Since the Reagan Revolution of the 1980s, conservatives have played a long game to capture the federal courts and undo the liberal constitutional order championed by the New Deal coalition. The Supreme Court demonstrated throughout its recently concluded term that it is working earnestly to bury the New Deal’s legacy once and for all. The Supreme Court’s decision on presidential immunity was a bungled mess that gives presidents a sweeping judicial shield from prosecutions if the president formally enlists other members of the executive branch to join criminal conspiracies and hamstrings prosecutors who might otherwise seek to protect the public from nonvirtuous chief executives. But throughout the term, the six-justice conservative supermajority — sometimes with assistance from the three-justice liberal bloc — was tremendously successful at hammering away at what little remains of a liberal constitutional regime.

The six-justice conservative supermajority was tremendously successful at hammering away at what little remains of a liberal constitutional regime.

Like clockwork, every summer when the Supreme Court winds down, legal professionals, political pundits and interested citizens bicker over whether the justices are politically motivated partisan hacks or whether they are serious, sober legal minds. These debates will inevitably lead to cries of “Do not politicize the Court” or “The Court is too political!”

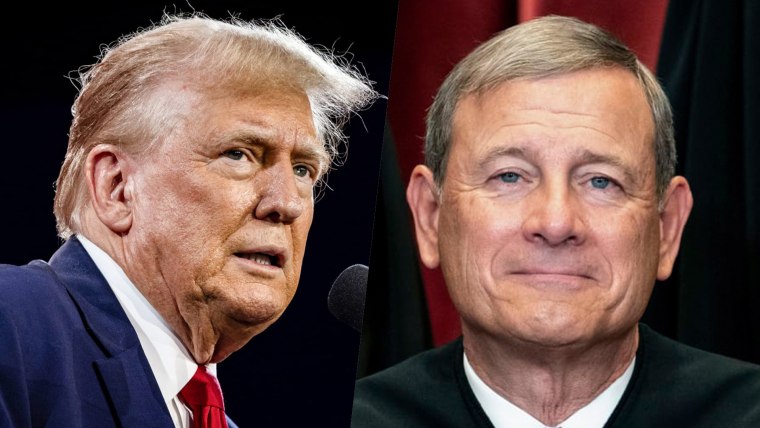

It’s all nonsense. The Supreme Court is, and always has been, political. In the 1950s and 1960s, the federal judiciary’s constitutionalism mirrored the values of the New Deal Coalition just as Chief Justice John Roberts' court is the living embodiment of the Reagan Revolution.

American constitutionalism between the mid-1930s and the 1970s endorsed an active role for the state. The federal government required durable power to provide basic welfare needs, intervene in social and political crises and provide pragmatic public policy prescriptions for the nation’s ills. The constitutional order valued the need for group-based mobilization, like organized labor and civil rights organizations, to protect individual rights. Constitutional law prioritized preserving liberal, democratic values in the middle of an era where such values were threatened by totalitarianism globally.

The rights revolution of the 1950s and 1960s was a core component of the radical democracy that American constitutionalism reflected, most notably in the Warren Court’s equal protection jurisprudence. Today’s constitutional law, steered by justices with deep ties to the Reagan administration, has a different trajectory.

Consider City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, where the Roberts Court held that it does not offend the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment for a city to enforce an ordinance banning homeless persons from using blankets, pillows or cardboard boxes while sleeping outdoors. The court roundly rejected the notion that a government has any obligation to provide basic needs for an unhoused person before subjecting them to the criminal justice system.

The court’s callous ruling treated some of our most vulnerable members of society as an eyesore who can be permissibly corralled and pushed into another jurisdiction rather than people to whom the public owes some basic duty of care.

While the court’s “let them eat cake” jurisprudence hurts those in dire straits, in Securities and Exchange Commission v. Jarkesy, the same court had little problem crafting new protections under the Seventh Amendment for white-collar criminals engaged in securities fraud. The court was also happy to apply lenient statutory interpretations of federal criminal statutes to the benefit of Jan. 6 defendants in Fischer v. United States, or elected officials taking bribes in Snyder v. United States. While the merits of any of these cases’ outcomes lie on a debatable spectrum, taken together they make the court’s callousness toward poverty all the more stark.

Women in need of emergency abortions in Idaho received a reprieve to have access to emergency care to save their lives without needing to be medevacked out of state, likely because a few justices feared the election-year consequences of such an anti-abortion ruling. In Moyle v. United States, the Biden administration argued that emergency room physicians can provide abortions to pregnant women in life-threatening situations under the federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act despite state abortion bans. The court punted because a few justices (Roberts, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett) appear to have gotten cold feet. The decision not to decide was to allow the conservative justices to temporarily save face before it rears its head against emergency abortions when the issue returns to them. Better yet for them, if former President Donald Trump wins again in November, the Trump administration will reverse the Biden administration’s EMTALA interpretation and the justices will be able to wash their hands of the question.

It was politics all the way down.

The federal government’s power to regulate also took blows this term. The administrative state took multiple hits in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, Corner Post v. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, and Ohio v. Environmental Protection Agency. The rulings in these cases, taken together, mean the federal judiciary has enhanced power to micromanage the promulgation of agency regulations that experts design to safeguard the American public.

The federal government’s power to regulate also took blows this term.

The court’s democracy docket fared no better. Trump v. United States, which resulted in the awful immunity ruling, and Trump v. Anderson, which said Colorado officials couldn’t use the 14th Amendment to remove Trump from the ballot — were disastrous for the rule of law and democratic norms. Many Americans are understandably distressed by the slow-paced criminal justice system that has yet to bring Trump to account for his efforts to overturn the 2020 election because they see his potential re-election as an existential threat to the constitutional order.

But those bemoaning the slowness of the criminal justice process have the Roberts Court to blame — the fits and starts of due process and regular legal order would matter little to the health of the body politic had the court not decided that Colorado officials have no power to remove insurrectionists from the presidential ballot, thereby neutering the purpose and meaning of the 14th Amendment.

The court’s decisions this term should serve as a reminder that the virtues of American constitutional law that liberals like to celebrate did not come out of the ether. Rather, they were the byproduct of victories at the ballot box and popular liberal ideals that set the basic conditions of governing for decades between the administrations of Franklin Roosevelt and Jimmy Carter.

If liberals want to combat the destructive aims of the conservative legal movement, now entrenched in the highest court in the land, then they will need to get serious about playing constitutional hardball and devise a meaningful political plan demanding institutional rearrangement and court reform.

Once and for all, it is time to disabuse people of the notion that the courts are impartial, apolitical arbiters of the Constitution. It’s never been that. And if Americans didn’t believe that before, the Roberts Court showed the public just that.