Walgreens’ announcement Tuesday that it plans to shutter 1,200 locations over the next three years made headlines, but that doesn’t mean it was a surprise. The company is losing money and indicated a significant closure announcement was coming this past summer.

And among pharmacies large and small, Walgreens is not the exception; it’s the rule. CVS announced it would close 300 locations earlier this year. Rite-Aid has shut down hundreds of locations since filing for bankruptcy in 2023. Independent pharmacists face an existential crisis, with many saying they are struggling to keep their doors open. In the first eight months of 2024, more than 2,000 pharmacies across the U.S. closed, according to research conducted by Ben Jolley, a fellow at the American Economic Liberties Project (where, disclosure, I am on staff). That number is almost evenly divided between independent pharmacies and corporate chains, with rural America hit particularly hard.

Fewer people are turning to visiting big-name pharmacies than they did in the past.

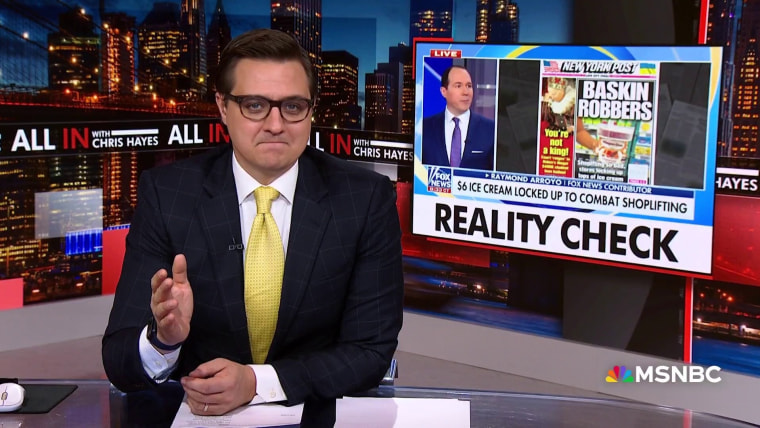

The woes facing pharmacies have little to do with either shoplifting or stores locking up products to prevent shoplifting. Walgreens and other pharmacies’ struggles reflect the financial headwinds besetting the sector, which is reeling under the combined pressure from pharmacy benefit managers, changing consumer retail habits and, when it comes to the giant corporate chains, disastrous expansions.

Pharmacies traditionally earn money in two ways. The first is the obvious one: filling prescriptions. But that model is increasingly under threat. A major culprit? Pharmacy benefit managers, also known as PBMs. These companies originally intended to save patients and insurers money by negotiating discounts from manufacturers on medications. But more recently, they have been snapped up by larger and larger conglomerates. As they consolidated — the three largest PBMs handled almost 80% of all prescriptions issued in the U.S. in 2023 — they steered business toward favored pharmacies (including ones they owned) and mail-order facilities.

This business model has become unsustainable. “PBMs hold the whip hand over the whole industry, whether it be Walgreens or the independent pharmacies,” Jolley told me. Corporate consolidation has softened the blows for the big chains: CVS owns Caremark, the nation’s largest PBM, while Walgreens works with Express Scripts, the nation’s third-largest PBM. But rising pharmaceutical prices, often driven by PBMs, have driven customers to low-cost mail-order services like Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drugs for their generic drugs. At the same time, PBMs squeezed reimbursement rates to a point that many independent pharmacies allege — and the Federal Trade Commission concurs — they are frequently filling prescriptions at a loss.

Then there's the other source of revenue pharmacies traditionally relied on: sales of snacks, over-the-counter drugs like cough medicine, and personal hygiene staples like shampoo and tampons. The idea was that a customers coming in for prescriptions could pick up needed rolls of toilet paper while they were at it. This model worked — until customers mass embraced online retail shopping, which combines lower prices with greater convenience. Moreover, many PBMs require patients to use mail-order for ongoing or specialty prescriptions — which means they aren’t coming into the store at all.

It’s true that locking up products like toothpaste in reaction to fears of a shoplifting epidemic probably didn’t help matters. And yes, those fears were overhyped. (Don’t take my word for it. Walgreen’s c-suite says the same.) But the bigger issue was that fewer people are turning to visiting big-name pharmacies than they did in the past. While the public was being fed viral smash-and-grab shoplifting videos, it was increasingly obvious to stock market and health care analysts alike that the big pharma giants’ own wretched business decisions contributed to their well-reported financial problems. Think of it this way: They became too big not to fail.

None of this is what the doctor ordered.

Rite-Aid’s bankruptcy was caused, in part, by large amounts of debt from ill-advised mergers with rival chains like Eckerd’s, not to mention the pressure of more than 1,000 lawsuits accusing the company of fueling the opioid epidemic. CVS turned itself into a conglomerate, using its Aetna insurance arm to drive business to its medical clinics — but didn’t count on the fact that increased medical costs would so cut into the profits of its insurance offering that it would begin to drag down the entire business. As for Walgreens, it also attempted to move into primary care, an expensive — and so far less than lucrative — proposition.

When it comes to pharmacies and PBMs, bigger is most certainly not better. It’s unhealthy for patients, customers and the greater medical ecosystem, not to mention the companies themselves, from Walgreens right down to the smallest local pharmacist. None of this is what the doctor ordered.