Article II, Section 8 of the Constitution states that before the start of a presidential term, the president “shall take” the oath of office, including a promise to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.” Four months ago, Donald Trump raised his right hand and for the second time swore that oath. On Sunday, he seemed to take it back.

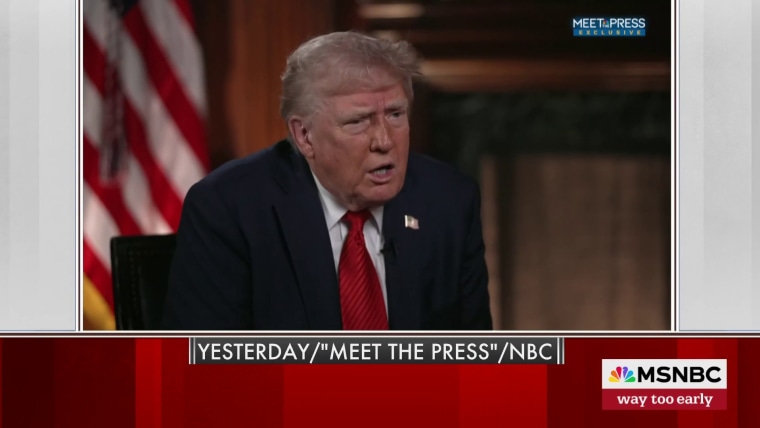

Once presidents are in office, it can be hard to determine if their conduct violates the oath. But in Trump’s extraordinary interview with NBC’s Kristen Welker, there was less opacity.

During a part of the interview dealing with his handling of immigration and his summary deportations of people to El Salvador, Welker asked Trump, “Don’t you need to uphold the Constitution of the United States as president?”

“I don’t know,” Trump replied. In an ironic twist, his waffling about his constitutional duties came the same day his former vice president, Mike Pence, received an award honoring his fidelity to the Constitution.

As is his custom, Trump shifted responsibility to an underling.

Trump’s uncertainty about the oath he’d sworn followed similar uncertainty about the Supreme Court’s recent decision regarding the Alien Enemies Act, when it unanimously reminded the administration that even people in the U.S. illegally have a right to due process of law. When Welker pressed him about whether “everyone who’s here, citizens and noncitizens, deserve due process,” the president again equivocated.

“I don’t know. I’m not, I’m not a lawyer,” Trump said. “It seems — it might say that, but if you’re talking about that, then we’d have to have a million or 2 million or 3 million trials.”

As is his custom, Trump shifted responsibility to an underling. “I’m relying on the attorney general of the United States, Pam Bondi,” he told Welker. “Because I’m not involved in the legality or the illegality. I have lawyers to do that … And they’re not viewing the decision the way you said it. They don’t view it that way at all. They think it’s a totally different decision.”

But the language of the court’s Alien Enemies Act ruling and the Constitution could not be clearer.

As the Supreme Court observed (in part quoting earlier rulings), it is “‘well established that the Fifth Amendment entitles aliens to due process of law’ in the context of removal proceedings....So, the detainees are entitled to notice and opportunity to be heard ‘appropriate to the nature of the case.’”

The Fifth Amendment says that “no person shall … be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” That the Constitution uses the word “person,” not citizen, means that it applies to everyone. A president who respects his oath of office would not need anyone to explain that.

The true threat to the country as we know it is a president who fancies himself a king.

Oath or no oath, none of that seems to matter to the president. As he told Welker, “If the courts don’t allow us to take people out, if we had to have a court case every single — think of it. Every single person, we have millions of people. If you have millions of court cases, figure two weeks a court case, it would be 300 years.”

Recycling his campaign rhetoric, he went on, “Many people have been killed, maimed, badly hurt by illegal immigrants that came over that are from prisons and from jails and from mental institutions. And they’re hurting our people. And if we don’t get them out, we’re not going to have a country for long.”

But the true threat to the U.S. as we know it is a president who fancies himself a king and can’t fathom that his first responsibility is to always uphold the Constitution. As Lawfare’s Ben Wittes and Quinta Jurecic wrote in 2017, “The presidential oath is actually the glue that holds together many of our system’s functional assumptions about the presidency and the institutional reactions to it among actors from judges to bureaucrats to the press. When large enough numbers of people within these systems doubt a president’s oath, those assumptions cease operating. They do so without anyone’s ever announcing. ... They just stop working — or they work a lot less well.”

Because the Constitution lacks a specific standard for whether a president has recanted the oath, it would be difficult for the courts to step in at this particular juncture. But George Washington, in his second inaugural speech, highlighted a different remedy if such a breakdown occurs. Washington assigned the ultimate responsibility to the people and their elected representatives for holding a president to the oath of office.

Referring to “this Oath,” Washington said, “if it shall be found during my administration of the Government I have in any instance violated willingly, or knowingly, the injunction thereof, I may…be subject to the upbraidings of all who are now witnesses of the present solemn ceremony.”

Sunday may have been the first day in American history that a president has ever expressed doubt about an obligation to uphold the Constitution. In our time, as in Washington’s, when a president expresses uncertainty about his constitutional duties, it is up to all of us to set him straight.