It was two weeks ago yesterday when Donald Trump and his hapless band of lawyers made a curious pitch: They asked a federal judge to order the appointment of a special master to oversee the handling of the documents that’d been seized two weeks earlier in the Mar-a-Lago search.

It was an unpersuasive request, presented in an unfortunate way. Orin Kerr, a conservative law professor at UC Berkeley, noted that many actual lawyers were “giggling at Trump’s motion, and how poorly it was done.”

Former Attorney General William Barr, a former Trump ally, was asked for his opinion about the argument for a special master. “I think it’s a crock of s---,” he said, adding, “I don’t think a special master is called for.”

That may have been the consensus view among legal experts, but it was not the view that prevailed. NBC News reported:

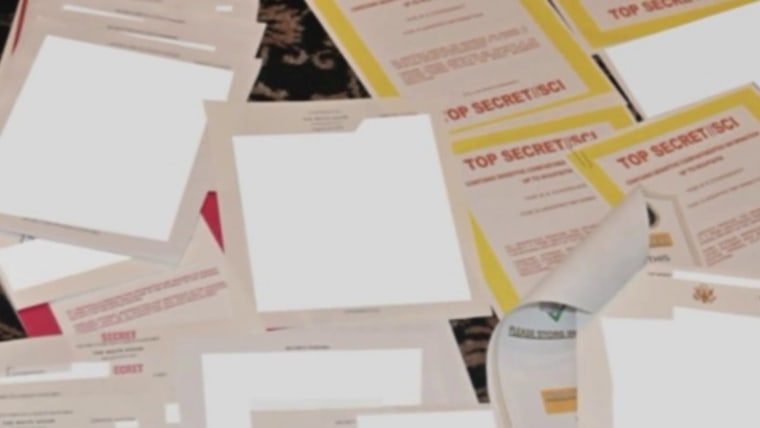

In a major blow for the government, a federal judge approved former President Donald Trump’s request for a special master to oversee all the evidence the FBI seized last month from his Mar-a-Lago estate and temporarily blocked parts of the Justice Department’s investigation. U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon — a Trump appointee — said in her ruling Monday that the special master should be able to review the seized documents both to address questions of attorney-client privilege and to litigate claims of executive privilege.

The idea that executive privilege is even at play in this case is genuinely weird. At issue are documents that belong to the federal government, not to Trump. What’s more, the former president is a private citizen with no executive authority, so he can’t exert power he doesn’t have to hold materials that aren’t his.

Peter Shane, a legal scholar at NYU and a specialist in separation of powers, told The New York Times yesterday, “The opinion seems oblivious to the nature of executive privilege.”

Indeed, given the scope of Cannon’s ruling — extending oddly broad powers to an as-yet-unnamed special master, while simultaneously blocking prosecutors from further examining the seized materials, even while other parts of the government can continue to scrutinize the documents — the response from legal experts was swift and unkind.

Stephen Vladeck, a law professor at University of Texas, called the outcome “preposterous,” adding that yesterday was “a sad day“ for the judiciary. Andrew Weissman, a longtime Justice Department veteran and an MSNBC legal analyst described the ruling as “lawless“ and “nutty.”

Neal Katyal, a former acting solicitor general, described Cannon’s legal analysis as “terrible” and “awful,” before concluding, “Frankly, any of my first year law students would have written a better opinion.”

Ryan Goodman, a New York University law professor, told the Times, “Judge Cannon had a reasonable path she could have taken — to appoint a special master to review documents for attorney-client privilege and allow the criminal investigation to continue otherwise. Instead, she chose a radical path.”

Those who gave the jurist the benefit of the doubt have reason to be disappointed, but perhaps we shouldn’t be too surprised. Cannon has a reputation as a far-right jurist and a Trump-appointed Federalist Society member. What’s more, it was after Election Day 2020 — the point at which voters rejected Trump, during his coup efforts — when Senate Republicans confirmed the young conservative to a lifetime position on the federal bench.

Roy Cohn was known for saying, “Don’t tell me what the law is, tell me who the judge is.” The relevance of that quote lingers for a reason.

Cannon said at the outset that she was inclined to give Team Trump what it wanted, but she thought it best to give the Justice Department an opportunity to make its case.

When prosecutors did exactly that in devastating fashion, the Trump-appointed judge ignored them and issued a ruling legal scholars are hard pressed to defend.

As for what’s next, it’s unclear how and whether the Justice Department might appeal. Complicating matters, of course, is that the matter would next go to the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, where Republican-appointed judges have a sizable majority.