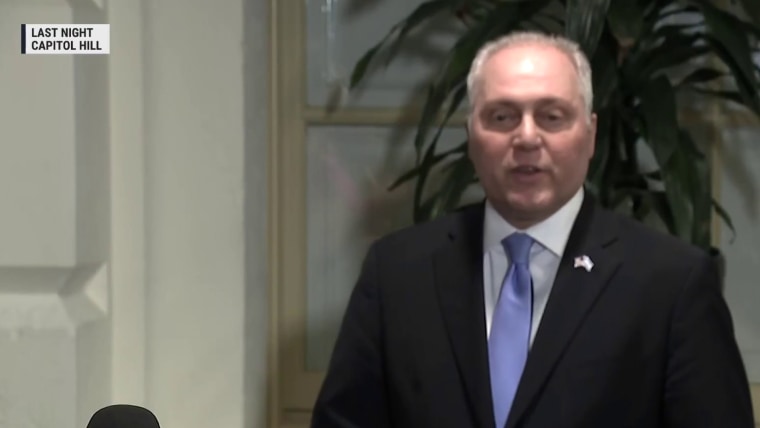

It’s been almost two weeks since a petty revolt among Republicans led to the first successful vote to overthrow a speaker of the House. Since the removal of Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., the House GOP has been running around in circles trying to find someone — anyone — who can garner enough support to take up the gavel. One nominee, Majority Leader Steve Scalise of Louisiana, has already bowed out for lack of consensus. There’s little evidence that the second candidate to win an internal vote, Judiciary Committee Chair Jim Jordan of Ohio, will fare much better.

As a result, the House floor has been quiet, save for the occasional pro forma session to give the illusion that the body still functions. Speaker Pro Tempore Patrick McHenry, R-N.C., hasn’t sought to test the limits of the limited powers he’s been given as a steward of the speakership. It feels fitting, in a terrible sense, that with the Republicans unable to name someone to speak for them, the people’s House has been silenced.

It feels fitting, in a terrible sense, that with the Republicans unable to name someone to speak for them, the people’s House has been silenced.

The role of speaker was much more literal when it originated in the British Parliament. When it was bestowed upon Sir Thomas Hungerford in 1377, the job was literally to be the spokesperson for Parliament in addressing the crown. “Until the seventeenth century, the Speaker was often an agent of the King, although they were often blamed if they delivered news from Parliament that the King did not like,” according to the U.K. Parliament’s website. “This made the role of Speaker quite perilous; seven Speakers were executed by beheading between 1394 and 1535.”

But as Parliament asserted its authority, the speakership became more independent. It also came to be seen as an essential part of legislative bodies, as evidenced once English colonies arose in North America. During the first parliamentary meeting at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619, one of the first acts of the assembled burgesses was to select a speaker. Other colonial legislatures followed suit, including North Carolina’s and Massachusetts’.

The apparent self-evidence of the necessity of a speaker means the Constitution is a little vague about one of the most important jobs in the country. Article I, Section 2 merely says, “The House of Representatives shall choose their speaker and other officers”; the job wasn’t mentioned at all in the Federalist Papers, and it didn’t appear in notes from James Madison and others attending the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Instead, as with so many things in America, the exact role of the speaker has been made up on the fly, at times gaining and losing functions as the years have passed.

It began more or less in line with the British version of the gig, simply managing the flow of debate among peers and staying aloof from the actual back-and-forth between members. As the party system took root, the speakership became the prize to be claimed by the head of the party in the majority at the beginning of each Congress. And as member of the Houses in their own standing, speakers also vote on legislation, although, according to the Congressional Research Service, voting at their discretion was allowed only after 1850.

It’s extremely fitting with the job’s historic origin that the modern speaker is also meant to be the chief spokesperson for the House. The speaker serves as the point person in negotiations with the White House and the Senate. The speaker holds weekly news conferences with the media to lay out the majority’s agenda. In this way, speakers serve as an embodiment of the will of the people in the more directly representative branch of Congress. There’s a reason the speaker was placed directly in the line of succession to the presidency after the vice president.

But the most consequential power the speaker holds is controlling the floor of the House: deciding who gets to speak, which motions get recognized and which bills come up for votes. Because that power hasn’t been transferred to McHenry in this interregnum, the legislative process has ground to a halt. Granted, the legislative process was often halted when McCarthy was speaker, as the far right defied his halfhearted attempts at order, but there’s a more desperate and uncertain feeling over the current paralysis.

While the floor remains silent, there’s a cacophony of voices elsewhere. With no speaker, it seems like factionalism is the order of the day, as every member of the Republican caucus is scrambling to be heard over their colleagues. Scalise was unable to win over McCarthy’s and Jordan’s supporters, which prompted him to withdraw his name from consideration. It’s unlikely that Jordan will be able to convince moderate Republicans that he can unite the party and not help cause a blowout for Republicans in competitive districts in next year’s elections. McCarthy’s dream of returning to power faces a similar math problem. And while talk of a bipartisan compromise candidate has a certain Aaron Sorkin-esque appeal, the practical reality of the job seems to preclude it — at least for now.

There’s no telling just now how long this impasse will last. As I’ve said before, the current makeup of the House GOP isn’t built to allow for coalitions, not even internally among its own members. There is no one voice who could rightly speak for the Republican caucus as it stands, because its members would rather cut out their own collective voice box than allow someone else to do it on their behalf.