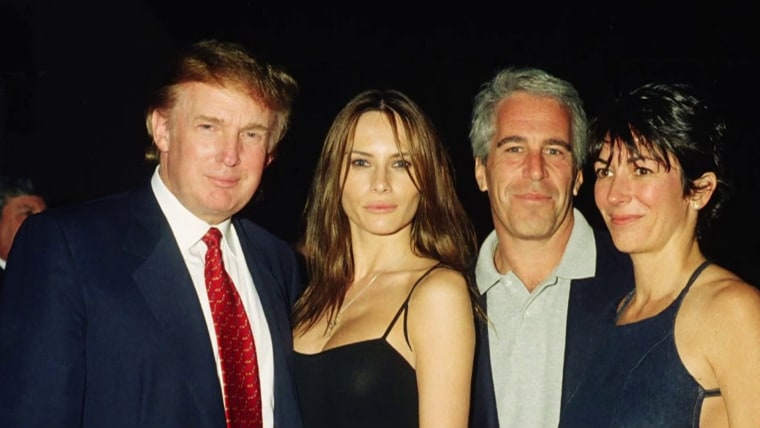

One of the biggest questions people were asking after Department of Justice officials met with Ghislaine Maxwell in a Florida courthouse late last week was: What did the DOJ plan on asking Jeffrey Epstein’s former alleged enabler, who’s now serving a 20-year federal sentence for sex trafficking?

Another big question: What are a convicted sex trafficker like Maxwell’s answers worth?

What are a convicted sex trafficker like Maxwell’s answers worth?

Maxwell might have information that is devastating to the president, or no information about the president at all. And it could be that the government’s interest in speaking with Maxwell is purely for the pursuit of justice and does not pertain to the president’s personal self-interest.

Perhaps an even bigger question here: What does the government have to offer Maxwell in return if it is seeking her cooperation?

The most obvious answer is her freedom, which could come in the form of a presidential pardon. When asked about issuing a pardon or clemency to Maxwell, Trump on Friday told reporters: “I’m allowed to do it, but it’s something I have not thought about.” For Maxwell’s part, her attorney said in response to Trump’s comments: “We haven’t spoken to the president — or anybody — about a pardon,” but added, “we hope he exercises that power in a right and just way.”

The pardon power is arguably the broadest power granted to the president by the Constitution. Indeed, it knows few strictures. And that was before the Supreme Court’s 2024 presidential immunity decision. The court’s decision in Trump v. United States held that a former president has absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for core official acts, presumptive immunity for other official acts, and no immunity for private or unofficial conduct. The pardon power unquestionably falls into the first category: It’s a core official act.

As law professor Kim Wehle pointed out some time ago, when the Supreme Court’s immunity decision was before the court on oral argument, the parties seemed to agree that the pardon power “unlike virtually any other provision of the Constitution, cannot be reasonably construed as limited or constrained in any way, for any reason — even if used corruptly or to facilitate the commission of a crime.” Justice Sonia Sotomayor answered the question even more directly in her dissent: “Takes a bribe in exchange for a pardon? Immune. Immune, immune, immune.”

On the one hand, this kind of meeting — with prosecutors seeking information from a criminal in exchange for some leniency — goes on all the time. Government prosecutors routinely enter into cooperation agreements with criminals, including criminals who are liars — often convicted liars. In trials, prosecutors will own this. They will say in their closing arguments to a jury at trial something to the effect of, “We didn’t choose this witness; the defendant chose this witness.” Or, “Liars hang out with other liars; they don’t hang out with honest people.” Cooperating witnesses, or “cooperators,” testify favorably for prosecutors in return for leniency in their own cases.

The problem is, as defense attorneys see it, someone sitting in federal prison for 20 years might have an incentive to say anything they have to say to get out of prison. The DOJ knows there are risks in relying on dishonest criminals for information. But there’s the reasoning that it’s criminals who know what the other criminals do. Additionally, juries seem to accept that cooperating witnesses are flawed people. (Isn’t everyone? Well, maybe not like this.)

It’s likely Maxwell is too radioactive to Trump. The president has shown he likes to pardon people who will get him good press, not bad press.

So, might Maxwell’s attorneys have similarly demanded leniency — in the form of a pardon or clemency from the president, for example? It would certainly be good advocacy to make the request. Indeed, a senior administration official, who spoke to NBC News on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak publicly, said that Maxwell was granted limited immunity by the Justice Department to answer questions about the Epstein case, without risk of additional prosecution.

And Maxwell’s attorneys could, in theory, ask for a pardon in direct exchange for their client’s testimony, should Trump’s DOJ determine her testimony is sufficiently valuable whether for the pursuit of justice or Trump’s self-interest.

If Trump is already confident there’s nothing in the Epstein files that can damage him, as he has claimed, then Maxwell’s information might just not be that valuable to him.

But most important, it’s likely Maxwell is too radioactive to Trump. The president has shown he likes to pardon people who will get him good press, not bad press. He’s trying to distance himself from Epstein — not cozy up to the one person who may have been convicted in Epstein’s stead. And Trump doesn’t really dispense pardons that liberally. Ten years ago, he could have avoided making an enemy out of his then-trusted confidant and lawyer Michael Cohen when Cohen was charged by federal prosecutors (it remains a mystery why he didn’t do so). Cohen has been a thorn in Trump’s side ever since.

The Jan. 6 pardons were mass pardons, but that doesn’t mean they were scattershot or haphazard. (In fact, there’s plenty of precedent for mass pardons. President Jimmy Carter pardoned everyone who dodged the Vietnam War draft. President George Washington pardoned the participants in the Whiskey Rebellion.) Importantly, those Jan. 6 defendants were all Trump’s base, so he presumably got a lot in return, politically, from that decision.

For all of American history, there was nothing wrong with a president pardoning someone when it served his interests. The Framers, though they were obsessed with preventing corruption, deliberately chose to vest the vast pardon power in the executive. It was a matter of debate, and some of the Framers didn’t want to include it. It’s part of the English (royal) tradition; but it’s also not essential to our working government.

Self-interested pardons have always been a hallmark of presidential pardons, though not those processed by the Office of the Pardon Attorney. Bill Clinton pardoned his brother and a billionaire financier whose ex-wife donated heavily to the Clinton Library and Hillary Clinton’s Senate campaign.

It’s just that now, after the Supreme Court immunity decision, the president can probably openly sell pardons if he wants to. Let’s hope Trump doesn’t want to sell one to Maxwell. Even if he is in fact “allowed to do it.”