Ed Martin may have finally found his calling: He will lead a made-up sounding organization to investigate imagined abuses of power.

But while Martin’s new job may feel fake, the dangers posed by it are very real.

After flaming out as President Donald Trump’s nominee for U.S. attorney in the District of Columbia, Martin has been resurrected in a role where he can perhaps do even more damage, as head of the Justice Department’s “Weaponization Working Group.”

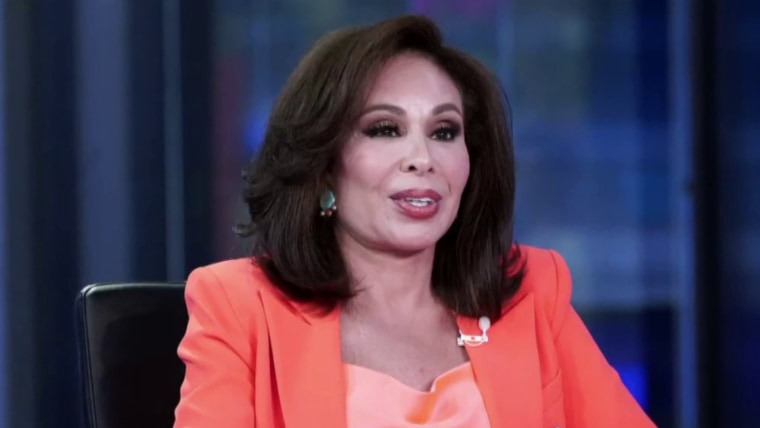

Attorney General Pam Bondi created the group in February, declaring her intention to restore the ‘integrity and credibility’ of the DOJ.

Attorney General Pam Bondi created the group in February, declaring her intention to restore the “integrity and credibility” of the DOJ. Bondi’s memo goes on to accuse other prosecutors of abusing their power “to achieve political objectives,” listing Jack Smith, Alvin Bragg and Letitia James as examples. All three, of course, have initiated criminal or civil cases against Trump.

A jury found against Trump in the case led by Bragg and a judge found against Trump in the case led by James. The cases brought by Smith never made it to a jury trial, but grand juries returned indictments after finding probable cause that Trump unlawfully retained national defense information and interfered in the 2020 presidential election. There is no evidence that these cases were brought to achieve purely political objectives.

In an introductory press conference, Martin made an extraordinary pledge: to share disparaging information about former government officials even if the evidence is insufficient to support criminal charges against them. According to Martin, “if they can’t be charged, we will name them … and in a culture that respects shame, they should be people that are ashamed. And that’s a fact. That’s the way things work. And so that’s, that’s how I believe the job operates.”

If Martin really does follow through on that de facto mission statement, it will be a betrayal of both DOJ policy and legal ethics, which prohibit prosecutors from making extrajudicial statements about individuals under investigation. Moreover, while “name and shame” is a tactic that the DOJ uses in certain circumstances, Martin’s description is not how that strategy works, either. “Name and shame” in a DOJ context refers to the practice of filing a detailed indictment against defendants who cannot be arrested because they are in a country from which they cannot be extradited.

This technique fulfills a legitimate law enforcement interest by exposing alleged misconduct as a deterrent. For example, five Chinese military hackers were named in a 2014 indictment accusing them of economic espionage in the steel industry to expose the activities of a hostile foreign adversary. In 2016, 13 Russian intelligence operatives were named in special counsel Robert Mueller’s indictment accusing them of interfering with the 2016 presidential election.

But importantly, this strategy is generally only deployed after a grand jury finds evidence sufficient to establish probable cause and returns an indictment. Martin, on the other hand, suggests he will publish disparaging information about individuals even in the absence of such evidence, a breathtaking breach of DOJ norms.

As a federal prosecutor, I learned quickly that the DOJ takes its obligation to refrain from making statements that could harm a person’s reputation seriously. Or at least, it used to.

The ‘Justice Manual,’ the DOJ’s policy guidebook, prohibits personnel from confirming or denying even the existence of an investigation.

When I first became a U.S. attorney, my colleagues and I were sent to the Justice Department training center in Columbia, South Carolina, to learn the do’s and don’ts of making public comments about our work. We were taught we must avoid making statements outside of the public record except where required, such as an active crime spree in which public safety is at risk. The “Justice Manual,” the DOJ’s policy guidebook, prohibits personnel from confirming or denying even the existence of an investigation, lest they cast aspersions on the subject of the probe.

In addition to DOJ policy, ethics rules also prohibit prosecutors from making statements that could harm the reputation of a person under investigation. Rule 3.8(f) of the Model Rules of Professional Conduct, a provision describing the special responsibilities of prosecutors, prohibits lawyers for the government from making “extrajudicial comments that have a substantial likelihood of heightening public condemnation of the accused.”

Recall that the justification for firing then-FBI Director James Comey during Trump’s first term was his 2016 press conference regarding Hillary Clinton’s private email server. While Comey publicly recommended against filing charges, he nonetheless castigated the presidential candidate for conduct he called “extremely careless.”

In a memo supporting Comey’s termination, then-Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein wrote that Comey ignored a “longstanding principle: we do not hold press conferences to release derogatory information about the subject of a declined criminal investigation. Derogatory information sometimes is disclosed in the course of criminal investigations and prosecutions, but we never release it gratuitously. The Director laid out his version of the facts for the news media as if it were a closing argument, but without a trial. It is a textbook example of what federal prosecutors and agents are taught not to do.”

Martin, however, has apparently never read the textbook. In January, Trump appointed him interim leader of the nation’s largest U.S. attorney’s office despite a complete lack of prosecutorial experience. Martin had previously served as the chairman of the Missouri Republican Party, president of Phyllis Schlafly’s Eagle Forum and a lawyer in private practice.

Perhaps not surprisingly, as interim U.S. attorney, Martin acted more like a Trump attack dog than an evenhanded administrator of justice. He fired and investigated career prosecutors who had worked on cases regarding the Jan. 6 attack. He dismissed pending cases against Jan. 6 defendants, including one he had previously represented. As part of what he called “Operation Whirlwind,” he sent letters to Democratic politicians demanding answers about their public statements, to the Georgetown University Law Center questioning its teaching and hiring policies, and to medical journals inquiring into their content, creating a climate of intimidation and potentially chilling free speech.

Unlike the U.S. attorney position, Martin’s new role does not require Senate confirmation. But it will still allow Martin to carry Trump’s water by publicly accusing his accusers of misconduct, even in the absence of evidence that any crime was committed. This is terrible news for prosecutors who have worked on any number of cases Trump may find personally objectionable.

The immediate harm will be to the reputation of the public servants who worked long hours to uncover evidence of Trump’s alleged wrongdoing. The long-term damage will be to discourage honorable people from joining the Justice Department for fear that they might end up in the crosshairs of a hostile future administration. And meanwhile the public will lose its protection from corruption at the highest levels of government.