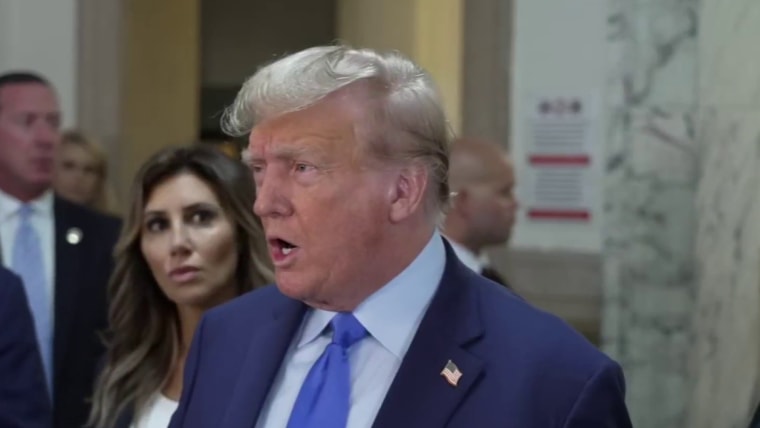

Donald Trump’s combative testimony was the headline on Monday in his fraud trial in New York state court. He called Attorney General Letitia James a “political hack,” complaining “the fraud is her.” Outside the courtroom he protested that Judge Arthur Engoron “ruled against me, and he said I was a fraud before he knew anything about me.”

Since Trump had already been railing against the case outside the courtroom, it shouldn’t have surprised anyone that he was on the attack inside of it. Perhaps the only surprise is that Trump’s attorneys have been getting in on the act too.

There’s no ethical rule that requires lawyers to argue their case to the press while the court is on a break.

And to be clear, I’m not talking about the fireworks in court. Defense counsel Christopher Kise and Alina Habba have frequently and bitterly argued with Engoron throughout this trial. But in the courtroom, attorney comments should be judged by a different, more permissive standard. The rules of professional responsibility require attorneys to be zealous advocates for their clients. That means sometimes pushing the limits with the judge while court is in session.

There’s no ethical rule that requires lawyers to argue their case to the press while the court is on a break, however.

Actually, it’s usually in the interests of both civil and criminal defense attorneys in high-profile cases to simply say “no comment” as they hurry to and from the courthouse. The traditional thinking is that there’s no reason to unnecessarily irritate the judge or the other parties.

Trump’s attorneys have taken a different approach. They visibly stand behind Trump when he speaks outside the courtroom. They watch as he lambastes the court and the attorney general, lending what appears to be their tacit approval.

But Trump’s attorneys are also doing their own talking to the press.

Kise told reporters after Trump’s testimony on Monday: “In my 33 years, I have not had a witness testify better.” Kise is an accomplished lawyer. I have to imagine there’s been an expert witness or two in his career who has testified better than Trump. But there’s nothing wrong with a little hype about one’s client. Whether or not it’s believable, the praise doesn’t compromise the client or disparage any of the trial participants.

Habba, on the other hand, has more closely followed her client’s playbook.

Habba shouldn’t personally attack the judge. But is she technically doing anything wrong?

In statements to the press, Habba has called Engoron “unhinged.” She has said she will not “tolerate” what the judge is doing. She said she is “seeing” at this trial “a demise of American judicial system and democracy.”

Obviously, Habba is doing something most lawyers don’t do. She shouldn’t personally attack the judge. But is she technically doing anything wrong?

I don’t blame a lawyer for getting frustrated with a judge during trial. Sometimes it can feel like a judge is firmly on the adversary’s side. Sometimes a lawyer feels a judge just doesn’t like him or her. I’ve felt this way plenty of times. I know most of the time I’ve overreacted or been too sensitive. A few times, though, I still think I was right.

And Trump’s lawyers may very well believe Engoron has already formed an opinion about the case. That’s because Engoron has literally already issued an opinion on the case: a scathing 35-page judicial opinion ruling against the defendants, finding that they committed fraud and granting summary judgment. This case is proceeding before the same judge who issued this opinion, and not a jury. It’s fair to think that the judge might come to the case with some preconceived notions.

But calling Engoron “unhinged” invites complaints from members of the legal community. Even if it’s protected speech, all it takes is one person to file an ethics complaint.

In fact, an outside observer, completely unconnected with the case, has already filed an ethics complaint in Trump’s civil fraud trial. Except, it’s against the judge. Republican Rep. Elise Stefanik, a Trump ally, filed an ethics complaint against Engoron on Friday. There are three takeaways from this development: One, anyone can file an ethics complaint against a lawyer or a judge. Two, ethics complaints are a huge headache for lawyers and judges, even if they are completely unfounded. But three: If a judge or lawyer is really out of line, an ethics complaint is procedurally a better route than a press conference.

When it comes to making comments to the press, I would have made different choices than Trump’s attorneys. I might have some unkind thoughts about a judge. I might even share those thoughts privately with my team. I would not publicly call a judge “unhinged.” But maybe Trump and his lawyers have already written this case off. If they think the case is lost anyway, then perhaps they figure their efforts will be perceived by Trump supporters as righteous resistance.