On Dec. 9, 1895, the Senate voted to confirm Rufus Peckham, a judge on the New York Court of Appeals, to a seat on the Supreme Court. Peckham’s nomination wasn’t especially dramatic; the Senate confirmed him by voice vote just six days after President Grover Cleveland submitted his nomination. But it was the last time, to date, that a Republican-controlled Senate confirmed a justice nominated by a Democratic president. To be fair, until 2016, that statistic was almost entirely a fluke; there were only 12 years from 1895 to 2017 with a Democratic president and a Republican Senate, and no Supreme Court vacancies to fill. But we know what happened when a vacancy did arise in 2016: Republicans stonewalled for more than 10 months, refusing to even hold hearings for Merrick Garland, President Barack Obama’s nominee to succeed Justice Antonin Scalia.

We’re in for an extended period during which Supreme Court seats won’t be filled when different parties control the White House and the Senate.

This time around, of course, the Democrats have the votes. Even with the Senate Judiciary Committee divided evenly on Monday, it’s not a matter of if Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson will be confirmed as the 116th justice in the court’s history, but when. And yet, the vote is going to be far closer than it should be — presumably one of the closest in the court’s history. This, coupled with the behavior of Republicans at Jackson’s confirmation hearing, and the self-serving statements many have since put out in defense of their votes against her confirmation, drive home that what happened in 2016 was not a fluke. We’re in for an extended period during which Supreme Court seats won’t be filled when different parties control the White House and the Senate. And whichever side of the aisle you sit on, that’s a bad thing for the court as an institution — and for the country writ large.

Consider Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina. On June 14, 2021, Graham was one of three Republicans joining all 50 Democrats in voting to confirm Jackson to the D.C. Circuit — by tradition, the second most-powerful court in the country, and a common stepping-stone to the Supreme Court. (Three of the court’s current justices — Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh — followed the same path). Graham has also long promoted his record of having voted for every Supreme Court nominee who has gotten a vote in the Senate (sorry, Garland), and has repeatedly insisted that, when it comes to judicial confirmations, “elections have consequences.”

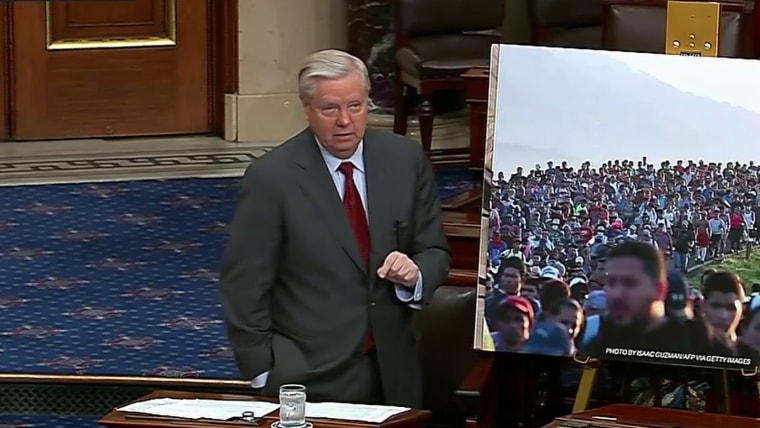

This time around, though, Graham is a “no.” Speaking on the Senate floor, Graham actually went even further than that, claiming Jackson wouldn’t have even gotten a hearing had Republicans controlled the Senate. He claims that his opposition is based upon Jackson’s “record of judicial activism, flawed sentencing methodology regarding child pornography cases, and a belief that Judge Jackson will not be deterred by the plain meaning of the law when it comes to liberal causes.”

Referring to her as an “evasive witness” (apparently on the assumption that those reading his statement didn’t watch the hearing) Graham’s Twitter statement never even tried to reconcile his vote to confirm Jackson just 40 weeks earlier. And given the extent to which Democrats and Republicans alike have repudiated the specious charge about Jackson’s record in child pornography cases, the statement seems more an attempt to rationalize a political decision already made than a serious effort to explain a principled change-of-heart.

Graham is not alone. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky justified his “no” vote largely by referring to Jackson’s refusal to disavow court-packing, never mind that Jackson’s answer was virtually the same as the one given by then-Judge Amy Coney Barrett at her 2020 confirmation hearing, or that, as a justice, Jackson would have literally no say over whether Congress added seats to the Supreme Court. Across the board, the case “against” Jackson is mostly just smoke and mirrors — designed to lend the veneer of substance to a vote that is, in every possible sense, just about politics.

It’s not exactly news that the Supreme Court confirmation process is political. Republicans point to Senate Democrats blocking the nomination of ultra-conservative D.C. Circuit Judge Robert Bork in 1987, and voting either unanimously or almost unanimously against the nominations of then-Judges Barrett, Kavanaugh and Gorsuch, as evidence that turnabout is fair play. But that charge depends upon ignoring critical differences between those cases and this one.

In Bork’s case, for instance, President Ronald Reagan had nominated a judge even more conservative than the most conservative justices on the court today to what had been the swing seat on the court — replacing Justice Lewis Powell. The vote on Bork came 13 months after the Senate unanimously confirmed Scalia. And Reagan’s next choice after Bork, Judge Anthony Kennedy of the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, was also confirmed unanimously less than four months after Bork’s defeat. In other words, the same Democratic senators who torpedoed Bork’s nomination supported both Scalia and Kennedy — both of whom moved the court sharply to the right.

The same Democratic senators who torpedoed Bork’s nomination supported both Scalia and Kennedy — both of whom moved the court sharply to the right.

As for the Trump appointees, there were far more than ideological objections to each of the three. Much of the objection to Gorsuch’s nomination was fallout from the Garland affair. The ultimate fight over Kavanaugh’s nomination had far more to do with the sexual assault allegations made against him than anything about his ideological preferences. And Barrett’s rushed nomination process, begun before Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had even been buried, seemed deeply hypocritical given the lengths to which Republicans had gone in 2016 to oppose election-year Supreme Court confirmations. People may disagree about the strength of those procedural objections, but they went far beyond simple disagreements over the nominees’ perceived judicial philosophy.

Jackson’s nomination, in contrast, comes with none of that baggage. Everyone agrees that, if confirmed, she would have at most a modest impact on the court’s center of gravity. Procedurally, the timing of the nomination has been by the book. And Jackson’s record, the efforts of Republicans to scaremonger notwithstanding, is that of a faithful, principled, center-left judge — who will be not nearly as far to the left as any of the court’s six conservative justices are to the right. In that respect, her confirmation vote ought to look a lot more like Roberts’ 2005 vote (78-22) than like Barrett’s vote in 2020 (52-48).

Instead, the central reason why almost every Republican opposes her is because she was nominated by a Democratic president, and nothing more. There’s nothing unconstitutional or illegitimate about such a vote; the Constitution leaves the confirmation process to the Senate for a reason. But it’s yet another significant escalation in the ongoing race to the bottom.

If qualified nonextreme nominees can be opposed this way, that means that the era of cross-party confirmations (in which Democratic Senates routinely confirmed Republican nominees) is effectively over. And just as we saw in 2016, that means that seats will be left open — on lower courts and the Supreme Court — whenever vacancies arise during such a period.

Not only will that make it harder for split courts to function (the Supreme Court can’t act when it divides 4-4, and would lack a quorum if it had fewer than six seats filled), but it will also only reinforce the growing perception that the courts are little more than another lever through which partisan political power can, and is, exercised. In the short term, that will obviously benefit whoever has that power. In the long run, though, it will leave all of us — and the Supreme Court as an independent institution — worse off.