re-election effort” — and her role is “only expected to grow in the new year.”

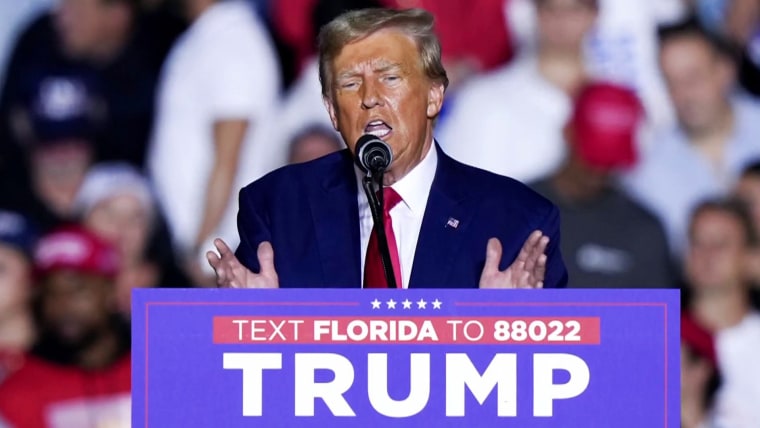

This isn’t exactly promising news for Biden’s already-troubling re-election prospects. While Clinton is popular with certain segments of the Democratic Party, she also has a track record of alienating progressives and swing voters in a contest against the very person Biden is likely to face in November — former President Donald Trump. Relying on Clinton as a high-profile surrogate is a risky proposition.

Clinton’s incremental theory of change and her hawkish record are more suited for an earlier era of the Democratic Party.

Clinton certainly has her assets. She’s a whip-smart policy wonk, she's popular among women, and she has a lot of pull as a fundraiser. She’s not only well-connected among party elites and megadonors, but her ability to draw on the star power of her husband, former President Bill Clinton, for high-dollar event appearances also makes it even easier for her to rake in money for Biden. Some establishment-friendly parts of the Democratic base believe that Clinton was robbed of a chance to win the White House by sexist news coverage and by former FBI Director James Comey, and they’re fond of seeing her back in the mix, showing up on shows like “The View” to share crisply articulated objections to Trump or Hamas. While former President Barack Obama has a habit of hanging back until late in a race to start whipping up attention for a candidate — much to the chagrin of many Democratic operatives — Clinton’s early presence signals party unity and solidarity.

But Clinton also carries a number of liabilities. At this stage, before Biden focuses on his general election pitch, the most obvious one is that Clinton embodies the Democratic establishment that angers and repels progressives needed to win the election. In the race for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2016, she was an avatar of the old guard as she faced off against Sen. Bernie Sanders' surprise left-wing insurgency against the Democratic establishment. This might seem like a strange distinction to make when Biden is also a longtime establishment Dem, but Biden’s reputation with progressives in 2023 is significantly different from what it was before 2020. Because of Biden’s first-term ambitions and policy record on issues like labor, climate policy, anti-poverty policy and his decision to stick to his guns on withdrawing from Afghanistan, he is perceived as malleable and open to input from the left. Clinton has no comparable arc, and so she is more susceptible to progressive and left-wing criticism. Her surrogacy could also signal to voters, correctly or incorrectly, that Biden is leaning toward his old ways more than his new ones.

Clinton’s incremental theory of change and her hawkish record are more suited for an earlier era of the Democratic Party, and every time she weighs in on contemporary issues, there’s a possibility that she’ll generate friction with younger and more left-leaning Democrats — and push them away from Biden. Consider, for example, how protesters have carried out sit-ins objecting to her stance on Israel policy and heckled her during public remarks over the issue. Clinton isn’t staking out positions that diverge significantly from the Biden administration’s, but she does have a somewhat more bellicose worldview and symbolizes the hawkish side of the Democratic Party. That makes her a particularly attractive target for left-leaning critics and protesters when she’s making comments in public. In other words, Clinton provides progressive activists with more opportunities to lash out at Biden and the Democratic establishment — which in turn could dampen progressives’ enthusiasm ahead of November.

Clinton’s salience when Biden pivots to general election efforts is also a concern. Clinton faced some unique obstacles as a candidate in 2016, but she was also a weak candidate. At a moment of populist upheaval, she insisted on technocratic change. She lacked a coherent policy vision and oratorical prowess, and she made critical strategic campaigning errors. She lost the election not only after having lost millions of Obama voters to Trump — many of them white working-class voters whom Biden partially won back — but also by failing to inspire many of them to vote at all. (She did win the popular vote by two percentage points, but she failed to secure victory in battleground states despite Trump’s clownishness candidacy.) In a tight race in which Biden is facing off against the same candidate she lost to, she’s far from an ideal campaign attack dog. For both fair and unfair reasons, she’s uniquely vulnerable to criticism from Trump and his allies.

Biden needs fresh, uncontroversial energy to help counter the perception that the political establishment could amble on with business as usual in his second term. The reality is that most influential surrogates are, by definition, going to represent that establishment. But the unique circumstances surrounding 2016 and 2024 make Clinton a poor surrogate to take the lead on behalf of Biden.