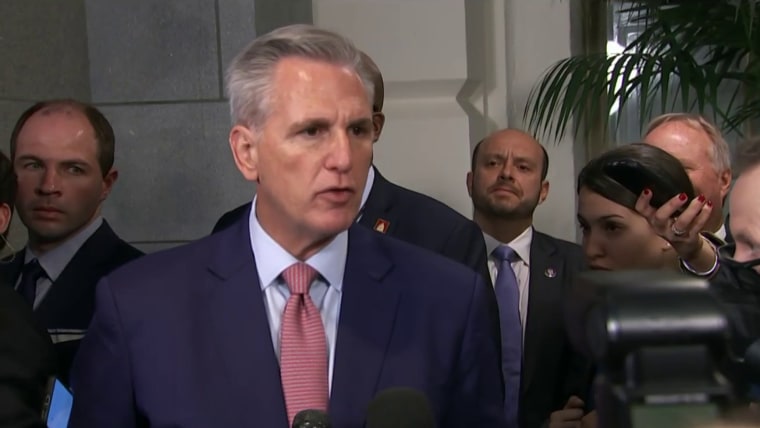

The first day of the new Congress opened and closed on Tuesday — and there is no speaker of the House. California Republican Kevin McCarthy failed on three consecutive ballots to get the majority needed to take up the speaker’s gavel, leaving the chamber in limbo.

It’s easy (and fun) to make fun of McCarthy, who became the first party leader to lose multiple rounds of voting for speaker in nearly a century. But it’s not clear that any other Republican can do much better once taking up the speaker’s suite in the Capitol. In the last three decades, a fundamental disconnect has arisen between the requirements of the speakership and the political dynamics within the House Republican Conference. The skills it takes to succeed at the former are constantly at odds with the latter. And as McCarthy has seen up close, there is no hesitation among House Republicans to mutiny against their own leadership.

A fundamental disconnect has arisen between the requirements of the speakership and the political dynamics within the House Republican Conference.

The tension between leading the House and leading the GOP caucus has been developing since Rep. Newt Gingrich of Georgia led the Republican Revolution during the 1994 midterms. That year, the GOP reclaimed a House majority for the first time since 1955. Since then, Gingrich and three other Republicans have served as speaker. All but one were forced from the position thanks to rebellions in their ranks.

Gingrich himself resigned shortly after the 1998 midterms — his strategy of impeaching President Bill Clinton blew up in Republicans’ faces. In 2015, John Boehner of Ohio — who had helped Gingrich draft the Contract with America that laid out the GOP's agenda — was driven out when his willingness to prioritize keeping the government running clashed too many times with the ascendant tea party’s hard-line demands. His successor, Paul Ryan of Wisconsin, chose to resign from Congress rather than run in the 2018 midterms after two years of working with President Donald Trump.

The one exception, Dennis Hastert of Illinois, lasted eight years — he was the longest-serving Republican speaker in history. Hastert developed the informal rule bearing his name whereby only bills with the support of a majority of Republicans would come to the floor. It worked, for a time, to keep the caucus unified even as President George W. Bush’s popularity plunged. He resigned after the 2007 midterms instead of serving as minority leader. (Hastert was also later convicted of structuring bank withdrawals to hide hush money paid to cover up his past sexual abuse.)

So why is it that Gingrich, Boehner, Ryan and now McCarthy have struggled to be able to control the caucus that they — in theory — controlled? The problem boils down to three parts: principle, power and politics. Modern conservatives have long argued that the decentralization of power is necessary for a democracy to function. (Trump’s authoritarian streak and the unitary executive theory that enabled it being glaring exceptions to the orthodoxy.)

The role of speaker, by contrast, has evolved in a way that affords near-total control of the House agenda, wresting control away from committee chairs who for decades ruled their jurisdictions as their own personal fiefdoms. Boehner in particular drew animus from rank-and-file members for his willingness to push bills that he negotiated with Democrats in the White House and the Senate. One of the complaints that Rep. Chip Roy, R-Texas, listed Tuesday when he nominated Rep. Jim Jordan, R-Ohio, on the third ballot was that it had been years since floor amendments were allowed on major bills that had been hammered out among congressional leadership. (Jordan, it's worth noting, had been one of the driving forces behind Boehner's exit.)

But withdrawing power from the committees has made committee assignments a less effective lever for GOP speakers to keep their members in line. The congressional earmarks that members used to be able to take back to their districts to show their victories were also taken off the table under Boehner — with the tea party’s support — as part of Republicans’ war on big government spending, further cutting off a potential method of corralling wayward members.

No matter who comes out on top, though, that person will be ruling over a caucus of cannibals.

The other major factor that has led to the chaos we saw Tuesday is pure, uncut political self-interest. The GOP’s rightward swing that Gingrich so effectively harnessed in 1994 has only kept swinging since then. Thanks to gerrymandered districts, the only thing most GOP representatives have to fear every two years is primary challenges from their right — and there’s never a shortage of candidates willing to accuse an incumbent of insufficient conservative purity. Members who win seats are all too often those who promise combat over compromise and prioritize “owning the libs” over actually governing.

Therein lies the problem for GOP speakers: The speakership is at its core a nonpartisan role. It is a position of leadership over the House as a whole, charged with keeping the wheels turning in the chamber most directly accountable to the people. That responsibility requires cutting deals in a divided government, especially in as narrowly split a Congress as the one McCarthy wishes to preside over.

So far the deals McCarthy has been cutting have been with his own caucus’s far-right holdouts, including making it easier for the speaker’s chair to be vacated, further weakening his hand. And yet 20 of his own members still continued to vote against him Tuesday, with at least five vowing to never support him under any circumstances. All other business in the House will remain ground to a halt for however long it takes to break the impasse. Which is fine for the holdouts, many of whom have no legislative agenda to pass or particular desire to leave the spotlight that their “principled stance” against McCarthy affords them. They know there will be no punishment that could possibly outweigh the benefits that even a failed assault on McCarthy as an avatar of the status quo can provide them.

When Gingrich stepped down from the speakership in November 1998, he famously told his fellow Republicans: “I’m willing to lead, but I’m not willing to preside over people who are cannibals.” It’s not clear how this all ends. Democrats won’t give McCarthy the wiggle room to get over the top, while his opponents will dig in for even more votes Wednesday. No matter who comes out on top, though, that person will be taking on a cursed job, doomed to rule over a caucus of cannibals, ones who have no qualms about spending the next two years making the business of government all but impossible to carry out.