Growing up on the South Side of Chicago, I lived without fear as a little Mexican girl with a green card. Back then, Mexico had one-party rule. My family was so happy to be in the U.S., where it appeared to us that democracy was welcomed from the streets to the polling booths.

Even though the only person in my family who could vote was my father (he was fast-tracked for citizenship as a genius scientist at the University of Chicago), my mother, Berta, like me, was fascinated by democracy and all of its expressions. In fact, Mom took us out of school to go to a rally in support of Martin Luther King Jr. We felt safe with our green cards, my mom, two brothers and sister.

But the warning signs were there already.

Dad never forgot the disgust he felt on his first trip by bus to Chicago, when he had to choose which bathroom to use at the pit stop in Texas. He was light brown. Did he go to the “Colored” bathroom or the one with the “Whites Only” label?

I loved my new country even though I knew I was not entirely a part of it.

I was a year old when I arrived in the U.S. by plane with my mother and siblings, where an immigration agent noticed a rash on my body and told her I had to be quarantined. He suspected it might be measles. My mother knew exactly what the rash was. I was using a different blanket because mine had already been packed and shipped to Chicago and I had an allergic reaction to the material. Still, the agent insisted she leave me behind at the airport and continue on to Chicago without me. Mom, fierce and unyielding, pushed back hard, shouting that we had green cards and legal permission to be here. She was so loud and forceful that the agent backed down. That moment made clear: even a baby with legal documents was already viewed as a threat.

As a 6-year-old, I remember walking home from school with my Jewish bff, calmly making plans about which basement her family and mine would hide in if George Wallace was elected president. We didn’t have Instagram or TikTok back then, but we knew that Wallace did not like Mexicans or Jews.

On our family’s annual road trips to Mexico, I always dreaded when the border agents approached our car as we crossed back into the U.S. They would search our station wagon meticulously. Why did they search our car but not those of the white Texas folks who were driving home too?

Still, I felt safe. I loved my new country even though I knew I was not entirely a part of it.

In truth, immigrants have never really been safe here. And that’s what our country needs to accept right now. In the first few months of Donald Trump’s second administration, we have witnessed an aggressive scrutiny of people who speak out against the administration, including an onslaught on student activists. Mahmoud Khalil, a student activist at Columbia University and a green card holder, was seized by ICE agents at his home in March. The Trump administration claimed his pro-Palestinian activism on campus constituted antisemitism and argued that his continued presence in the U.S. could have “potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences,” citing an obscure provision in immigration law. He’s currently fighting the case from detention.

Columbia student Yunseo Chung, who has legal permanent residency and has lived in the U.S. since she was a child, is suing the government to block her deportation after the government issued an administrative warrant for her arrest and deportation, citing her activism for Palestinian rights. Mohsen Mahdawi, a Columbia student and green card holder, was detained by ICE when he arrived at his interview to obtain his American citizenship, allegedly for his activism in the pro-Palestinian movement on campus. He has since been released by a federal judge in Vermont on conditions. And there are others.

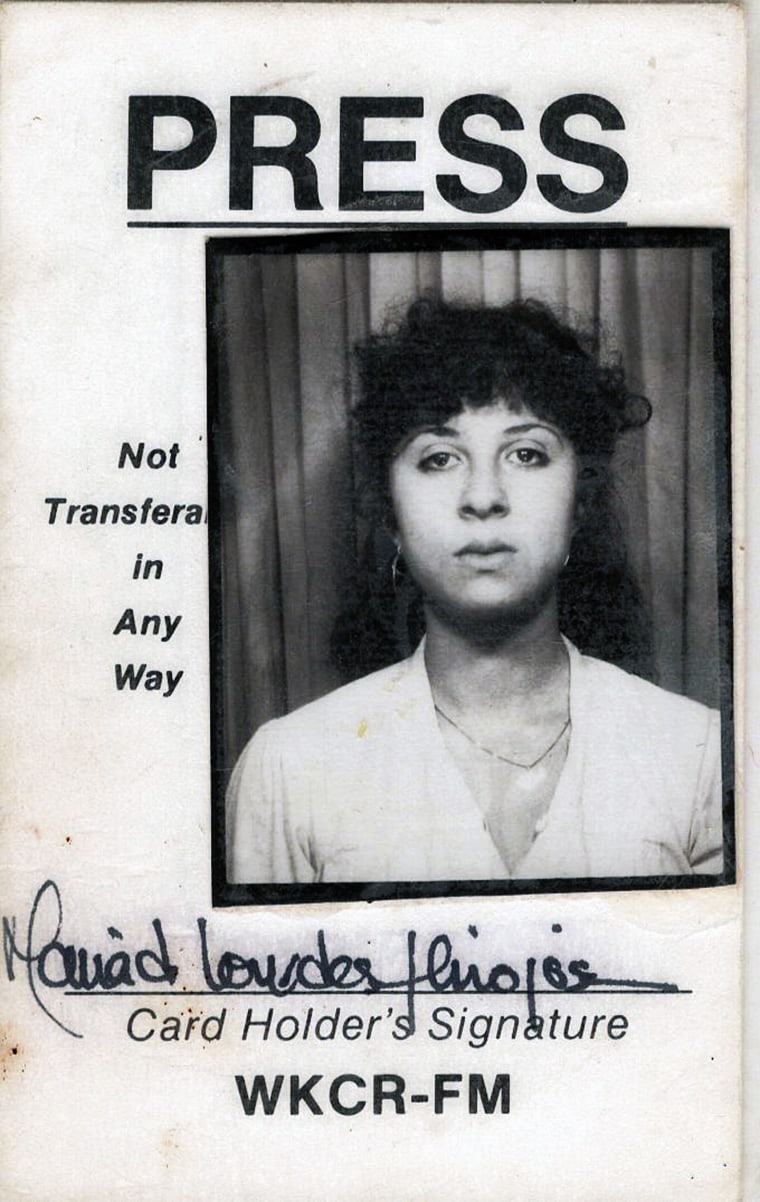

It wasn’t until college that I began to understand the risks of being a student activist with a green card. I chose Barnard College, Columbia’s sister school (back when Columbia was still all men), because I wanted to study theater and politics. I was never arrested or detained. On some level, I knew that if you are political and an immigrant without citizenship, you are not entirely safe — although I never feared I’d be detained in my home and given deportation orders.

Still, as a student activist in the 1980s, I attended many protests.

I took part in rallies against Columbia and Barnard’s investments in apartheid South Africa. Several years later, then-student Barack Obama and dozens of other students took over Hamilton Hall, furthering the call for divestment. For three weeks, the door remained chained shut. But the NYPD was never called on campus.

I have taught students who are immigrants or undocumented; they live in fear of being hunted by ICE, when all they want is to study.

In 1983, Barnard College awarded its medal of honor to Jeanne Kirkpatrick, a war hawk who played a key role in funneling millions of U.S. taxpayer dollars to support an anti-democratic, oligarchy-blessed Salvadoran government and its fight against leftist guerrillas supported by Jesuit Catholic priests aligned with justice for the poor. El Salvador was in the headlines every day back then. This was the same government that stood by when Archbishop Oscar Romero was gunned down while giving a sermon, when four American nuns were raped, murdered and their bodies left by the side of a road. Innocent people were being killed there with bombs paid for by U.S. taxpayers.

We protested on campus and demanded that Barnard rescind the award. The media caught wind of our efforts and suddenly we, as student protesters, were being portrayed as the ones trying to limit free speech. The protests made national news, and I even appeared on "Nightline" for an interview. It never crossed my mind to stay completely silent, because I had a green card. In the end, Barnard decided to rescind the medal.

Everything I’ve achieved in this country — being the first Latina in many of the newsrooms I worked in, from NPR to CNN, founding Futuro Media, a thriving, now 15-year-old independent media company, all the awards and recognition — would likely have never happened if I had lived in Trump’s world. According to the current operating logic, as a student on a green card, I could have been swept up and threatened with deportation at any moment.

By the late 1980s, I had moved away from activism entirely and become a journalist. My work took me to places the U.S. government viewed with suspicion — places such as Cuba and Nicaragua. Becoming a citizen felt like the smart thing to do if I wanted to continue my work as a journalist, which entailed ruffling the feathers of the powerful.

In 1989, I took the oath to become an American citizen. By then, I had come to understand that my green card left me vulnerable to the whims of immigration agents, especially at the border. I had already lived through it once, when the agent tried to take me away from my mother at the airport as a baby, despite our green cards. That moment stayed with me. It reminded me that my legal status offered only limited protection. And so, I became a citizen because I knew I needed to protect myself.

As a journalist, I’ve won the most prestigious awards in the industry — a Pulitzer, Peabody, four Emmy’s, the Murrow and Cronkite awards — and now I’m a distinguished journalist in residence at my alma mater. But decades ago, I was not so different from the students today who are being removed from campuses and protest sites, disappeared in broad daylight, simply for expressing their views and standing up for justice.

The students I teach at Barnard now are scared. I have also taught students who are immigrants or undocumented; they live in fear of being hunted by ICE, when all they want is to study.

Recently, I’ve been contemplating that saying I used to hear as a kid in Chicago from friends in the Black church: “There but for the grace of God go I.” My students aren’t the only ones frightened, though they tell me they’re not giving up or giving in.

I’m frightened, too. For Mahmoud Khalil, Yunseo Chung, Mohsen Mahdawi and so many others. Because once, not so long ago, I was them. A student who wanted to change the world for the better, who happened not to be born in the United States.