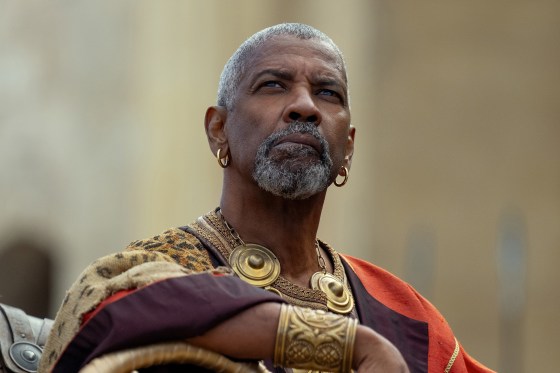

Denzel Washington, who steals the show in "Gladiator II" with his depiction of Macrinus, a gladiator-turned-arms and slave trader with political aspirations, has always been at his best when he’s playing characters who wrestle with moral questions and personal shortcomings. We’ve seen it in movies like “He Got Game” (1998), “Malcolm X” (1992), “The Hurricane” (1999) and “Fences” (2016). He won the Oscar for best actor for playing the equally righteous and sadistic LAPD Detective Alonzo Harris in “Training Day” (2001). Throughout a career spanning 50 movies, Washington shines in roles like Macrinus, in which he makes it hard for viewers to figure out whether he’s a “good guy” we’re supposed to be cheering or a “bad guy” we’re supposed to condemn.

Washington shines in roles like Macrinus, in which he makes it hard for viewers to figure out whether he’s a “good guy” we’re supposed to be cheering or a “bad guy” we’re supposed to condemn.

Perhaps he’s drawn to these roles because he knows that when he was growing up in Mount Vernon, New York, it would have been hard for people who saw him to figure out whether he was a “good guy” or “bad guy,” a “hero” or a “villain.” Washington describes for Ryan D’Agostino at Esquire a story of his life that includes sweet boyhood experiences like playing live music with friends, mimicking the walks of older neighborhood boys and excitedly watching the construction of a Boys Club (now a Boys & Girls Club) and then joining it. But there are darker moments, too, like running for shelter when a friend’s brother is about to commit a murder and Washington’s dealing drugs and shooting up himself.

Despite testing well in school, Washington tells D’Agostino, “I had one foot in the streets. I can’t remember if I was already selling drugs at that point. (Yeahhh, well ... sometimes you do what you’re around.)” Then, referring to his friends who would eventually serve decades in prison, Washington says: “I was doing everything Frank and Mitch were doing. Throwing rocks at the penitentiary, as they call it. I was throwing rocks at the penitentiary at thirteen. I stopped going to school much, so they sat down with my mother, said, Look, you need to get him out. Said I showed ‘potential.’”

Washington’s first-person account of his childhood is reminiscent of James Baldwin’s “Letter From a Region of My Mind,” in which he describes fearing a future life of crime that he could see more clearly than any other.

Things could have spiraled for Washington like they did for his closest friends if his mother hadn’t sent him away to what he calls “a little private, semi-military school” in upstate New York. One of the biggest takeaways from Washington’s interview is that there is more to him than meets the eye. He plays heroes but insists he isn’t one. It follows, then, that he can play bad guys convincingly but he’s not a bad guy — even if he’s done things that would get him labeled as bad throughout his life.

As Macrinus, Washington delivers his lines and flashes that smile as only he can, playing a character who we know from the beginning is sketchy. But Macrinus’ disdain for the bloodthirsty regime that held him as a slave is somewhat noble. In portraying the villain with redeeming qualities, Washington blurs the line between what counts as virtue and what counts as vice. Again, Washington excels at portraying these sorts of characters who cannot be painted with too broad a stroke, ones who are basically honorable but fall short or ones who are mostly bad but show flashes of heroism. “Even in the darkest stories,” he told the magazine, “I’m looking for the light.”

One lesson from “Gladiator II” is that when faced with grim circumstances or immense threat, many of us might find our morals lacking.

The writer Reginald Dwayne Betts has argued that his life — and, indeed, nobody’s life — should be reduced to his criminal record and incarceration. We can see that Washington feels the same way in the way he talks about his boyhood friends and associates. However long and menacing their rap sheets, their brushes with the law still tell only partial stories about who they are. One lesson from “Gladiator II” is that when faced with grim circumstances or immense threat, or when filled with vengeful rage or tempted by great wealth or power, many of us might find our morals lacking.

“I was in Mount Vernon not long ago and I ran into Frank,” Washington tells the magazine. “No kidding. Somebody yelled over to me, ‘Yo, D, you know Frank lives right here?’ Look, I got a picture of the two of us—we’re the same age but it doesn’t look like it. Look at that broken body of his. ... I always take care of Frank. He knows when he sees me, I hit him off. He didn’t have a chance, man.” Washington recognizes that despite getting “into armed robbery and all kinds of stuff,” Frank served his time and is as deserving of friendship and care as anyone else.

Frank, who Washington says didn't have a mother or father and was staying with another friend, didn’t have much of a chance, but Washington did. He found his way to acting through the Boys Club and eventually threw himself into the craft at Fordham University. Even as his career took off, he explains, he was at times consumed with bitterness, drinking too much and not always present at home.

That’s not the Denzel Washington his fans have imagined him to be, but it is the Denzel Washington whose internal complexities and vices have allowed him to breathe life into the characters we love.