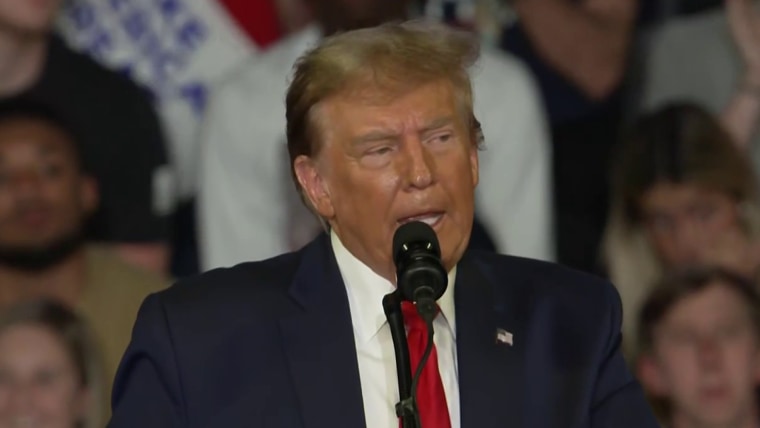

Former President Donald Trump, the presumptive GOP presidential nominee, hasn’t said a lot about Russia’s war in Ukraine, the biggest international news story before Israel’s war against Hamas in Gaza shoved it off the front pages. When Trump does mention the conflict, he tends to keep his comments extremely vague. At times, they’re contradictory.

The day before Russia’s full-scale invasion more than two years ago, for instance, Trump called Russian President Vladimir Putin “genius” and “savvy” for declaring Ukraine’s Donbas region independent and using it as a pretext to send Russian forces in. Weeks later, once the invasion was in full swing, the former president was more morose on Putin: “Now, a lot of things are changing. … This doesn’t seem to be the same Putin that I was dealing with.”

Are there problems with Trump’s reported land-for-peace idea? No question. But as the war goes on, the realistic alternatives are becoming more difficult to spot.

But through it all, Trump has been consistent on one thing: The war should end sooner than later, ideally immediately. During a May 2023 CNN town hall, he stated that he wanted Russians and Ukrainians alike “to stop dying” and that striking a deal was the only way to do it. He has bragged repeatedly that he could hammer out a peace deal in 24 hours, even as he refuses to articulate his strategy for pulling off such a feat.

We now possibly know more details of Trump’s proposed Russia-Ukraine strategy, as reported by The Washington Post over the weekend. The Post cites people who discussed the plan with Trump or his advisers, who spoke on the condition of anonymity about confidential conversations and suggest Trump would plan to push Ukraine to hand over control of Crimea and the Donbas region to Russia in any future settlement, in effect codifying the gains Putin has made in his illegal invasion. In return, Putin would have to stop the war for good.

The Washington Post report was met with a flurry of criticism. Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., a Trump ally, said he was opposed to giving Russia land. The rumored plan raised eyebrows in Kyiv as well, with one former Ukrainian interior ministry official arguing that giving Russia a “face-saving” way out meant destroying the very post-World War II rules-based order the U.S. and its allies claim to defend. Even Robert Reich, President Bill Clinton’s former secretary of labor, piled on: “Did we learn nothing from WWII and the danger of appeasement? Give an inch, he’ll take it all,” he posted on X. Trump campaign adviser Jason Miller blasted the Post report as fake news.

Are there problems with Trump’s reported land-for-peace idea? No question. But as the war goes on, the realistic alternatives are becoming more difficult to spot.

Such measures would certainly not be welcome in Kyiv. Ukraine, for one, scoffs at the notion that formally gifting Putin a chunk of its territory would result in a long-term peace. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has argued that any cease-fire would only benefit Russia in the end, allowing it to recuperate and rebuild before the inevitable counterattack. Last summer, during the beginning of Ukraine’s counteroffensive in the east, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen stated that cease-fires with Russia are only short-term aberrations rather than a true peace. Zelenskyy himself has been outright dismissive of Trump’s “I can solve it in 24 hours” boast, all but telling him to visit Kyiv so he can receive an education.

You can’t blame analysts and world leaders — anybody, really — for rolling their eyes at this specific peace formulation, at least in today’s circumstances. The practicalities of negotiating it, yet alone implementing it, are extremely challenging. The Ukrainians are still very much committed to their own 10-point peace plan, first unveiled by Zelenskyy in November 2022, that demands a full Russian troop withdrawal from every inch of Ukrainian territory, a justice mechanism to prosecute Russians for war crimes, security assurances from the West and compensation for damages. Ukraine’s inability to gain any more ground over the last 18 months hasn’t changed this position in any notable way. On the other side, Putin, his power solidified at home after a stage-managed “election” last month, is in no mood to negotiate at a time when the Russian army is engaged in several counteroffensives along the 600-mile-long front line and weeks after Moscow experienced its biggest territorial victory in nearly a year.

Trump’s purported plan leaves even more to be desired. Russia, for example, doesn’t control all of the Donbas, which means that for the scheme to work, Ukraine would have to voluntarily withdraw from the entire region after spending two years trying to liberate that very same stretch of land. To be blunt, this is as likely as Putin waking up one morning and deciding to withdraw Russian forces from Crimea. Zaporizhzhia and Kherson, two entirely different provinces, would apparently be given back to Ukraine, requiring a Russian troop pullout there. The whole thing is almost too delusional to entertain. There are also other factors U.S. policymakers would have to consider if they operationalized such a plan. How would China, for example, react to a situation whereby Russia was in essence rewarded for its aggression? How could the West be certain that Putin wouldn’t try to push farther west a year or five years down the line?

Trump, as hard as it is for some to admit, is probably correct that a settlement will have to be explored sooner or later.

Yet as deficient as the plan may be — and let’s be clear, “plan” might be too strong a word — it’s increasingly likely that some kind of diplomatic settlement will need to occur to end the war. While even this baseline observation will strike a chord with some of Ukraine’s backers, it’s increasingly evident that the war won’t terminate with a wholesale victory by one side or the other. There won’t be a surrender signing ceremony aboard an aircraft carrier akin to imperial Japan’s declaration of defeat in September 1945. The U.S. and its allies in Europe seem to recognize this, although they remain hesitant to pressure Ukraine into a diplomatic process its own leaders aren’t ready to explore.

Trump, as hard as it is for some to admit, is probably correct that a settlement will have to be explored sooner or later. As it stands today, neither Ukraine nor Russia has the military capacity for a full victory. The days of big territorial breakthroughs like Ukraine’s September 2022 counteroffensive in the Kharkiv region are likely over. The conflict is bleeding both sides. U.K. military intelligence estimates that Russia has sustained an average of 638 casualties a day over the last two years, recently having lost 913 men every day through March.

The Ukrainian army is doing the best it can with the limited resources at its disposal, but even if another assistance package clears Congress, it won’t mitigate its manpower issues. Those whose patriotic fervor led them to rush the enlistment offices in the first weeks of the war are now dead, injured or still in the trenches, which means Zelenskyy will need to dip deeper into the Ukrainian population to fill the ranks as soldiers rotate out. This was made worse by last year’s failed counteroffensive, the results of which were at best crumbs on a map that is hard to differentiate from one month to the next.

So critics may scoff at Trump’s reported “plan” all they want — but when it comes down to it, a diplomatic agreement that is “good enough” for both sides is one of the more realistic avenues to pursue. The only question is how exhausted Ukraine and Russia will become before pursuing it.