UPDATE (Jan. 7, 2023 12:30 a.m. E.T.): Republican Kevin McCarthy finally became House speaker early Saturday morning, on a historic 15th ballot.

According to many of its critics, the Republican Party has become an authoritarian party. The GOP, they argue, has developed a distaste for the trappings of democracy, cultural heterogeneity and the unenumerated norms that make republican self-rule work. It is difficult to square this ubiquitous indictment with the successes some of the most populist House Republicans have enjoyed in their unrelenting campaign to deny Rep. Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., the speaker’s gavel. They are compelling an aspirant to one of the Constitution’s highest stations to disaggregate that office’s authority — and reflecting a broader, if halting, trend toward a more “democratized” party.

A stronger institutional leadership — indeed, a stronger Republican Party — might have intimidated the GOP’s would-be mutineers from costing McCarthy the speakership.

It was evident well over a year ago that McCarthy would make for an uninspiring speaker of the House, if only because his record as minority leader was so thoroughly blemished. McCarthy invested untold sums of political capital in the idea that the MAGA wing of the GOP would springboard him into leadership. Toward that end, he committed to giving Reps. Paul Gosar, R-Ariz., and Marjorie Taylor Greene, R-Ga., the committee posts they lost because of their violations of decorum. By contrast, he heaped scorn on such figures as Rep. Liz Cheney, R-Wyo., reliable conservatives who highlighted his own duplicity by refusing to compartmentalize the revulsion they felt after Jan. 6.

McCarthy made himself out to be a steward of the populist right’s priorities, but he's hardly an effective one. He couldn’t marshal his forces in support of partisan Republican priorities, nor could he corral Republicans in opposition to Democratic objectives. A revolt was inevitable. And yet, a stronger institutional leadership — indeed, a stronger Republican Party — might have intimidated the GOP’s would-be mutineers from costing McCarthy the speakership. Even if their efforts are ultimately unsuccessful, the concessions they have received from McCarthy reveal much about the direction in which the party is headed. That direction could be described in many ways, but “authoritarian” isn’t one of them.

Before voting began, McCarthy hoped he could mollify his critics within the Republican conference by giving in to some, but not all, of their demands. Among them, he agreed to reduce the threshold to trigger a “motion to vacate” the speakership from half of the majority party to just five of its members. He approved new rules that would allow members to introduce and debate germane legislative amendments. He acceded to demands that would allow public input in House ethics investigations; scrapped Democratic conventions like “pay-as-you-go” and the “Gephardt rule,” which ceded budgetary authority to the Senate; and restored an old rule requiring supermajority support for tax hikes.

Six subsequent inconclusive speakership votes demonstrated that wasn’t good enough. So McCarthy and his allies went back to the well. He finally abandoned his opposition to a core demand of his critics, allowing just one member to introduce a “motion to vacate.” He offered a vote on legislative term limits. He would countenance stand-alone votes on each of the annual appropriations bills and allow an “open rule,” which gives all members — including Democrats — the opportunity to debate and form bipartisan coalitions around their priorities. McCarthy even conceded that his political action committee wouldn’t engage in primary races in dark red districts vacated by incumbents, leaving the work of party-building to organizations outside the party.

There’s a lot to be said in support of what the GOP’s insurgents sought and secured from McCarthy. Regular order and checks on sprawling omnibus bills and Build Back Better-style monstrosities are agenda items most Republicans can get behind. At least, in theory. But many of the conventions McCarthy’s critics are targeting exist for a reason.

Many of the conventions McCarthy’s critics are targeting exist for a reason.

The Republicans demanding that “earmarks” get their own votes, thereby ensuring there would be fewer “earmarks,” deride them as giveaways for no higher purpose than preserving members’ incumbency. But specific appropriations sought by representatives closest to their districts serve real purposes, and they’re rounding errors in budgetary terms. Depending on the details, term limits would ensure that no lawmaker was around long enough to fully understand how to navigate Congress, leaving that to the former lawmakers and glad-handers who populate lobbying outfits. Big, sprawling compromise bills are big and sprawling to attract as many votes as possible, whereas single-issue legislation often fails in the absence of either a crisis or a prohibitively large majority. And the “open rule” provision would expose vulnerable Republicans to politically damaging show votes.

Ultimately, these conventions exist to protect the majority party and grease the skids for legislation. Getting rid of these conventions would be, in the definitional sense, a democratic enterprise. It would represent an effort to radically decentralize power — the antithesis of authoritarianism — even to the point of inviting anarchic disorder and paralysis. And it is an effort being spearheaded by some of former President Donald Trump’s most vocal supporters in the House.

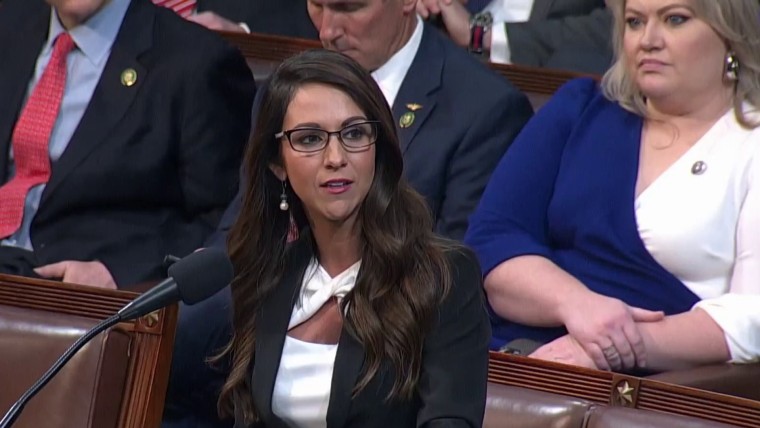

That last fact — and the former president’s minimal relevance in this debate — has confused some observers. How is it that Trump allies such as Reps. Matt Gaetz of Florida and Lauren Boebert of Colorado are openly scornful of Trump’s support for McCarthy? Why are we witness to an effort by a power-mad party to strip its leaders of power? That confusion arises from a failure to recognize a trend within the GOP that predates Trump: to disaggregate and democratize conventions that were once the exclusive provinces of party functionaries.

Even before Trump, the Republican Party democratized insofar as it allowed the organs of institutional authority to wither. It has become conventional wisdom that Republican lawmakers refrained from criticizing Trump or curtailing his executive authority despite plenty of evidence to the contrary. Over the last decade, the institutional GOP all but ceded its prerogative to intervene in the primary process and maximize the chances for electoral success, giving that up to the Club for Growth, grassroots PACs and conservative entertainers.

There is tension within the party over this trend, and it hasn’t progressed along a straight line. But the negotiations over McCarthy’s position in the party throw into stark relief the notion that the divide within the GOP isn’t between small “r” republicans and authoritarians but between republicanism and democracy in the Athenian sense of the word, with all its attendant dysfunction and syndicalism. Whatever the outcome of the battle for the speakership, at least it has helped us define our terms.