The Trump years were very different experiences for the Republican leaders in Congress. Kevin McCarthy of California, the GOP leader in the House, rushed to embrace President Donald Trump, using him as a shield from the kind of criticism on the right that doomed his two most recent predecessors. Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, who heads the Senate GOP caucus, preferred to use Trump as a weapon in his long-game goals, reshaping the federal judiciary with conservative nominees and overhauling the tax code but otherwise keeping the White House at arm’s length.

For a brief moment, The New York Times reported Thursday, McCarthy and McConnell fell into full alignment on Trump. In the days immediately following the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, both men reportedly expressed the belief that Trump was at fault for the assault and that he couldn’t be allowed to remain in power. But their anti-Trump stances collapsed in the face of opposition from their members. Their backtracking is a display of failed leadership that should be shocking — but it’s actually a reminder of how McCarthy and McConnell got to the top in the first place.

Their backtracking is a display of failed leadership that should be shocking — but it’s actually a reminder of how McCarthy and McConnell got to the top in the first place.

The Times’ story was adapted from the coming book “This Will Not Pass: Trump, Biden and the Battle for America’s Future,” by Alexander Burns and Jonathan Martin. According to them, McConnell and McCarthy were more forceful in their private denunciations of Trump than they were in public — at least in the first days after the attack.

Burns and Martin on Thursday night provided MSNBC with a recording of a meeting McCarthy held with the House Republican leadership team on Jan. 10, 2021. In the audio clip played on Rachel Maddow's show, Rep. Liz Cheney, R-Wyo., then the third-ranking member of the GOP caucus, asks McCarthy whether Trump would ever consider stepping down. McCarthy responds that he hasn't spoken with Trump in several days but that he is considering calling him and suggesting that in the face of a second impeachment he should resign.

"Now, this is one personal fear I have," McCarthy told Cheney. "I do not want to get into any conversation about Pence pardoning. Again, the only discussion I would have with him is that I think this will pass, and it would be my recommendation you should resign.”

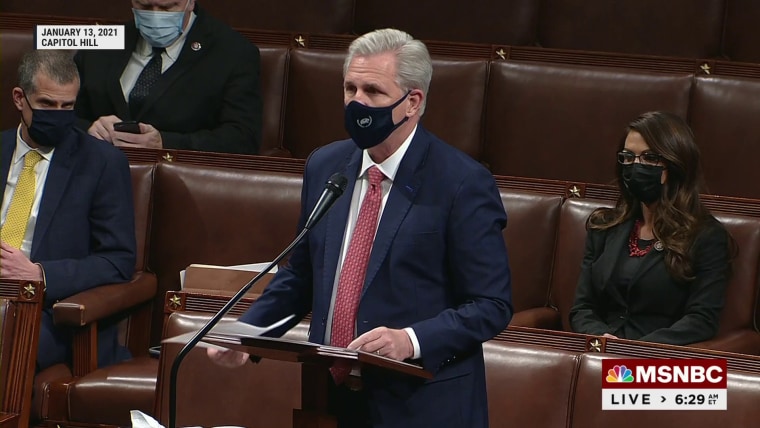

While McCarthy voted against the article of impeachment against the president, he did say on the floor of the House on Jan. 13, 2021, that Trump “bears responsibility for Wednesday's attack on Congress by mob rioters,” adding, “He should have immediately denounced the mob when he saw what was unfolding."

Meanwhile, according to The Times, McConnell was closer to supporting convicting Trump in a second impeachment trial than was believed earlier. McConnell, who is normally adept at nose-counting within his caucus, predicted a bipartisan vote to convict Trump. “If this isn’t impeachable, I don’t know what is,” he reportedly told advisers.

But neither man stepped up when it counted. With Trump’s Senate impeachment trial still looming, McCarthy visited Mar-A-Lago and was pictured next to a smiling Trump. He then worked to excommunicate Cheney from her leadership role for the sin of not backing off the position that McCarthy had once held. McConnell, likewise, went from a possible yes vote to supporting Trump’s acquittal. Then, seeing the political danger it represented, both worked to derail a bipartisan deal in the House for an independent inquiry into the attack.

He may now have the title “minority leader,” but there’s little that McCarthy can get members of his caucus to do that they wouldn’t already be doing in his absence.

One thing I’ll say about McCarthy and McConnell alike is that they know how to tell which way the wind is blowing within their caucuses. McCarthy has managed to hold on to his spot atop the House GOP by refusing to crack down on his pro-Trump members even as they spread lies, attend white supremacist conferences and face federal indictment. He may now have the title “minority leader,” but there’s little that McCarthy can get members of his caucus to do that they wouldn’t already be doing in his absence — and he isn’t exactly looking for opportunities to change that dynamic.

McCarthy issued a statement Thursday afternoon, before the audio of his conversation with his leadership team was released, saying The Times’ report was “totally false and wrong.” Tellingly, he made sure to wrap praise for Trump into his message, lest he be attacked by his own members for being insufficiently loyal to the man who still wants to be kingmaker in the party. (We'll see how well that worked now that we've heard exactly what McCarthy was saying behind closed doors.)

McConnell, too, has made his mark on the Senate through the path of least resistance. He is guaranteed to always choose whatever option maintains power for the Republican Party. He’s shown the GOP the power of unity in opposition to a Democratic president and been personally willing to take the hit for standing against popular policies that would give Democrats any sort of edge.

In addition to his reputation as a master of strategy and tactics in the Senate, “McConnell has a brilliant grasp of his caucus members’ needs, and he helps them protect their seats with tens of millions of dollars in campaign donations and federal grants,” The New Yorker’s Jane Mayer wrote in a 2020 profile. “McConnell also lets his caucus members take the spotlight, and, when he can, he allows them to skip votes that will be unpopular with their constituents.”

“I didn’t get to be leader by voting with five people in the conference,” McConnell, according to The Times, told a friend about his change of heart over convicting Trump. It’s no wonder, then, that he’s managed to hold on to power longer than any other GOP Senate leader, a streak that shows no sign of ending any time soon.

This time around, though, their willingness to follow instead of lead has left McCarthy and McConnell in far weaker positions than they’ve maintained by guarding their own backs. It’s impossible to know how many votes McConnell and McCarthy may have swayed if they’d showed the courage of the convictions they reportedly aired in private and backed Trump’s impeachment and conviction. It would have been nearly impossible to hit the two-thirds majority required in the Senate to convict Trump, but it’s clearer than ever before that McConnell never even tried.

A convicted Trump would be barred from running in 2024, unable to use his campaign infrastructure to raise the vast sums of money he’s accumulated since his second acquittal. That in turn means that whether McCarthy and McConnell are leading the majority next year still comes down to their candidates’ support from Trump. This continued relevance has also allowed Trump and his allies to continue to lay the groundwork to re-install Trump in the White House, even if he doesn’t get enough votes.

It was McConnell and McCarthy’s members who were threatened by a mob intent on converting Rudy Giuliani’s conspiracies into an actual subversion of the democratic process. And yet they have shown no willingness to speak up as Trump continues to keep the embers of Jan. 6 stoked and ready to erupt again. A craven, venal need to ensure their own political survival is clearly much more important to them than the survival of our democracy.