MS NOW OPINION

Understand Today’s News

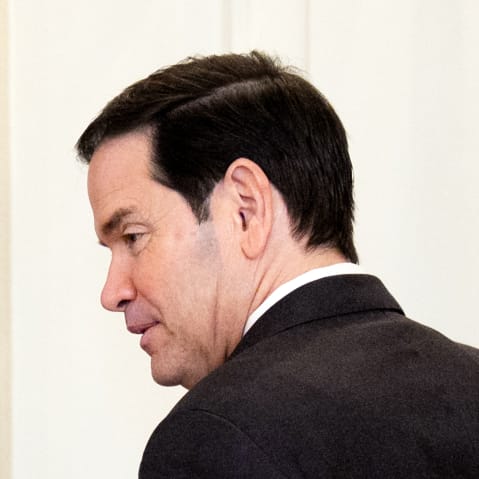

The unsubtle subtext of Gavin Newsom’s ‘culturally normal’ comment

Nicholas Mitchell

Like this content? Follow our rundown delivered daily right to your inbox

Shows

Know Your Value

Latest from MS NOW

Maddowblog

Friday’s Mini-Report, 12.12.25

The Tea Spilled Morning Joe