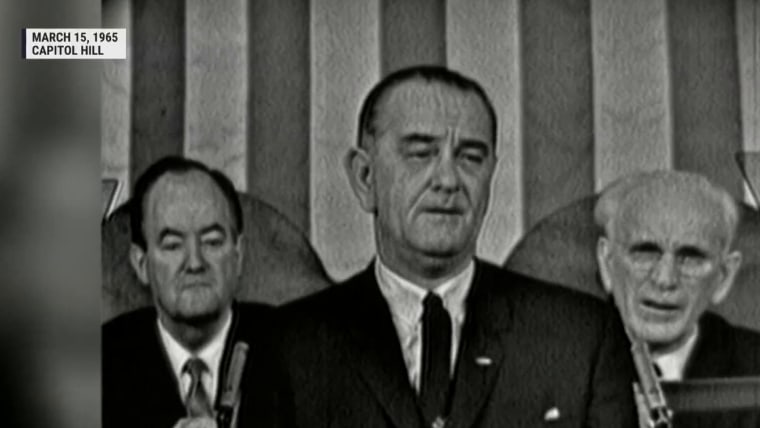

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 — one of the most transformative laws in American history. Signed into law after the Selma-to-Montgomery marches, the Voting Rights Act gave teeth to the 15th Amendment’s promise that no American could be denied the right to vote because of race. The results were undeniable. In places where Black voter registration had once been in the single digits, registrations surged. Black citizens who had long been shut out of the political process gained a voice on school boards, in state legislatures and in Congress. The Voting Rights Act was proof that when the federal government enforces equality, democracy becomes stronger.

The Voting Rights Act was proof that when the federal government enforces equality, democracy becomes stronger.

But anniversaries aren’t just moments of celebration; they’re moments of reckoning. As we are recognizing the 60th anniversary of this landmark legislation, Louisiana is at the center of a case — Louisiana v. Callais — that could completely erase the legacy of this act.

The dispute in this case is whether Louisiana can be required to draw two congressional districts where Black voters have a fair chance to elect candidates of their choice. Black people make up nearly a third of Louisiana’s population but historically have had influence in only one of six congressional districts. Federal courts have found that the congressional lines have been drawn in a way that dilutes Black people’s voting power in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The remedy is clear: create a second district.

The 14th and 15th amendments transformed the Constitution into a document that protects equality and democracy for all. These amendments finally enshrined rights for Black and minority communities into the Constitution where there were no explicit civil rights protections before.

After initially defending a recently created map that added a second minority-majority congressional district, Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill has executed a troubling bait-and-switch. She has pivoted to argue that race-conscious redistricting is itself unconstitutional under the 14th and 15th amendments. This is not just a reversal — it is a direct challenge to the Voting Rights Act itself. If her view prevails, Louisiana v. Callais could become the case that dismantles one of the last remaining protections for minority voters in America. These amendments were set to make a more perfect union. But now these very amendments that were used to give Black Americans rights are being cited in an attempt to dilute, oppress and suppress Black people’s voting powers.

This is no abstract risk. Courts have already found that a map that dilutes Black voting strength is a violation of federal law. Creating a second minority district is not a racial preference; it is a constitutional remedy to an undeniable civil rights violation. But Murrill’s new stance threatens to erase one of the last remaining safeguards of minority political power.

After years of advocacy from Black Louisianans, the state government in 2024 finally adopted a map that reflects the population of our state. As the attorney general of Louisiana, Murrill’s focus should be defending the Louisiana Legislature’s right to draw a congressional map that reflects our state’s population. Her decision not to defend it is an about-face, a reversal of her duty to uphold the laws of the state of Louisiana. Louisianians would be right to wonder if she is working for the Louisiana people or working to advance her standing with Trump’s MAGA movement?

Do we still believe in the law’s promise of equal representation?

This is why the anniversary of the Voting Rights Act matters so deeply. It is not about looking back with nostalgia but looking forward with resolve. Do we still believe in the law’s promise of equal representation? Or will we let legal theories dressed up as “color blindness” strip away protections that generations marched, bled and died to secure? To be clear, what we have seen over the last eight months of this new presidential administration shows us that this nation is nowhere near color blindness.

The stakes could not be higher. The question is not only whether Black voters in Louisiana will receive fair representation. It is whether the United States will continue to honor the hard-won protections of the Voting Rights Act — or allow them to be erased under the guise of constitutional purity.

We must decide what side of history we want to be on: the side that drags us back toward 1964 or the side that carries us forward into 2025, where liberty and justice apply to all of us.

The Voting Rights Act is not just legislation; it’s a covenant with the American people. Sixty years later, the question remains: Will we keep it, or will we break it?