It has been surprisingly tricky to pin down the politics of Sen. Laphonza Butler, D-Calif., who was sworn in Tuesday to fill the late Dianne Feinstein’s seat. Her résumé is similar to those of many other Democratic political activists who have risen through the ranks. But Butler, a longtime ally of Vice President Kamala Harris, also has a résumé with enough apparent contradictions to raise a few eyebrows.

In theory, the scope of her experience and the variety of groups for which she has advocated are good things. By the nature of their jobs, senators are charged with representing a broad range of interests within a state. In Butler’s case, people can look at that variety and project onto her whatever they want to see as the future of the Democratic Party.

In theory, the scope of her experience and the variety of groups for which she has advocated are good things.

When examining the details of Butler’s career, the results of the Rorschach test only get more scrambled, depending on your frame of reference. When Gov. Gavin Newsom appointed her, Butler was serving as the president of EMILY’s List, a group that raises money for pro-abortion-rights political candidates around the country. Abortion tops Democrats’ agenda, and their stance is backed up in poll after poll and the results of last year’s midterms. Butler specifically named the fight for abortion access as one of her top priorities in an interview with the San Francisco Chronicle soon after she took her seat.

But recent reporting from The Intercept and HuffPost about her tenure at EMILY’s List has spotlighted her role in recent layoffs and a decision to invest millions to support Harris’ 2024 re-election bid.

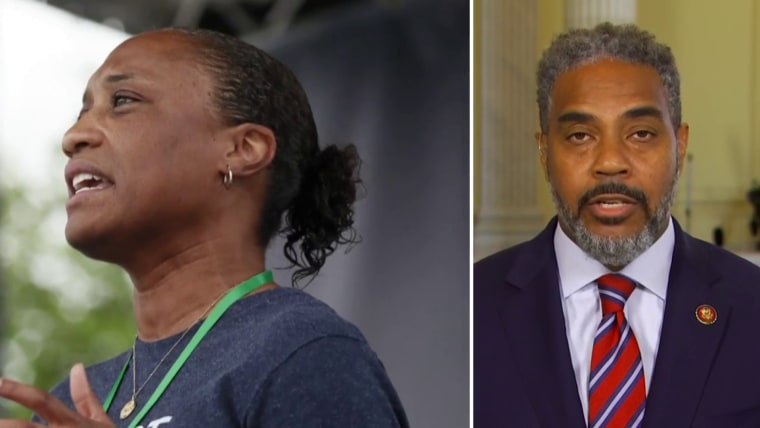

From one angle, you see the first — and only — Black female senator since Harris became vice president. But it’s not like she was the only person who fit the bill. The Congressional Black Caucus had urged Newsom to appoint Rep. Barbara Lee, D-Calif., to Feinstein’s seat, and most likely many members still wish he had listened. Lee declared back in February that she’s running for the seat, and Newsom had said he didn’t want to give any candidate an incumbent advantage in the already hotly contested primary. Butler, then, may not have been the best choice as an “interim” senator, since she hasn’t ruled out a run for a full six-year term herself.

Look at Butler from one direction and she’s a deeply pro-labor choice. She spent years as the president of Service Employees International Union Local 2015, California’s largest union, which represents about 400,000 long-term health care workers. During that same period, she helped lead the SEIU’s umbrella organization in California and had a stint as a vice president of the SEIU International. From her perch atop the state’s labor movement, Butler helped negotiate California’s $15-an-hour minimum wage in 2016, and unions have largely rallied around her appointment.

From another direction, Butler has disturbing links to some of Silicon Valley’s most heavily criticized corporate vultures. Prior to EMILY’s List, she was Airbnb’s director of public policy and campaigns in North America. Housing advocates have accused the vacation rental company of helping drive up housing costs by incentivizing owners to use properties for visitors rather than residents; the resulting backlash is still ongoing in New York and other metropolitan areas. Then there’s the matter of her time at SCRB Strategies, now doing business as Bearstar Strategies, where she “advised and represented Uber in its dealings with organized labor on employment issues,” according to a 2019 Bloomberg News report.

Uber and other app-based companies that built the gig economy were lobbying for exemptions from a draft law that would allow them to claim employees as mere contractors — which meant the companies wouldn’t be responsible for employee benefits or labor protections. The companies were ultimately successful (the Biden administration is now weighing whether federal regulations could close that loophole). Butler defended her work advising Uber in her San Francisco Chronicle interview but seemed intentionally vague about some of the details:

“I’ve been very clear that they should have the protections of employment,” Butler said. “I’ve spent my entire career, nearly 20 years, in the labor movement, working to make sure that workers who wanted a union have the opportunity to have a fair shot to build one. My work on AB5 was exactly that.”

Butler did not say specifically what her work on the measure entailed.

“My role was one that was consistent with my resume. There was no inconsistency in my work or my engagement,” Butler said Tuesday.

Meanwhile, Butler is also the first openly LGBTQ Black woman to serve in the Senate. The Human Rights Campaign lauded her appointment as “a landmark moment in the fight for social, racial and economic justice.” But there’s still a cynical undertone to Newsom’s choosing her, given his recent vetoes of both pro-labor and pro-LGBTQ legislation in his state. Butler definitely fits within the mold of the governor as someone who balances competing interests within the Democratic Party — but it’s unclear whether he intended her appointment as an olive branch or a fig leaf.

Until her votes show us which side she lands on, she exists in a liminal space

Here’s the view from where I’m sitting: Butler’s résumé straddles a division that’s shifting with increasing speed along the fault lines of what it means to be a stalwart Democrat. She lines up with most of the party on most issues. She’ll be a solid vote for President Joe Biden’s judicial nominees and expanded voting rights and against abortion restrictions and harmful spending cuts. And it’s only recently that Democrats have felt mounting pressure to support workers over corporate interests as the luster fades from the neoliberalism that once dominated the party’s thinking.

Butler could easily spend her next 14 months in the Senate aligning herself with the likes of Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., and John Fetterman, D-Pa., to strengthen labor rights and protections. Or she may wind up pushing back on proposals to rein in the tech companies she supported as a lobbyist. But until her votes show us which side she lands on, she exists in a liminal space, fitting whichever shape her supporters and detractors choose to perceive.