There are stories where a character does something so profoundly strange and contrary to their nature, the late Nobel Prize-winning novelist Toni Morrison taught, that readers won’t accept the actions as believable unless the character is Black. That’s true in literature, the writer argued, because it’s true in life: “We’ve always been considered to be irrational, emotional, lunatic people.”

And so it was in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina 20 years ago, when poor Black people became the face of the suffering and their alleged irrationality made the headlines and served as fodder for pundits disparaging the city and its people.

It’s inconceivable that stories of people aiming to shoot down rescue helicopters would have been swallowed if they weren’t stories of Black people doing such things.

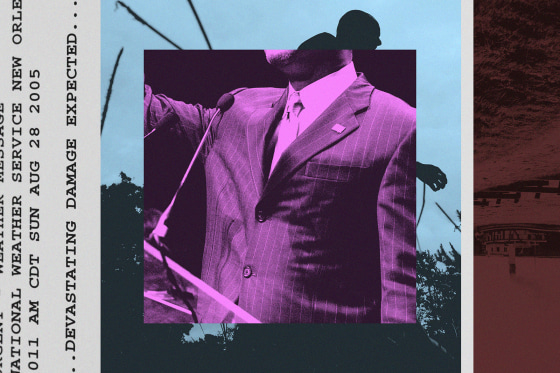

It’s inconceivable that stories of people aiming to shoot down rescue helicopters, raping babies and slaughtering one another inside the city’s makeshift shelters would have been swallowed and regurgitated as often as they were if they weren’t stories of Black people doing such things. Though then-Mayor Ray Nagin is Black, he was betraying a belief in what Morrison termed “Black irrationality” when he said the people waiting to be rescued out of New Orleans had become “almost animalistic.” And New Orleans Police Superintendent Eddie Compass, also Black, was doing the same when he said snipers were targeting rescue helicopters. The white governor, Kathleen Blanco, suggested that looters be shot, and white law enforcement officers turned away people trying to flee New Orleans on foot.

I told a room full of journalists at this month’s National Association of Black Journalists convention in Cleveland that one of Katrina’s big lessons is that no lie about Black people is too outrageous to be believed. So we journalists must refuse to be credulous.

Obviously, we’re never supposed to just accept what we’re told; we’re meant to embrace skepticism as a core value. But sometimes we become a little less skeptical when a source is a public official. And sometimes we feel compelled to quote a public official’s lies because they’re a public official. But when statements clash with what we know about human behavior, we shouldn’t feel obliged to just play along or believe we should be exempted from accountability when our reporting is helping to wrongly malign a group of people.

Consider the Republican presidential ticket’s slanderous claim that Haitians in Ohio were hunting their neighbors’ pets for food. Some people believed it because, again, they’ve been primed to believe the worst about Black people.

As Haitian Times publisher Garry Pierre-Pierre wrote for MSNBC, the community was later subjected to bomb threats. And since taking the White House again, President Donald Trump has demanded that Haitians here on temporary protected status get out.

Trump’s lying has prompted journalists to think more about how to balance a commitment to the truth with the desire to cover what public officials say.

Trump’s blatant and unapologetic lying has prompted journalists to think a lot more seriously about how to balance a commitment to the truth with the desire to comprehensively cover what public officials do and say.

But I’ve been wrestling with that dilemma for at least 20 years. I saw what happened when accurate quotes from official sources helped the world believe that the people in my city had gone feral.

Two weeks after the hurricane, Lt. Gen. Russel Honoré, the officer who had brought calm to a city on the brink of chaos (and who has written a Katrina anniversary column for MSNBC) walked into The Times-Picayune’s temporary office in Baton Rouge and met with the editorial board. Between explaining the vastness of Katrina’s destruction and promising to help jump-start the city so that we could work from there again, he provided an anecdote about a truck rolling over a capped plastic water bottle near a hospital loading dock. Nurses who were rolling a patient out for transport became so startled at the sound, he said, that they rushed their patient back inside, thinking they’d heard a gunshot. And what he described as “hysteria” followed.

For 2020’s “Floodlines,” a Hurricane Katrina podcast hosted by The Atlantic’s Vann Newkirk II, Honoré said he chided the police chief for claiming there were snipers. He said he asked Compass, “Did they hit you?” He answered no. Then, “Did they hit the helicopter?” The chief said no. “Well, they probably weren’t f-----g snipers, were they?”

Compass confirmed on the podcast that Honoré had been upset about what he’d said and acknowledged that “I shouldn’t have used that word.” He said, “I’m sorry. I mean, I can’t take it back.”

But the problem wasn’t “that word” but the suggestion that stranded people were trying to shoot helicopters out of the sky. Why wasn’t that dismissed as preposterous on its face? It seemed not to occur to folks making such claims that people afraid of being overlooked and left to die might make as much noise as possible. As one man who was rescued by helicopter later told The Times-Picayune, “Shouting toward a helicopter is really not going to do much.”

Why wasn’t that dismissed as preposterous on its face?

Honoré told Newkirk that people had “watched too much television. And they think if they shoot in the air, the helicopter will hear them and come get them.” Then, he said, “We have yet to have one helicopter with a bullet hole in it.”

No, it wasn’t safe for people left suffering in unquenchable heat to be firing guns when helicopters were up. But it wasn’t depraved, either.

My first big assignment after Hurricane Katrina involved collecting survivors’ stories. One man described being plucked from the water and left barefoot on Interstate 10. He said a man asked him his shoe size, walked off and returned with new Air Jordans. A woman who’d stayed with her elderly mother at a nursing home said they’d been fed Popeyes and snacks and provided Gatorade, adult diapers and wipes by teens making stops in the neighborhood on a mail carrier’s truck.

I don’t profess to know what fraction of crime was driven by charity and what fraction arose out of anger and greed. But I know the conditions that week were more horrible than the people were. It’s to our profession’s shame that journalists didn’t always convey that. And that some believed stories about Black people in New Orleans that they’d never have believed about anybody else.