U.S. District Court Judge Stephanie Gallagher asked a pointed question of the Trump administration on Tuesday. Last month, she had ordered the government to work to facilitate the return of a 20-year-old Venezuelan national who had been mistakenly removed to El Salvador’s Terrorism Confinement Center, or CECOT. According to a U.N. document filed Monday in a case related to one before her, the deportees in CECOT weren’t beyond reach, as the DOJ had claimed in her courtroom. Instead, according to the government of El Salvador, the men in the maximum-security prison have been apparently there under U.S. jurisdiction all along.

In a letter to the Justice Department, the Maryland federal judge asked exactly who has been lying: the Salvadoran government to the United Nations or the government’s lawyers to her. The answer is most likely the latter as the idea that El Salvador is the dominant player in this farce is laughable at best — but let’s unpack why the lie was ever needed.

The Maryland federal judge asked exactly who has been lying: the Salvadoran government to the United Nations or the government’s lawyers to her.

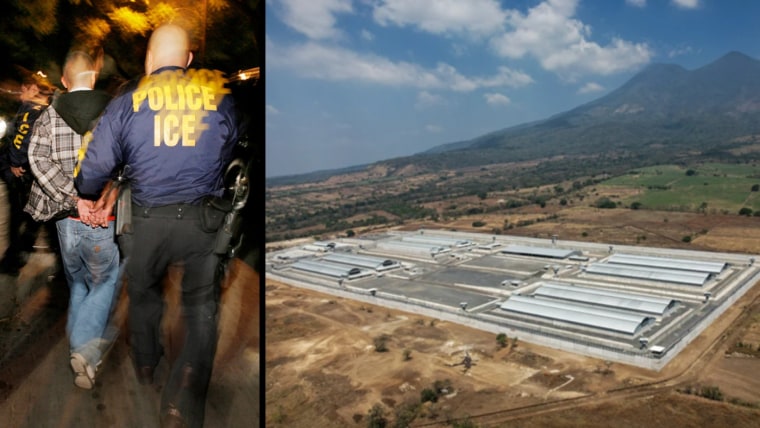

As part of his broader mass deportation scheme, President Donald Trump has been busy pulling all possible levers to test how quickly immigrants can be jettisoned from the country. In March, he invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, a law previously only invoked during wartime, to claim that the U.S. is facing an invasion from a Venezuelan gang known as Tren de Aragua. Immigration agents swiftly rounded up hundreds of people it claimed were violent gang members and shipped them off to CECOT without any semblance of due process.

When U.S. District Judge James Boasberg ordered the administration to pause the deportation of a group challenging their removal under the act and turn around any planes that might have already taken off, the administration simply ignored the order. White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt incredibly claimed that because some of the planes were already outside U.S. airspace that they were beyond the court’s reach.

The administration would later argue that once the men were in Salvadoran custody, the matter was largely out of its hands. “DHS does not have authority to forcibly extract an alien from the domestic custody of a foreign sovereign nation,” Joseph Mazzara, acting general counsel at the Department of Homeland Security, wrote in a court filing in April. In the separate case of Kilmar Abrego Garcia, who the administration admitted it had wrongly deported, Attorney General Pam Bondi said: “That’s up to El Salvador if they want to return him. That’s not up to us.” And a senior State Department official, Michael Kozak, said in a sworn declaration filed to Boasberg in May that “the detention and ultimate disposition of those detained in CECOT and other Salvadoran detention facilities are matters within the legal authority of El Salvador in accordance with its domestic and international legal obligations.”

That’s all in line with what El Salvador President Nayib Bukele told Trump during an April visit to the White House. But it’s not what his government told a U.N. inquiry investigating the involuntary disappearances of four Venezuelans. According to the U.N. Working Group’s report, El Salvador’s authorities were emphatic that they had not arrested or detained any of the men in question:

The actions of the State of El Salvador have been limited to the implementation of a bilateral cooperation mechanism with another State, through which it has facilitated the use of the Salvadoran prison infrastructure for the custody of persons detained within the scope of the justice system and law enforcement of that other State. In this context, the jurisdiction and legal responsibility for these persons lie exclusively with the competent foreign authorities, by virtue of international agreements signed and in accordance with the principles of sovereignty and international cooperation in criminal matters.

Translation: these are the U.S.’ prisoners being held in CECOT, and we’re just holding them in line with a bilateral deal that we made.

The lawyers representing the deported Venezuelans filed the U.N. report with Boasberg on Monday, highlighting to the judge that it clashed with the administration’s claims of helplessness. Their filing also caught the eye of Gallagher. In her letter, she asked the government to explain why the State Department would need to enter "diplomatic discussions" with El Salvador regarding the CECOT detainees, when the country apparently "has no sovereign interest" in holding the man whose return she'd ordered.

The dance around responsibility further underscores the real utility of places like CECOT for authoritarian regimes.

The dance around responsibility further underscores the real utility of places like CECOT for authoritarian regimes. The megaprison serves as a kind of liminal space for legality, a place where domestic laws don’t apply as readily and abuses can run rampant. In practice, Trump’s actions are not dissimilar to the George W. Bush administration’s extraordinary renditions of terrorism suspects to CIA-operated black sites in Romania and Lithuania or the use of Guantanamo Bay to keep “militant combatant” detainees out of Article III courts. But then, as now, the detainees held at CECOT are in America’s “constructive custody,” if not physical custody, which means that the right of due process is available to them.

It was always going to be hard to maintain the fiction that El Salvador is the final arbiter of the fate of detainees held in CECOT’s Module 8. The client-service provider relationship that Trump and Bukele have fostered reportedly amounts to the U.S. paying several million dollars to El Salvador to hold criminal detainees for a year. (The Trump administration also returned top MS-13 gang leaders, undercutting federal investigations into a deal between Bukele’s government and the notorious cartel.) The arrangement, which Bukele was reportedly nervous about executing, has always made the claim of powerlessness from the U.S. seem tenuous at best, but the U.N. Working Group’s report demolishes it entirely.

All of which brings us back to Gallagher’s initial question, which she gave the administration until next week to answer. By shipping detainees to a place where the administration claims American laws don’t apply, the hope was clearly to treat the detainees as the pebble dashing back and forth in a shell game. But with their admission to the U.N., the Salvadorans have upended the whole table, exposing the charade for all to see.