Rudy Giuliani has spent the last few years facing a lengthy parade of investigations, allegations and lawsuits that has resulted in the suspension of his law license in New York and Washington, D.C., and made him the target of a criminal probe in Georgia for his efforts to overturn the 2020 election results. But even by those standards, the new wide-ranging civil allegations against the personal attorney for former President Donald Trump, unveiled in a lawsuit filed Monday, are deeply disturbing.

His post-mayoral pursuits of quick cash to support lavish spending have become the stuff of legend.

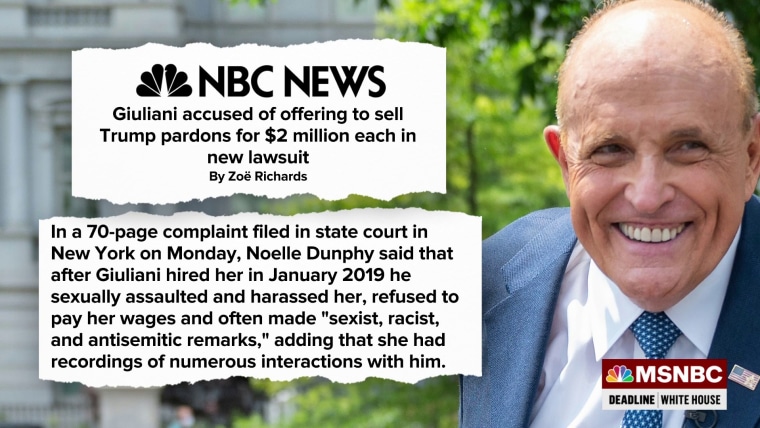

In brief, Noelle Dunphy alleges that over two years when the former New York mayor employed her in “secret,” Giuliani engaged in “unlawful abuses of power, wide-ranging sexual assault and harassment, wage theft, and other misconduct.” Amid other, more salacious details, one that stands out is a claim that Giuliani at one point asked Dunphy “if she knew anyone in need of a pardon, telling her that he was selling pardons for $2 million, which he and President Trump would split.” In a written statement to NBC News, a Giuliani spokesman said the former mayor “unequivically denies the allegations.” But between Trump’s abuse of the pardon power and Giuliani’s constant scramble for a buck, there’s a definite thread worth tugging on in the accusation.

For most of Trump’s tenure, the normal channels for requesting a pardon or a commutation had become massively clogged. Right-wing celebrities and prominent Trump supporters were some of the only beneficiaries of the president’s nearly unchecked pardon power. As of early December 2020, Trump had granted clemency just 45 times, a record low for that point in a presidency. Accordingly, in the waning days of his term, lobbyists and lawyers close to the administration were raking in thousands of dollars in consulting fees in exchange for a chance to get their clients’ names on the president’s desk.

Given that Giuliani and Dunphy’s alleged conversation took place in February 2019, according to the complaint, it seems Giuliani was ahead of the curve. At the same time, he was already deep in the scheme to extort Ukraine that would culminate in Trump’s first impeachment later that year. That overlap in timing matters when you consider that Dunphy’s lawyer, Justin Kelton, told MSNBC on Monday night that a former Giuliani associate named Lev Parnas was present for the exchange and could most likely corroborate the claim. Parnas was a key facilitator to the work Giuliani was doing in Ukraine to strong-arm the country into investigating Joe Biden and his son Hunter. Parnas eventually flipped on Trump and Giuliani during the first impeachment, handing over reams of texts, emails and other evidence to Congress.

But as my MSNBC colleague Jordan Rubin noted Tuesday, Dunphy isn’t the only person to have claimed that Giuliani was in the business of selling pardons. Roughly a year after he allegedly asked Dunphy about potential pardon recipients, Giuliani was reportedly part of a meeting at Trump International Hotel with a former CIA officer named John Kiriakou. Kiriakou told The New York Times that at one point while Giuliani went to the bathroom, one of his confidants said the former mayor could help — but “it’s going to cost $2 million — he’s going to want two million bucks.”

An associate of Kiriakou reportedly flagged the conversation to the FBI, but it’s unclear whether anything was done with the tip. At the time of the Times’ report, Giuliani “rejected the portrayal of events,” saying that “he had made clear that he did not work on clemency cases” because of his role as Trump’s attorney. He added that despite the large sums other lawyers were pulling in for their lobbying, “I have enough money. I’m not starving.”

It’s true that Giuliani is “not starving,” and at various points over the years he has been rolling in dough. But his post-mayoral pursuits of quick cash to support lavish spending have become the stuff of legend. When he ran for president in 2007, his net worth was north of $50 million, fueled in large part by the money he made giving speeches in the afterglow of his time as “America’s Mayor.” By the time Trump was in office, his consulting business had become a global affair, allowing him to rake in millions in contracts despite never having registered with the Justice Department under the Foreign Agents Registration Act. (Dunphy alleged that she offered to help him file that paperwork immediately before the pardons conversation; Giuliani allegedly declined, saying that “he was able to break the laws because, he said: ‘I have immunity.’”)

That money was spent almost as quickly as it came in, though. In divorce proceedings that began in 2018, a lawyer for his then-estranged wife, Judith Nathan, cited tax returns showing that Giuliani had “earned $7.9 million in 2016 and $9.5 million in 2017,” The Daily Beast reported in November 2018, while the former couple’s combined monthly expenses totaled about $470,000. On Giuliani’s end that included “$12,000 on cigars and $7,000 on pens” from April to August. According to The Washington Post, Giuliani’s lawyer claimed that his client “had to borrow money to pay taxes.”

Those same proceedings would also showcase how Giuliani would mix his quasi-governmental role with his own personal enrichment. While his work for Trump was technically pro bono, Nathan’s lawyer said in July 2019, “when he is going to work for the president, he bundles, for lack of a better word, clients who do have to reimburse him.” That included a trip that year to Warsaw, Poland, where Giuliani both gave a paid speech and met with Ukraine’s prosecutor-general as part of the Ukraine extortion plot.

As for Trump — whose campaign hasn’t commented on the allegations — he never shied away from making money during his time in office. Despite having handed over the keys to the Trump Organization to his adult children, he still sat at the head of the business, even as millions of dollars were funneled through his various properties courtesy of American taxpayers or foreign interests. Likewise, the wave of pardons he issued as he prepared to leave office, including 144 in his final 24 hours, seemed in many cases to be rewards for allies, including those who refused to testify against him in the Russia investigation. Whether these pardons were ever promised as payment for their silence seemed ripe for a second impeachment investigation even before the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol provided an overriding set of crimes for the House to charge him with.

If Dunphy’s allegations stand up in court, they should be a bombshell for Trump, who is the apparent front-runner to win his party’s presidential nomination again in 2024. But given everything else that the pair have managed to slough off, it’s just as likely that it wouldn’t even move the needle with Trump’s supporters. After all, a plan that would have Giuliani and Trump split the proceeds of a purchased pardon would be a more clear-cut case of corruption than their other schemes — but only slightly more damaging to the public trust than the other cons the two have run together.