On Friday, Judge Arthur Engoron ruled that former president Donald Trump, the Trump Organization, his former CFO and his adult sons have to pay more than $350 million in penalties. Engoron also barred the former president “from serving as an officer or director of any New York corporation or other legal entity in New York for a period of three years.” The ruling, though likely to be appealed, marks another defeat for Trump in a civil case. And those losses are powerful predictors of what’s likely coming once his criminal trials commence.

Trump fights every battle, large and small, in the court of public opinion. That court has no rules of engagement, no rules of evidence and no rules of procedure. There are no attorneys to object and no judges to tell Trump to sit down and cease disrupting the proceedings. There are no constitutional constraints. So, during his campaign rallies, his hallway outbursts outside courtrooms and his interviews with media outlets, Trump can lie, largely with impunity.

When the rules of evidence and procedure apply to legal contests, Trump loses.

But when his legal disputes move into courts of law, he loses. When the rules of evidence and procedure apply to legal contests, Trump loses.

Let’s briefly recap his last three civil trials. As is his right in a civil case, Donald Trump opted not to attend the first trial, regarding E. Jean Carroll’s allegation that he raped her in a Manhattan department store in the 1990s. His attorney in that case, Joe Tacopina, was bound by the rules of evidence and procedure, and Trump lost. Though in public he claimed — and still claims — he never met Carroll, the jury ruled unanimously that he had sexually abused and defamed her, and awarded Carroll $5 million.

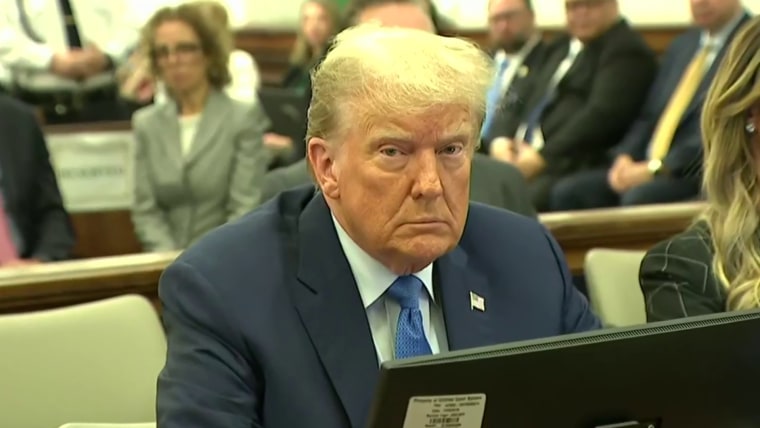

In the second trial involving Carroll, which solely concerned her claim that Trump defamed her, the former president decided to attend, at least sporadically. Yet events turned out even worse for him. The jury saw him mumble under his breath, glower at witnesses and even storm out of the courtroom during closing arguments, as Carroll’s lawyer was telling the jury that Trump seems to believe that the rules don’t apply to him. Still, his lawyer, Alina Habba, was required to follow the rules of evidence and procedure (even she seemed poorly versed in those rules). Trump lost again, and this time the jury awarded Carroll $83.3 million.

In his New York business fraud trial, Trump frequently attended court, but was defeated just as frequently. In public, Trump has insisted he never overstated the value of his properties, yet Judge Engoron found that the documentary evidence of fraud was so overwhelming that even before trial, he ruled that Trump, his sons and the Trump Organization’s chief financial officer had fraudulently inflated asset values.

During breaks in the proceedings, the former president would emerge from the courtroom to spew more lies about the case to media cameras. But inside the courtroom, where cameras were not allowed, Trump’s legal team was required to follow the rules, and Trump again lost.

This string of civil trial losses augurs poorly for the former president’s coming criminal trials. First, unlike civil trials, defendants are required to attend all trial proceedings in criminal cases. Given that his “best” result (being ordered to pay “only” $5 million) came in a trial Trump ghosted, it’s hard to see how his daily attendance at the criminal trials would work to his advantage.

As we have seen in the civil trials and related depositions, Trump would not make a particularly good witness in his own defense.

Furthermore, as a general proposition, criminal trials are more exacting affairs than civil cases. The rules of criminal procedure and the rules of evidence must be strictly observed by attorneys and judges alike.

How would the rules of evidence deal with, for example, Trump’s claim that he took the classified documents from the White House upon leaving the presidency because he believed the Presidential Records Act authorized him to do so? Recall that, in the court of public opinion, Trump has endlessly claimed that he could declassify documents just by thinking about it, and that the PRA lets him do what he likes with those classified documents he ferreted away to Mar-a-Lago.

In a federal criminal trial, one of the most important rules of evidence is the rule that governs “statements of a party opponent.” In layman’s terms, that rule says a prosecutor can introduce into evidence any statement made by a defendant if the prosecutor believes it is incriminating or will otherwise prove some point that helps build the case against him. But the rules against hearsay prohibit a defendant from introducing his own out-of-court statements into evidence.

These rules make special counsel Jack Smith’s job easier and Trump’s defense harder. In the classified documents trial, for example, Smith will need to prove that Trump knowingly took and retained the documents when he left the White House. Because Trump has said many times that he “took” the documents, those out-of-court statements can be introduced into evidence by Smith to prove Trump knowingly took the documents.

But what if Trump wants to defend himself by arguing that he believed he could take the documents under the PRA, trying to give himself a defense that he either was entitled to take the records or that he lacked criminal intent? All those statements are inadmissible under the rules of evidence if the defendant tries to introduce them.

The only way Trump’s lawyers could introduce Trump’s beliefs is if Donald Trump takes the stand and testifies. As we have seen in the civil trials and related depositions, Trump would not make a particularly good witness in his own defense. Indeed, when Trump testified in the second E. Jean Carroll trial, he was on the stand for less than five minutes and the jury ordered him to pay Carroll $83.3 million. It’s hard to see how his testimony helped him.

The same dilemma faces Trump in the 2020 election interference case. The public record is replete with statements from the former president that Smith can use against him in trial. But if Trump’s lawyers want to prove he genuinely believed the election was stolen or rigged, out-of-court statements will not be allowed as evidence.

For years, there has been a persistent belief that Trump is somehow immune to the consequences of his behavior. His political record — including a rare defeat for an incumbent president — is in fact mixed at best. In court, the record is even clearer. Once Trump is constrained by the rules of evidence and the rules of criminal procedure — no longer allowed to say what he wants about stolen elections and telepathically declassifying documents — his series of trial losses is very likely to continue.