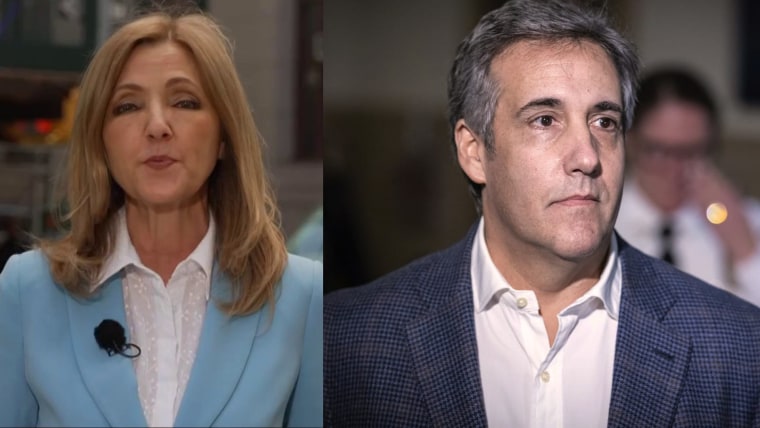

Michael Cohen is finally off the stand.

The former fixer and attorney for Donald Trump spent several days on the witness stand in the former president’s New York criminal trial, finally ceding the chair on Monday.

The prosecution’s direct examination of Cohen ranged from serviceable to successful. The cross-examination of Cohen by defense attorney Todd Blanche drew more scrutiny.

Some of the criticism of Blanche was warranted. Some was not.

It’s true that the defense’s cross-examination was too long. But, in defense of the defense, I very much understand why.

It’s true that the defense’s cross-examination was too long. But, in defense of the defense, I very much understand why. Blanche is trying the biggest case of his career. He was taking on a witness with a long history of dishonesty and criminal activity. He had millions of Cohen’s own words at his fingertips, from books to podcasts to recorded live appearances. There was just so much material to work with. Marshaling the facts into an outline on a yellow legal pad must have been a daunting task. Worse than that, though, is the fear of leaving something out.

As much as lawyers claim to understand juries, we don’t understand them much at all. When lawyers stick around after a trial to talk to jurors, they are always surprised at how the jurors saw the case and the evidence. There’s always some unexpected fact that the jury focused on — and in my experience, it’s often a fact that the lawyers considered unimportant. So, all lawyers fear leaving anything out of a cross-examination. It might be just the one thing that would have resonated with that last holdout juror.

And it only takes one person to avoid a guilty verdict.

That’s why Blanche’s cross erred on the side of epic. And it’s easy for lawyers like me to just say a cross should be tighter, shorter and more surgical. But I’m not trying the case. Do you want to be remembered as the lawyer who didn’t ask enough questions? Or the lawyer who maybe asked a few extra questions, and got lucky with the last one?

And indeed, while probably longer than it needed to be, the defense’s cross did land a few hits. Of the two most consequential moments, the first cast doubt on Cohen’s claim that he made a phone call in late October 2016 updating Trump on the Stormy Daniels payment and the second was when Cohen admitted he stole $30,000 from the Trump Organization.

While there was a lot of attention paid to the back-and-forth over Cohen’s October phone call, I don’t think it really was that big a blow to the prosecution. It could be, if the jury concludes Cohen lied about this point and chooses to disbelieve his entire testimony. But the jury might alternatively just chalk this contradiction up to memories naturally fading after eight years.

I think the second concession was more significant. Cohen stole $30,000. From the Trump Organization. Cohen has already admitted to being a criminal and to hating Trump. So what’s one more (unprosecuted) bad act on cross? In short, it’s a big deal.

First, this is something the state should have addressed in their own direct. But second, the prosecution has painted Cohen as a bumbling, delusional, tragic figure, whose major sin was a misguided loyalty to his hero and eventual betrayer, Trump. It was a good strategy. But Cohen’s admission that he stole from his hero cracked the prosecution’s image of Cohen. Now, he’s just an opportunistic thief, who would steal from his own employer. That sounds more like the behavior of a sociopath than a loyal employee.

And we should look for the defense to focus on this contrast in its closing. They will argue that if Cohen is willing to steal from Trump, why wouldn’t he lie about Trump?