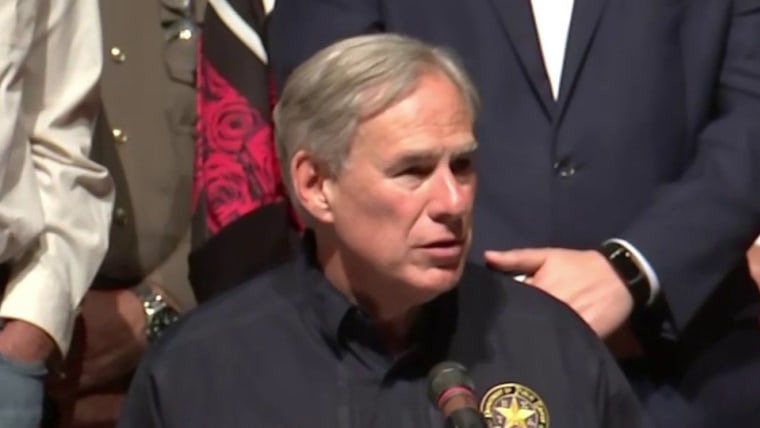

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott last week said that Salvador Ramos, the gunman in the shooting that left 21 dead at Uvalde’s Robb Elementary School, had a "mental health challenge" and the state needed to "do a better job with mental health."

Abbott was repeating a common refrain that has developed among Republicans when asked for a response to a new mass shooting. Mental illness causes gun violence, they say, and gun control will not prevent another Uvalde, or any of this year’s other 212 mass shootings as of Friday, a number that's only increased since then. But placing the full blame on mental illness both nullifies concerns that the violence could be prevented through gun policy reform while validating calls to expand access to firearms in the interest of self-protection.

At least, Abbott is consistent. He used the same exact phrases after the 2018 mass shooting at Santa Fe High School, which left 10 dead and another 13 wounded. (He then went on to cut $211 million in funding to the state’s department that oversees mental health and overall loosen gun laws in Texas.)

Using Abbott’s framing, the mere suggestion of mental illness becomes the deciding risk factor for firearm violence instead of what it really is: a medical condition just like heart disease, cancer or diabetes. Furthermore, the suggestive psychiatric diagnoses floated by the media, laypeople and (the worst offenders) politicians in all parties only serve to obfuscate the incredible complexity behind gun violence. Worse, these assumptions often parallel many other societal stereotypes regarding race, gender and socioeconomic status.

The root causes of any type of gun violence are complex and often associated with additional risk factors that correlate more strongly than mental illness alone. Studies show that alcohol and drug usage increase the risk of violent crime by as much as sevenfold, even among persons with no history of mental illness. Yet, Texas is one of 21 states that now allow for an individual to walk into a bar with a fully loaded concealed gun. Other predictive factors for gun violence include a history of childhood abuse and identifying as a man, but I don’t hear lawmakers asking for all men to receive a gun violence-related restraining order at birth.

Complicating matters even further are the documented psychiatric diagnoses of well-known mass shooters. The gunman in the Aurora, Colorado theater shooting that left 12 dead and 58 wounded, had been seeing a psychiatrist for mental illness prior to the shooting. Dr. William H. Reid, one of two court appointed psychiatrists ordered to evaluate him stated that mental illness played a role in his crime but what led him to commit mass murder “lies in an unimaginably detailed and complex confluence that we can’t replicate because we can’t see all of it.”

Additional assumptions around mental illness and gun violence place the burden for any solution on the ability of mental health professionals, law enforcement and/or family members to predict who might be likely to commit an act of violence with their firearm. “Red flag laws” which allow for family members, law enforcement and, in some states, school officials to file for a protection order against firearms owners are necessary but not sufficient by themselves. Identifying persons at high risk for gun violence is a bare minimum, yet it does nothing about ease of access of such weapons, particularly assault weapons.

Case in point: A groundbreaking registry with rare bipartisan support in California for persons deemed too dangerous to be armed has been a failure. Evaluators cited numerous breakdowns in communication, such as the lack of coordination of firearm relinquishment orders between courts and local justice officials, as well the lack of sufficient staff to recover weapons.

The urge to draw a connection between mental illness and mass shootings seems to come from a need to associate the shooter with the most extraordinary and rare features of society. It’s a way to make sense out of something utterly incomprehensible. In this worldview, anyone who shoots children in cold blood leaving bodies unidentifiable outside of DNA testing must be insane and sick, in other words not like any of us. This reflexive rejection makes a certain kind of sense, but it absolutely should not translate into neglecting that America has a gun problem.

We now live in an era in which pandemics, racial inequality, sequential grief and lies fed by social media are widespread. We have also seen a proliferation of gun crimes leading to firearm violence as the leading cause of death amongst children and adolescents in 2020. The cosmetic theater of blaming Uvalde and countless lost lives on mental illness may keep politicians in office and the National Rifle Association’s campaign dollars flowing, but so will the blood spilled by inaction and cowardice.