Voters in battleground states, especially those that will dictate control of the Senate, have probably heard a lot of specific numbers in recent months. There’s the number of jobs created, the inflation rate, the number of Americans who are losing their reproductive rights, the number of votes parties need on Capitol Hill to claim majorities, and the made-up number of IRS agents who’ll soon enforce tax laws.

But as Election Day nears, there’s another number to keep in mind: six.

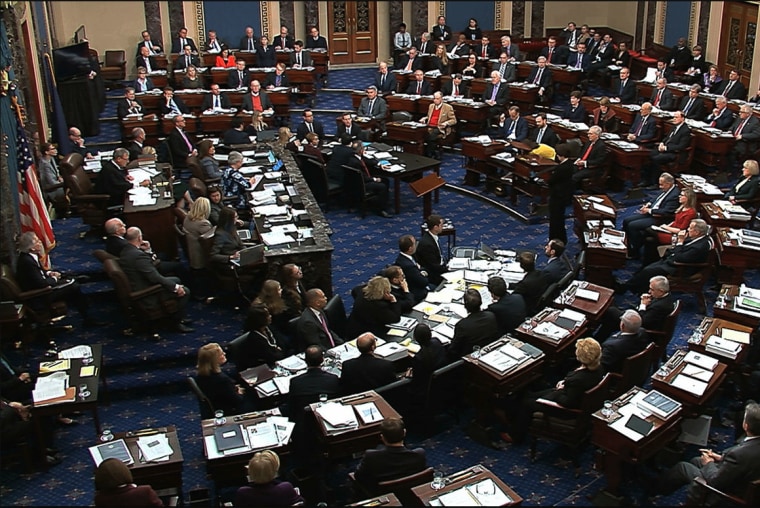

That’s the number of years in a U.S. senator’s term after winning a general election.

In U.S. House races, voters can take some comfort in knowing that if they make an unwise choice in one election cycle, they can correct their mistakes relatively soon thereafter. The day House members take the oath of office, they know their re-election campaigns are the following year, and some will face primary races in roughly 15 months.

When voters take a chance in a Senate race — on candidates with dubious records and/or questionable qualifications — and they come to realize that they made a poor choice, they’ll have to live with that decision for quite a while.

In fact, this year is unusual in that there’s a large number of first-time Senate candidates who’ve never held elected office and who have little to no background in public service of any kind. In nearly every instance, these candidates are running against more experienced opponents — with records that are easy to assess — whom voters already know.

These first-time candidates are effectively asking the electorate to take a chance on them, trusting that they’ll do well in the Senate, despite their inexperience and suspect skills. Some are favored to win.

And who knows, maybe these first-time candidates will excel, impress their constituents, and become Capitol Hill giants. Maybe voters will gamble on these problematic candidates and the experiment will work beautifully.

But there's another possibility. Perhaps these candidates — some of whom don’t appear to know or care about governing or even the basics of policymaking — will prove to be embarrassing, not just to themselves, but also to their states, their parties, and their constituents.

If so, voters will have an opportunity to elect someone else at the end of these senators’ terms, but therein lies the point: Members elected this year won’t face the electorate again until 2028. Senators who end up humiliating themselves will have their powerful jobs for six long years — and there won’t be anything their embarrassed constituents can do about it.