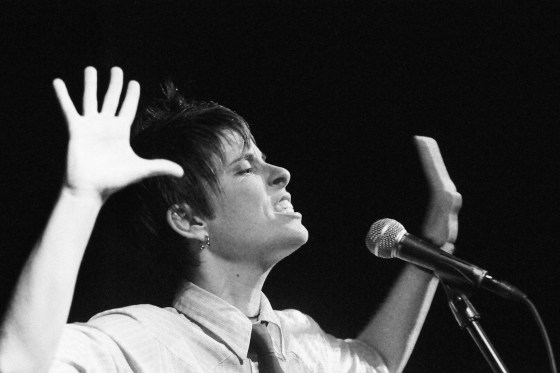

Andrea Gibson, the poet laureate of Colorado and one of America’s best contemporary poets, died on Monday at age 49, after navigating an ovarian cancer diagnosis for the last four years. I phrased the previous sentence carefully. As Gibson said, “Whenever I leave this world … I wouldn’t want anyone to say I lost some battle. I’ll be a winner that day.”

Gibson was an artist and activist, whose spoken word poetry captivated millions and defied the hyperindividualism that defines this political moment. They and their wife, Megan Falley, are the subjects of a forthcoming documentary, “Come See Me in the Good Light,” which won the Festival Favorite Award at the Sundance Film Festival. Gibson recognized that existence itself is a political act — and they honored this by weaving love, hope, divinity and their queerness into everything they did. Their work grappled with the nature of what it is to be alive with precision and clarity, often distilling some of our most complex existential questions — and their answers — into just a few lines: “I said to the sun, ‘Tell me about the Big Bang.’ The sun said, ‘It hurts to become,’” one of their poems goes.

You tap into the brevity of something and all of a sudden, everything becomes more special.”

Andrea Gibson

Gibson’s words were imbued with a spiritual nondualism, which recognized the deeply interconnected nature of existence, both in terms of our connection to one another and the world around us. In pulling back the veil, dissolving the fallacious notion that we are somehow separate from one another, we cannot help but be led by love, their work implores.

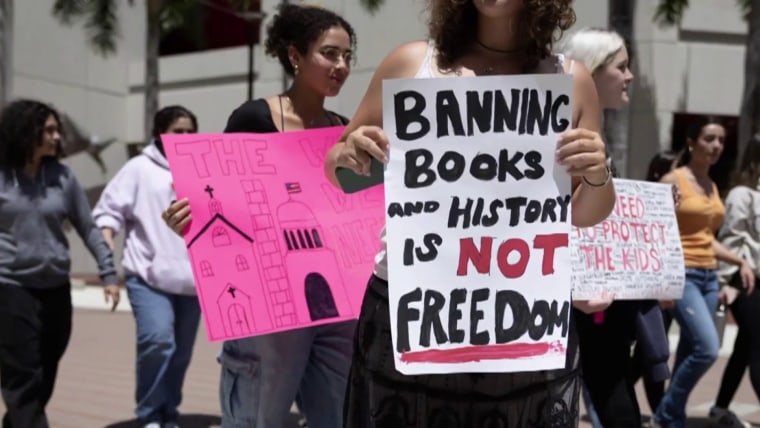

Hyperindividualism, by contrast, is used to legitimize the violence, oppression and betrayal of so many in this country right now. It produces a worldview that excuses mass inequality and convinces those who hoard wealth that, for example, Republicans’ tax cuts for the richest are worth kicking millions off of Medicaid and leaving poor children hungry — policy changes that will literally lead tens of thousands of people to die every year. It convinces those who materially benefit from this brutality that somehow we won’t all suffer.

Gibson and their work, on the other hand, exposed the lie that fuels the violence of this political moment. Implicitly and explicitly, Gibson instead reminded us that another’s pain is our own pain — and so, too, is their joy. What’s more, they offered a way forward amidst the wreckage and fear and heartache. Their work encourages us to acknowledge everything we are grieving while not losing a sense of hope. In the poem “Good Grief,” they write: “Let your / heart break / so your spirit / doesn’t.”

Gibson’s words disclose that once we find the willingness to stop fighting our reality, our mortality, our fears and even ourselves, only then does the infinite stretch out before us. This, they contend, is how we access our own divinity — and the divinity of everything and everyone around us. “You tap into the brevity of something and all of a sudden, everything becomes more special,” they said in an interview about their terminal cancer diagnosis last year. They continued:

That’s why, for a lot of this time, I’ve not necessarily felt that I have less time than anybody else because I’m walking through this world where I’m watching everybody walk by the moment and there is no moment but this one. … I didn’t know how ecstatic the moment is, how full it is, and how expansive it is. There is so much more time in a moment than there is in a decade.

In a letter they wrote to their wife, Falley, entitled “Love Letter From The Afterlife,” Gibson writes:

I wish you could see the beauty your spirit is right now making of your pain, your deep seated fears playing musical chairs, laughing about how real they are not. My love, I want to sing it through the rafters of your bones, Dying is the opposite of leaving. I want to echo it through the corridor of your temples, I am more with you than I ever was before.

Hyperindividualism begets disconnection and brokenness. Gibson showed us that the abundance and connection each moment contains provides us with what we need to stitch together and repair this brokenness and disconnection, which, in turn, will fortify us in our work for freedom. Their work was a continual reminder that to transcend is not to leave this earthly plane: it is to return to, and immerse ourselves in, this moment. “Ask me the altitude of heaven,” they wrote, “and I will answer, ‘How tall are you?’”