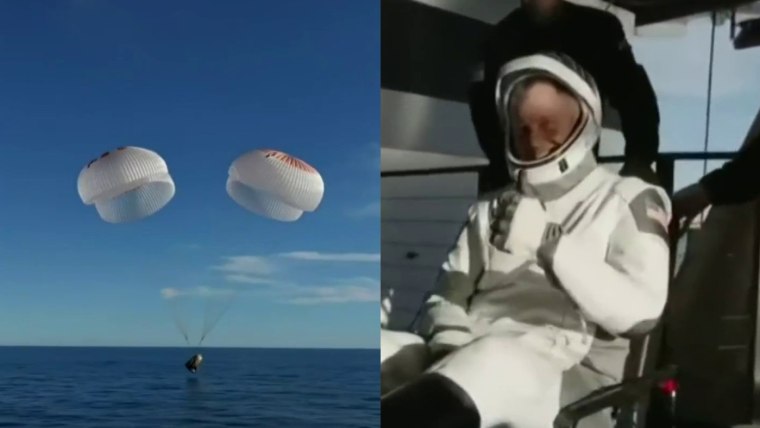

After nine months in space, NASA astronauts Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore finally came back down to Earth on Tuesday. Their return from the International Space Station marks a close to a trip that was supposed to last a week. Their odyssey highlighted how needlessly dependent the United States has become on private businesses to ferry brave American scientists and explorers to space and back.

The politics of space funding have shifted over the decades as enthusiasm grew for a more cost-effective solution to launches. But we’ve hit a point where the private ownership of America’s spaceflight capabilities has become a severe national security risk that threatens future projects.

Williams and Wilmore ventured to the space station in June aboard the first crew-tested flight of the Boeing Starliner capsule, but two issues made it unsafe to deliver them home. They returned in a SpaceX Dragon capsule, which has been used in most of NASA’s manned spaceflights in recent years. Boeing, a venerable aeronautics institution, and SpaceX, an upstart owned by Elon Musk, are now primarily how NASA delivers astronauts and cargo into low-Earth orbit.

NASA wasn’t so dependent on private companies when it conceived Project Mercury, the country’s first human spaceflight program. Given the pressures of the space race against the Soviet Union, there was no question that the new civilian program would own and operate its rockets and capsules. The work of building the Mercury spacecraft, like all military aircraft, was contracted out to corporations to carry out engineers’ designs. But NASA controlled the launches and crews.

That remained true for the Gemini and Apollo programs and the eventual development of the space shuttle, a reusable spacecraft that could glide to a landing rather than be recovered from the ocean. But the program was wildly more expensive than anticipated, and the prediction that businesses deploying satellites would prefer NASA over commercial rockets fell short.

It’s proved to be a lucrative market for SpaceX in particular, which over the last decade has snapped up NASA contracts worth $13 billion.

Challenger exploded seconds after launch in 1986, and Columbia exploded shortly after re-entering Earth’s atmosphere in 2003. Those two catastrophes drove the impression that the shuttle would never be truly safe. The shuttle program’s 30-year-run ended in 2011 when Atlantis landed at Florida’s Kennedy Space Center. There was no clear vision of what would come next, and by 2013, American astronauts were forced to ride Russian rockets into space at the cost of over $70 million per seat.

It makes sense that NASA would prefer a homegrown alternative, and as NBC News reported in 2011, the agency turned “to private industry with fixed prices, contracts and profit margins” as a solution, in an arrangement whereby the “space agency will be the customer, not the boss.”

Since then, companies including SpaceX, Boeing and Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin have vied for contracts to deploy people to the International Space Station as part of the Commercial Crew Program. In the meantime, there’s been plenty of opportunity to launch satellites and other cargo, as well. It’s proved to be a lucrative market for SpaceX in particular, which over the last decade has snapped up NASA contracts worth $13 billion.

NASA announced in August that a Crew Dragon spacecraft owned by Musk would be launched in February to retrieve Williams and Wilmore as part of a planned return mission for two other astronauts. But last month, Musk, who has thrown in his lot in with President Donald Trump, falsely claimed that he’d been blocked from sending a mission to retrieve Williams and Wilmore sooner for “political reasons.” Musk had lied that Trump had cleared the SpaceX recovery mission when it was President Joe Biden who did.

Musk, who is already profiting handsomely off NASA’s inability to launch its own flights, is positioned to steer even more business toward himself and away from his competitors. We should all be grateful that Williams and Wilmore are back home, but I’m frustrated that bringing them back further lined Musk’s pockets.

NASA should require that Musk divest from SpaceX and any profits it makes from government contracts for as long as he is serving in the government. This would most likely put a damper on further crewed missions until his competitors have a chance to safely catch up, but it would be better in the long run for the stability of America’s space program. But the thought of Trump’s putting constraints on SpaceX so long as he and Musk are friendly is as far-fetched as Musk’s dreams of colonizing Mars.