Each new development in Donald Trump’s federal criminal case in Florida makes it increasingly clear that the impartiality of presiding Judge Aileen Cannon might, as federal law puts it, “reasonably be questioned.” That’s important because the same statute — 28 U.S. Code Section 455 — provides that when a judge’s impartiality might reasonably be questioned, the judge “shall disqualify” herself from the case. It’s time for a fair, impartial and independent judge to assume responsibility for this case.

There is a virtual mountain of evidence in the Florida case in favor of Cannon’s removal. Even before the case commenced, when Trump complained in a court about the FBI seizing his stuff, Cannon ordered the Justice Department to stop investigating the classified documents that were retrieved from Trump, despite them being seized under a lawfully issued search warrant. She then appointed a special master to review the evidence the FBI had taken, bringing the investigation to a grinding halt.

I can’t overstate how unusual it is for a federal court judge to decline to set a trial date.

The 11th Circuit Court of Appeals reversed Cannon, finding that she had abused her judicial discretion and emphasizing that no judge has the authority to interfere in an ongoing DOJ investigation. In layman’s terms, Cannon did something that the law did not authorize, and she did it to Donald Trump’s extreme advantage. And that was even before the actual prosecution came into existence.

In June 2023, Trump was indicted in the Florida case. The New York Times reports that after the case was assigned to Cannon, “two more experienced colleagues on the federal bench in Florida urged her to pass it up and hand it off to another jurist.” Cannon refused, yet ever since we’ve seen a steady stream of conduct that supports the conclusion that she is either incompetent, in the tank for Trump, or both.

Start with Cannon’s refusal to set a trial date, even though the case has already been kicking around in court for a year. I can’t overstate how unusual it is for a federal court judge to decline to set a trial date, particularly after the defendant’s lawyers informed that judge that they could be prepared to go to trial on Aug. 12, 2024.

Judges set trial dates. It’s kind of what they do. It’s important to have a date-certain for trial because all intermediate deadlines in a criminal case are driven by that timeline. Once a trial date is set, judges will set deadlines for motions to be filed, litigated and resolved in advance of and dependent upon the trial date. Simply stated: No trial date, no intermediate deadlines need to be set.

But because there’s no trial date, Cannon has deigned to set seemingly endless evidentiary hearings on motion after motion, mostly from Trump’s team. Adding insult to legal injury, Cannon is holding lengthy hearings on motions that most outside observers consider frivolous.

A quick word about legal motions in criminal cases: When a defendant files a motion, the defendant must articulate sufficient facts and applicable precedent that, if proven, would actually entitle the defendant to some form of relief or remedy. When a defendant fails to meet this “burden of production,” judges will almost always resolve the motion with a single word: “denied.” But Cannon seems to ignore the burden of production requirement, instead setting time-consuming evidentiary hearings.

For example, earlier this month Trump filed a “spoliation of evidence” challenge, arguing that because the FBI didn’t document the exact location of each item inside each box that was seized from Mar-a-Lago, that somehow equates to the FBI intentionally destroying exculpatory evidence. Having reviewed seized evidence in hundreds of criminal cases over my 30 years as a federal prosecutor, this assertion is absurd.

It’s hard to see how Cannon’s impartiality isn’t open to being reasonably questioned.

When the FBI executes a search warrant, evidence technicians thoroughly document the evidence as it appeared on the scene before it was seized. If the evidence is contained in a box, they’ll open the box and photograph the contents as it appeared when they first viewed it. Then, they’ll bring the box to an FBI facility, remove each item from the box, and meticulously document each item with photographs, written descriptions, etc.

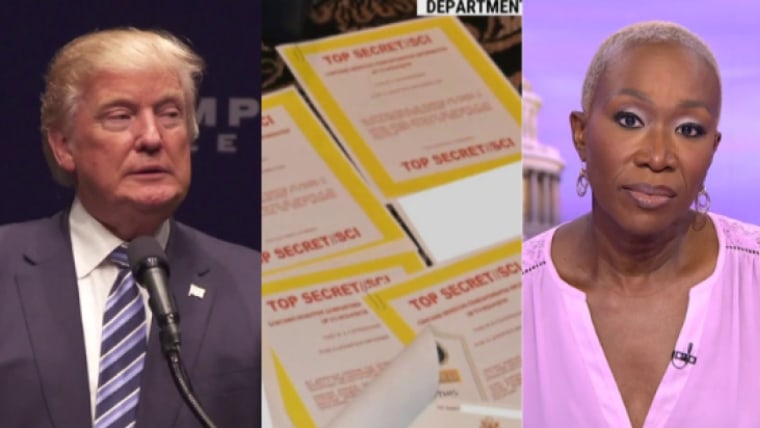

Recently published photographs of the evidence seized at Mar-a-Lago show that the boxes contained a mangled mess of classified documents, golf shirts, newspaper clippings, U.S. military plans, etc. Trump’s claim that it was important to know if a particular classified document was nestled against a balled-up golf shirt or a magazine cover depicting Trump — in other words, that the exact placement in the box is somehow of factual and legal significance — is entirely frivolous. Yet Cannon has refused to dismiss the motion, or even to commit one way or another on holding a hearing.

Then there is Cannon’s risible handling of jury instructions. Trump has argued that the Presidential Records Act (PRA) authorized him to take top-secret classified documents and national defense information to his Florida resort when he left the presidency. But in substance, the PRA’s text supports the opposite proposition: Classified documents remain the property of the federal government after a president leaves office. In some limited circumstances, presidential diaries, personal notes and other similar documents can be designated as personal rather than presidential records, such that a president can take his diary with him when he leaves the presidency. Classified documents, however, must be delivered to the National Archives for preservation.

Against that backdrop, in March Cannon asked both sides to propose jury instructions that accounted for two “competing scenarios.” Problem is, both scenarios inaccurately applied the PRA to the case, ignoring the law’s purpose and intent. Nevertheless, Cannon instructed the parties that they must assume her instructions were correct formulations of the law.

To be clear, judges will occasionally propose a jury instruction and ask the parties how they view that instruction, whether they believe it is an accurate formulation of the law, and whether they would propose any alternative instructions to the one offered by the judge. But I’ve never seen a judge offer what is obviously an incorrect assertion of law and direct the attorneys to assume it’s correct.

Earlier this month, retired federal judge Shira Scheindlin, who served for 27 years as a judge in the Southern District of New York, expressed her concerns that Cannon was showing “favoritism” toward Trump and antagonism toward the prosecutors in the case. Scheindlin also said that, in her experience and estimation, it’s apparent that Cannon is either unable or unwilling to discern what motions can be resolved on the papers with a simple “denied,” and which motions actually require an evidentiary hearing.

“I think she is inexperienced, and I think it makes her insecure in her rulings,” Scheindlin concluded, “But the motivation may be mixed in with intentionally delaying enough to make sure this doesn’t go before the election.” When such concerns and criticisms of a judge’s suitability to preside over a given case are voiced by current and former federal judges, it’s hard to see how Cannon’s impartiality isn’t open to being reasonably questioned. It’s long past time for her to hand off this crucial case.